For more than five decades, the photographs, music videos and films of Anton Corbijn have enthralled audiences around the world. The Dutch master is arguably best known for his long-term creative associations with rock behemoths U2 and Depeche Mode, but his body of work is significantly more than that. He has directed five feature films with the latest, Switzerland starring Helen Mirren, set for release in 2026.

Born in May 1955, Corbijn is the son of a parson (after whom he is named) in the Dutch Reformed Church, and spent the first 11 years of his life on the small island of Strijen in his native Netherlands. In 1979, aged 24, he took a chance on moving to London, and soon secured his first front cover for music paper NME.

This led to an ongoing relationship with the music industry that blossomed into directing music videos, shooting album covers and creating live sets for Depeche Mode. In 2007, music also featured heavily in his debut feature film, Control, which told the story of Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis.

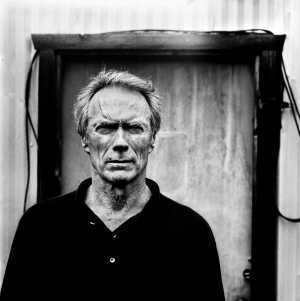

During his career he has photographed rock stars, politicians, models, painters and actors, including David Bowie, Nelson Mandela, Ai Weiwei, the Rolling Stones, Clint Eastwood and hundreds of others.

We caught up with him in his Amsterdam offices, ostensibly to chat about his impressive new 560-page photographic tome, Corbijn, Anton. Despite starting his eighth decade on Earth, he’s a man full of energy, charmingly self-deprecating, and a natural raconteur, with his heavy Dutch accent still intact.

Square Mile: In your new book, you say of photography, “It found me.” Can you explain that statement?

Anton Corbijn: I really wanted to somehow be part of the music world. I lived on an island when I was young and it was like the ‘promised land’ across the water from the island. It seemed to be where everything was nicer, better and more fun than in the very Protestant environment I grew up in. So, that was my focus – and I thought maybe I’d try to learn an instrument or something to be part of that [music] world.

We moved from that island when I was 11, and I first started looking in record shops. When I was 17, we moved to a city, Groningen, in the north of Holland during the school holidays, and I didn’t know anybody yet. I was so shy that I thought I’d borrow my father’s camera [for a gig] and that would give me a reason to go to the front. People will think, “Oh, he has a camera; he must walk to the front.”

When you’re shy, you quite often think that people look at and talk about you, and it makes you very aware of that. It was just a local thing; nothing big. It was a band called Solution and they were on Elton John’s Rocket label. I took a few pictures – nine in total – and sent them to a magazine and they published a few. I was nothing to photography. I didn’t think that was a way into that [music] world, apart from that particular afternoon, which allowed me to walk to the stage. I guess you could say that photography found me that way.

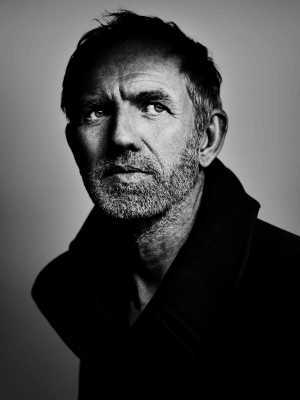

Anton Corbijn

Stephan Vanfleteren

SM: Have any other photographers inspired your work?

AC: I really liked the work of Jim Marshall, Elliott Landy, David Gahr and also the English guy who did the Stones and The Beatles who committed suicide in 1971 – Michael Cooper. They were great photographers, and they mainly stuck to music, although Jim Marshall’s estate finally posted a lot of pictures that are outside that realm. I really thought he was fantastic.

Initially, I didn’t know anything about photography, so I just looked at music photographers. I got to know all of them apart from Michael Cooper, because he passed away prior to me touching a camera. There were those [inspirations] and then [the documentary photographers] Diane Arbus, Robert Frank; I started to like all of that too.

Documentary photography was quite big in Holland in the early 1970s when you had all these revolutions in South America. Photographers were always there and their pictures were published in the weekly magazines in Holland that were sort of left-leaning. There was some great photography, so that was a big influence on me. Maybe not consciously, but, I think looking at the way I photograph, the influence is definitely there.

SM: Then you decided to go to England in the late 1970s?

