As far as memoir titles go, Bethany Joy Lenz has a total doozy. Dinner for Vampires: Life on a Cult TV Show (While also in an Actual Cult!).

The cult TV show? One Tree Hill, the immensely popular teen drama where Lenz played the scholarly Haley James Scott from 2003-2012. Over nine seasons, Haley would marry the school jock aged 16, go on tour with an obnoxious musician, get run over by Rick Fox (he played a villain), sire the world’s most adorable child, tend to her husband after he briefly becomes disabled, battle with a psychotic nanny and generally prove herself the purest of souls. (Bar the brief dalliance with the musician.)

The actual cult? A religious group known as the Big House Family. It began as a Bible study group but morphed into something more sinister when a new leader, Michael Galeotti, moved the group to a commune in Idaho. In 2005, a 24-year-old Lenz married Galeotti’s son. She divided her time between the Family (her capitals) base in Idaho and North Carolina where One Tree Hill was filmed.

The Family controlled her career, instructing her to turn down dream roles such as playing Belle from Beauty and the Beast on Broadway. They also controlled her bank account, taking more than $2m from her. Her money from One Tree Hill was used to bankroll various endeavours including a motel, a restaurant and a ministry. Eventually she left the cult, left her ex-husband and successfully sued for custody of her daughter.

Last year, she wrote a memoir about her experiences. We spoke to Lenz about her remarkable story.

SM: It’s a brave thing to write about such a vulnerable period of your life. What made you decide now was the right time?

BJL: I was hesitant because of the people still alive who are involved. There are a lot of people who have just tried to move on with their lives and they don’t want to dredge up the past. I want to be respectful of that while also honouring that I need to be able to share my story. That includes my daughter. I’ve been very, very careful about her interaction with this part of my past.

I really had to weigh the value of what I thought sharing my story could bring to other people who have experienced narcissistic abuse against any difficulty that may bring up for my daughter, my relationship with my daughter and the people I still really love and respect who may not want to dive back into this. And I had a lot of great conversations with people who were former members of the group about how they would feel about it and what parts of their story they would allow me to share.

I didn’t write the book for revenge. I was at a place in my life where I was really happy and content and I didn’t need to do this. So it had to be more of a calling, something that felt like this would be valuable in the world. After weighing those things against each other, it really seemed like this would be worth it.

SM: Was the experience of writing the book cathartic, or do you feel you had already come out the other side?

BJL: I thought that I had come out the other side and that I was able to write from a really objective place for most of the book. It was a bit of a struggle sometimes to go back and spend time in my journals. I did have some panicky emotional moments where I had to put them down and walk away. It was hard revisiting words that were said and living in some of those painful moments again so that I could write them from a first person. But it felt good to reclaim power over those moments rather than just being like, ‘It’s behind me, I don’t want to think about it anymore.’

Surprisingly, reading the audio book was really helpful. To sit down and read through the entire thing felt like a final way to close the door on it. I’ve been able to look at it in a concise manner and compartmentalise it all into one document and now I can put it away. So that felt good.

Spending time in those old memories, I didn’t realise how much shame I was still carrying. There are a lot of things in life, cringey memories, where we try not to go there anymore. You put away the pictures and you put away the journals and you just don’t go there. You don’t listen to the songs and you don’t watch the movies and you just don’t do the things that remind you of whatever that moment was in life. So it was a challenge to go and sit in the places where I felt the most shame and allow that objective version of myself – the older, wiser, more healed version of myself – to sit with young me in those moments and walk out of the shame together.

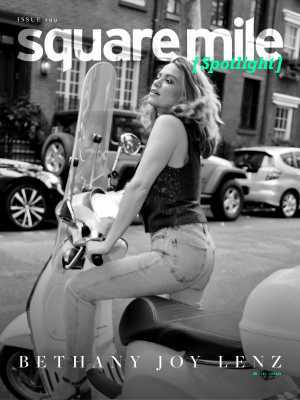

Photography by Tina Turnbow | Styling by Josue Perez | Grooming by Billie Gene

SM: I think everyone can relate to that feeling of not wanting to go near memories that make us uncomfortable.

BJL: That was really a powerful thing and it made me want to do that more so I feel less inclined to shy away from shame. Now I feel like, ‘OK, I’ve done it. I’ve done it in the darkest places so I can do it.’ I realised the alternative was letting all these dark cobwebby corners just live in my house. How long before it takes over? It didn’t feel brave to me. It felt like a necessity in some way. At some point you have to clean your house, so it’s not even brave. I don’t want to survive, I want to thrive. I don’t want to just live in a grey garden’s version of my body and my psyche. I really want a clean house.

SM: One of the things you show through the book is the insidious nature of the group’s leadership – what starts off as a bible study group morphs into something more sinister. Are there red flags that you can spot now looking back?