AC: Yeah, in 1979. If I hadn’t done that, things would have looked very different for me. It was a good decision, but it was slightly out of desperation because I didn’t know what else to do. By then I felt I’d photographed all of the Dutch bands and I was ambitious enough to try it, but it also meant that I’d ‘burnt all my ships’ in Holland, and I couldn’t go back.

There was no safety net and I had to really work at it, but I was lucky that I came at a time that people were open to that kind of photography. I had very little spending money, so I survived with small jobs.

Clint Eastwood, Hollywood, 1997

SM: Then you got more involved with the New Musical Express (NME)?

AC: I moved to London in the last week of October 1979. I loved the NME. In the summer of that year, 1979, I went to see NME editor Neil Spencer to show him some of my pictures I’d done of Elvis Costello, Johnny Rotten, and all that. He loved them and said, “Can we publish some of those?”

They published them over the months and I asked, “If I come to England, would you give me some work?” He said, “Of course.” Then I knocked on the NME door again in November and he didn’t know who I was. I said, “You said you’d give me some work.” It was a big move for me and I had this bloody holiday let in a cellar in Bayswater.

Neil Spencer took me round the offices. It was very chaotic compared to the Dutch music magazines, which were all very neat. All these people were typing he said, “This is Anton; he’s from Holland and he’s a great photographer. Anybody got some work?”

All the typing stopped; they looked over the books they had on their desks and slowly somebody started to type again. One guy started to sing, ‘I hate the fucking Dutch’. That was my welcome at NME in very much NME-style. But it worked out, so I was happy.

SM: In your new book, U2’s Adam Clayton writes about you asking the band to be involved in the process of “making a photograph”. That must involve you building trust with bands and musicians?

AC: In the beginning, nobody knew my work, so I had to prove myself every time. After a while, especially when you photograph the same people – as is the case with U2 – there is a trust.

That helps when you don’t have to reintroduce yourself all the time and they sometimes will take [pose for] pictures that they wouldn’t necessarily do with other people, because they’ll probably do something that makes it look cool, rather than awkward.

But, at the same time, if you’re too familiar, you sometimes don’t push enough. I’m very aware of that and you need to keep pushing. If you make your friends feel uncomfortable, it’s difficult.

U2, Austin, Texas, 1982

SM: A lot of your work is shot outdoors. Do you prefer to work that way?

AC: Absolutely. I don’t like a studio environment and I think you can use an environment to say a lot about the people. Sometimes it’s something to play with and you don’t shoot the same picture all the time, as I think you tend to do in studios. I guess that outdoors is also, for me, about documentary photography – it’s more like that, more often outdoors than indoors.

SM: The music videos started with a German band in the early 1980s, right?

AC: Yeah, with Palais Schaumburg. I did their photographs and album sleeve and they said, “These days we also need a music video. Can you do that too?” That’s how I got into that. I’m not saying I did a great job – I don’t think I did – but it caught the eye of [ZTT Records co-founder] Paul Morley. He then asked me to do something for Art of Noise with Trevor Horn’s old video camera. That was a bit wild. Then I did ‘Dr Mabuse’ for Propaganda, and making that video was more serious.

SM: Had you taught yourself to shoot with video cameras?

AC: Well, it was only with Trevor Horn’s camera that I shot myself. With Dr Mabuse I had a DP [Director of Photography] and I kept having a DP till 1986 when I did my first video (‘A Question of Time’) for Depeche Mode – there was no money for a DP so I did it myself. Then my videos started to ‘move’ a little bit more. Before that it was very much stills [in a video].

SM: Was the new book your idea or were you approached to do it?

AC: I had some exhibitions; starting in Stockholm and it was the idea of a catalogue. Then it coincided with my 70th [birthday], so it became a ‘70th Yearbook’ and a bit bigger than I anticipated.

John Lydon, London 1979

SM: What was the start-to-finish timescale for the book?

AC: I started in the summer of 2024 – but I’d already begun working on my movie (Switzerland) by this point, so I had very little time. I forgot to thank a lot of people in the book – I just didn’t have the time when I was making the film to pay attention to all that.

SM: How did you choose the images to include in the book?