BJL: I was so young and I didn’t have the wherewithal, I didn’t have the good advice in my life. I didn’t have the right setup of people looking out for me. Looking back, anything that’s exclusive is weird. If there’s a sense of someone wanting to give you something for free except that the only trade-off is that you have to come alone, that you’re not allowed to share it with family members. If someone else is offering you all the answers in exchange for your loyalty. These are themes that ran throughout my history, and it can be hard to spot when you’re young. The isolation is a big part of it.

If you find yourself feeling like someone who really, really adores you, and has been treating you super well, all of a sudden takes you off the pedestal because you didn’t perform something the way they wanted you to, and now they’ve withdrawn their affection, that’s a huge, huge red flag. Coercion, it’s such a tough thing to understand. This is another big thing – if you feel like you don’t have a choice. Somebody may be telling you ‘Oh, you have a choice. You can just choose one of these two options’, but it’s not really a choice because if you don’t choose one of the two options, then you lose your friends or you lose your job or you lose your partner or wherever the abuse is occurring.

The thing that’s so difficult is there are healthy versions of almost all of these things. If somebody has a boundary and they’re like, ‘You know what? If you keep cheating on me, I’m going to leave’, you can’t then turn around and say ‘You’re coercing me into staying.’ The mistake is thinking that there are hard and fast rules you have to follow – and if you follow the rules, whether it’s in an abusive coercive environment or whether it’s a religious environment, nobody will ever take advantage of you. It just can’t be done with a set of rules, and that’s what makes it so difficult to spot, to judge in a court of law, and to help other people see.

SM: How much of your life did you share with people who were outside of that group at the time?

BJL: I didn’t share a lot. I was used to being a bit secretive in life because of growing up in a home where we had addiction in the family. Then being in that modern evangelical environment where you show up on Sunday morning and everybody pretends their life is doing great. You really can’t show up in pain because that means, what, I guess Jesus isn’t working? Your faith isn’t strong enough? So everybody puts on this big smiley happy Sunday face. And so I definitely grew up with a sense of putting on a mask.

You do it as an actor when you show up to work. No matter what’s going on in your personal life, you have to be a professional and show up with your mask on and do your job, regardless of whether you’re in pain or having a hard time in life. There weren’t a lot of safe places for me to let my guard down and be real. On top of that, I was used to being misunderstood because of my ADHD. A lot of actors with neurodivergence are just quirky and direct but people can tend to think that it’s abrasive or bitchy or difficult. And my brain didn’t quite function the way that most people’s do in terms of social interactions. So there’s another mask that I had to learn. I’m playing the role of a normal person who knows how to communicate with normal people, and I can’t just be me and be weird.

Then you drop me into an environment like One Tree Hill where I’m surrounded by lovely, wonderful people. Nobody’s perfect, but we’re all on each other’s team. But the more tight-knit and insular my spiritual group gets, the more inclined I am to believe that anything I say is going to be misunderstood or taken out of context. So it’s better if I just keep it to myself. And predators, or vampires as I would’ve said in the book, really count on that. They rely on their victim’s ability to be loyal, to be insecure about how other people are viewing them, and think they probably won’t be understood or believed or seen. If that’s your default belief about your own life, then you’re a prime target. So I didn’t share a lot for those reasons, and I wish I had, but I didn’t know how.

SM: What do people most commonly misunderstand about your time in a cult?

BJL: That I chose it. That’s the most common belief, I think, toward any adult who’s been a victim of narcissistic abuse. But coercion is real. There are some states with laws against coercion. Especially when you’re young; that’s grooming. That’s been something that I actually misunderstood for a long time too. Thinking, ‘What’s wrong with me that I chose this?’ And the thing was that I didn’t choose it because there was no actual choice. I was completely tricked into something.

If a woman marries a man who’s a con artist and she has no idea, and he’s been conning her the whole time, she didn’t choose of her own free will to marry a con artist, she chose to marry a man who was pretending to be someone else. That’s the big misunderstanding so many people miss when they look at victims of this kind of abuse. And I struggle with the word ‘victim’ because we’re in a culture right now where that’s almost like a badge of honour, and I don’t fundamentally believe in that mindset. I think there’s so much hope on the other side of whatever we go through.

SM: Has your relationship with your faith changed as a result of this experience – and how has that affected your life?

BJL: What a journey. It almost seems like it was God’s kindness to allow me to go through all of that, to get me to a breaking point. I was so committed to what I believed were the right things to do, and how doing the right things would earn me the life that I wanted, and it had to be shattered. That perspective was only leading me into destruction. Allowing me to get to a breaking point where I could just be real and I didn’t have to perform and I didn’t have to do all the right things and be perfect? It released me into a freedom that is scarier because now I actually have to live my own life rather than live by some checklist and just exist. I’m more inclined to take risks and feel alive and feel free.

In terms of the labels of my faith, it’s hard. It’s hard to say that I’m a Christian in this day and age because of what that means right now, especially in America – the Christian nationalism, 400+ years of history in our country of what that word means and the heaviness on women. I could get on a soapbox for an hour about this, but there is a deeply unhealthy version of [Christianity] that is seeded in our emotional and spiritual development as Americans in particular. What I have found through my own personal journey is that version is the counterfeit version. What I’ve experienced on the healthy side is a lot of freedom, love, grace. I don’t feel the need to try and save anybody anymore.

SM: The book isn’t your first venture into writing – you also publish a newspaper, Modern Vintage News. How did that project come about?

MK: I started this broadsheet newspaper because I missed reading the paper. I think it’s romantic to sit and read a paper in the morning with your orange juice and your eggs. And I also miss the brain activation of critical thinking. I noticed that fewer and fewer of BJL friends were spending time reading books or reading a newspaper. We’re just on our phones getting whatever the algorithm is telling us and being fed from whatever sources are popping up on our feed. I noticed this culture of blind acceptance bubbling up. Coming out of a culture of blind acceptance myself, it was concerning to me.

I wanted to create a space that felt very non-threatening. I didn’t want to dive into current events and politics. I’m not qualified to do that, but I am creative and I am qualified as a thinker. We have sections about random things to do in the house. Neurodivergent corner – about different things that we face in life as neurodivergents – and then we have quotes from philosophers or theologians or poets to help people reactivate the critical thinking part of their brain in a safe space. They don’t have to worry about being fed an agenda. The agenda is that we want you to think for yourself.

SM: Looking back at your time on One Tree Hill – why do you think the show resonated so much and continues to do so?

BJL: It’s funny how in the zeitgeist we have these moments that pop up: right place, right time, right combination of elements. This was one of those shows. Between the basketball really bringing in guys, and all of the teenage emotional journeys that brought in girls at first, but I think gave a lot of young guys permission to feel their feelings too. And the fact that it was before social media. The timing was perfect. When it ended, we had reruns, but then there was this little gap where nobody was watching it.

And then people got really inundated with content. Everywhere you go, every streaming outlet, you are bombarded. I think a lot of people wanted to go back to watching something they already knew they liked. Kids who never were alive during the show started to want retro stuff. Now they’re all watching shows about teenagers without cell phones; they’re living a simpler life vicariously through us.

SM: This may be an impossible question to ask about a period of nine years, but did you enjoy making the show?

BJL: Oh, yeah. There were plenty of days when I did not enjoy it, and there were plenty of days that I didn’t enjoy it as much as I now know I should have allowed myself to. But overall, when I look back, we were so lucky and we had such a good group of people; not just our cast, but our crew were really people with hearts of gold. And those relationships meant a lot to me.

Yeah, I did. I really enjoyed it. Of course, youth is wasted on the young, and I wish I could go redo some of that just to really soak it up, but maybe another job another day. There’s always next time.

View on Instagram

SM: You were all very young when the show blew up. Do you think that enough care was given to the cast’s wellbeing?

BJL: Oh, certainly not. No. That was not a priority back then. There wasn’t the conversation about mental health, the conversation about protecting young women. That was absolutely not a part of the dialogue in the early oughts. And yeah, we took the brunt of it back then. Actually, I don’t know if that’s fair to say. I think women have been taking the brunt of it for a very, very long time. But we had a few really wonderful male figures on the show who, in a time when men mostly would just listened to other men, were valuable allies for us and really stood up for us in the most professional way they could.

But overall, in the redo version in my mind, we would have an on-set guidance counsellor. It would’ve been really valuable to have somebody that we could talk to. It’s hard. You’re young, you’re like 20, and people think, well, you’re an adult. It’s the same thing that happened to me with my group. You’re 18 so you’re an adult now – you’re totally capable of making adult decisions and knowing how to protect yourself and knowing how to set boundaries. It’s such an absurd expectation.

SM: There have been a number of harassment allegations about the show’s creator Mark Schwahn. Do you think that’s complicated the show’s legacy at all?

BJL: I think we all deeply hoped that sharing the truth about our experiences would not discolour the love that people have for that show because it was one fly in the ointment. I don’t think you can really throw out the whole batch. And I hope that people don’t, because it wasn’t meant to be a tell-all of what a horrible experience it was. That’s not true.

There were some incredibly dark and difficult moments, but I hope that, much like you can see through the nuance in your own life of dark and difficult moments, that people extend that same grace to their memories of our show. And when they watch it, they can still see all the bright and beauty.

SM: There are rumours of a sequel series. Would you be keen to revisit Haley?

BJL: I’m totally open to the creative future and I think the deal would just have to be right. And the timing. There are so many variables, so many factors. But yeah, I am open to the creative future.

Dinner for Vampires is available now in hardback from Waterstones for £25.