AC: It’s always difficult. You fall back on some of the ones you might call your ‘Greatest Hits’, but then you check again to see if that was really the best shot from that photoshoot – and then there are new ones.

SM: Is choosing the most difficult part?

AC: The image edit and the layout. The guys who did the design, M/M from Paris, did all the lettering for Björk and that stuff – they are really great. The lettering, and the years (shown in the book’s chapters), is very playful, and I think that was really great for this book to make these chapters.

SM: Are you working on a film now?

AC: Kind of. I’ve shot it and I edited it, so there are just a few small things that need to be discussed. That will come out in a year’s time. It’s with Helen Mirren and some other great people.

Iggy Pop, New York, 2003

SM: I read that you said that “All photographs must have something about the person, something about you, and be unlike anything seen before.” Is that true?

AC: Ideally. I always try to have these three points. It doesn’t matter how they converge as, when all three are part of the picture, I think you’ll be OK. To have a bit of yourself the whole point is it does matter if there’s something in there.

Otherwise, everybody else can take that picture, so there has to be something of yourself in that shot that makes it yours. Ideally, you make a photo that people don’t know yet.

SM: Do you have any favourite images or photo sessions from your career?

AC: The first 560 pages of the book! Obviously, there are pictures that I find less good than others, but the way I work is that I usually go to where people are, so there’s a journey involved. All these pictures remind me of journeys to go to places and, even if the picture maybe isn’t great, the memory is very positive.

I just really enjoy meeting people and taking their photograph – it’s a very simple life I think. Unfortunately, my life is not so simple, but the idea of it is like a simple idea. You meet somebody; you take their photograph, you go back home and you develop your film.

Ai Weiwei, Beijing, China, 2012

SM: Do you still get a buzz from photographing bands?

AC: Yeah. I prefer individuals to bands, but I’m more known as a band photographer. I took some pictures of David Gilmour recently, and I really enjoyed that, but I never photographed Pink Floyd.

SM: In terms of music photography today, it’s very controlled and curated for artists. I guess that’s not what it used to be?

AC: I don’t know, because I’m not in the situation where I’m depending on that now. I remember in the 1980s I was in Atlanta to photograph The Police for the NME. Their manager, Miles Copeland, came to me with a contract that I could only shoot three songs and I said, “I’ve come all the way from London, you must be joking.”

I tore it up in front of him and I walked out. Then he came after me and said, “OK, you can shoot the whole gig.” I was never keen on these rules. I always tried to fight it.

SM: Shooting Joy Division in London with Ian Curtis looking back at you… You couldn’t have known how iconic that photograph would become?

AC: I knew it would be a strong picture but, of course, when Ian passed away, that picture started to look very different. It started to look like I knew something that I didn’t. You can’t redirect that – people read it a certain way, and you have to let it be.

Joy Division: London, 1979

SM: How would you describe the book?

AC: I saw the first 70 years of my life! I’m very happy. I mean, I did three signing sessions with huge turnouts, so I’m really happy that, at my age, there’s still an audience. I don’t take that for granted. But, I have to say that I’m not into perfection at all, but I do work hard at what I achieve.

SM: Have you got a favourite memory?

AC: I think my humble start in London would be good as a memory. Neil Spencer, who was the editor of the NME at the time, introduced me to the writers and they started to sing, ‘I hate the fucking Dutch’, but, nevertheless, it worked out. That sounds like a negative memory, but I’ve so enjoyed meeting so many people…

Going to Nelson Mandela’s house, meeting Miles Davis a few times, and meeting Joni Mitchell. It’s all beautiful things because you felt like you were part of a creative, interesting world. I always felt that Nelson Mandela was like the father of Africa – he was a beautiful man.

SM: What’s next for you?

AC: I’ve got a few scripts and I’ve got to read through them and see if I like any. I’ve exhibitions in Berlin and Tallinn coming up. Every week, there are demands to have some photographs done. Sometimes it’s fashion, sometimes it’s portraits.

On days like this I’ve had a meeting about a project, I had a filmed interview this morning, which took most of the morning, and I have a call for the film tonight – that’s your day gone. There’s a lot of demands on my time – and it’s not always creative.

Corbijn, Anton is the ultimate showcase of the photographer and filmmaker’s iconic work, spanning from the 1970s to today. Available from Hannibal Books