Stephen Lang began his screen career starring alongside Dustin Hoffman and John Malkovich in the 1985 TV adaptation of Death of a Salesman. A quarter of a century later he played the villainous Colonel Miles Quaritch in the futuristic epic Avatar, the highest-grossing film of all time. When both Arthur Miller and James Cameron count you as a close friend and frequent collaborator, you’ve probably done something right.

Lang has spent the past 40 years living out the American myth. He’s done cowboys (Tombstone), gangsters (Public Enemies), baseball (Babe Ruth), every major war from the Civil (Gettysburg) to Iraq (The Men Who Stare at Goats). However, Avatar’s Quaritch will surely be his definitive role, especially as Lang returned for the 2022 sequel The Way of Water and will remain present for the final three films of the series, starting with December’s Fire and Ash.

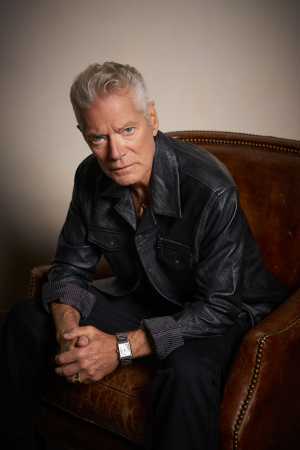

For someone so adept at playing military hard-asses, the man who introduces himself as ‘Slang’ appears the most gentle of souls. Avuncular, softly spoken and possessing a permanent twinkle in his eye, he looks at least a decade younger than his 73 years. The Langs are a formidable bloodline: his father Eugene was a self-made millionaire, while his daughter Lucy currently serves as Inspector General of New York State.

Our conversation spanned everything from the formidable Cameron “the only unalloyed genius that I’ve worked with”, doing Shakespeare with Meryl Streep, and what Lang’s old friend Arthur Miller would have made of Avatar. I hope you enjoy the interview as much as I did.

Square mile: You’ve played Quaritch for three films over 15 years. How has your relationship with the character evolved?

Stephen Lang: Gosh, I remember reading Quaritch and being awestruck with the dynamism of the character, the aggressive forward movement. The fact that he was so articulate, there was so much about him that was so playable.

People would say, “He really is the villain of the piece” – and my answer to that was, “Friends, if I don’t love him, no one will. And if I do love him, he’s going to earn, if not your affection, at least your recognition. You’re going to take him seriously as a character, not just some cardboard villain.” Over the years, the character has become part of the fabric of my life.

Quaritch has changed me, and possibly I’ve changed Quaritch a bit, who knows? That’s more a question for Jim Cameron. I do know that my affection for the character, my respect for the character, and my absolute horror with what the character is capable of doing, has only increased over the years as the stakes of these films have revved up. In one sense, my approach to the character is no different than it was on day one. In other ways, I think it’s been highly complicated and become much richer and much denser.

Over the years, I’ve become more benign. I’ve come to certain conclusions about life

SM: Quaritch is a more complicated character post-resurrection. What can you tell us about his journey in the third film?

SL: Things get more complicated. Without giving anything away, I can guarantee there’s more of that. Things only get more and more confusing. Is confusing the word I want? I’m not sure it is. Things get more complicated for Quaritch, the answers are not quite that simple.

He’s always looking for the straightest line. He’s always looking for the most effective solution to the problem to solve his particular agenda. Things have not changed in that he is a wolf with a bone, and the name of that bone is Jake Sully. That does not change. However, his relationship to Jake Sully and to others will undergo all kinds of transformations.

SM: I love the scene in the second film when you crush your own skull, a phrase one rarely gets to use. That was your idea?

SL: Yes it was. I always thought it would be necessary to discover the remains of your own self. Taking that skull and contemplating it – what do I remember about this guy? Am I this guy? This is the guy I was. And by crushing it the way he does, that’s so pure Quaritch. He doesn’t set it aside to contemplate it later. He crushes the skull. That I believe operates as a repudiation of the past and a pathway forward for him. I negate my failure, I negate my humiliations, I move forward.

SM: You wrote Beyond Glory, a one-man play about all the soldiers who won the Medal of Honor. Did your work there inform your portrayal of Quaritch?

SL: First of all, the work I did on Beyond Glory informed my work on this a lot. The two are linked, by the way. Have you ever looked at the AMP suit in the original Avatar? There’s a tattoo on the side that says ‘Beyond Glory’. It’s on every action figure you’re going to see.

Jim Cameron said to me, “We should put a tattoo on the side of your AMP suit.” We were thinking, should it be a dragon? Should it be a serpent? Should it be an eagle? And he said, “What about your logo for your show Beyond Glory? That works.” It was very moving that he would do that.

I don’t think that I would compare Quaritch to any of the characters that I portray in Beyond Glory. Partly because he’s a fictional character, and these were real, living, breathing men – all of them are gone now – who did extraordinary things. These were ordinary men who did extraordinary things under extraordinary circumstances.

Quaritch is not an ordinary man at all. He’s a bit extraordinary; I don’t care how many people you put in the room, he’s going to be the alpha.

I was fortunate enough to work with and to drink with and to speak with a true titan of American literature

SM: You said Quaritch has informed you in some ways. Are you more alpha now?

SL: I dunno. Over the years, I think I’ve become more benign. I’ve come to certain conclusions about life, my life, what it is to lead a good life over the years. I’m a grandfather to six, I’m a father to four. I’ve been married to Tina for 45 years. That teaches you a lot of things. It teaches you patience, it teaches you humility. And more than anything else – and this is not just a family thing, this is something one extends to everyone – it teaches you kindness.

Does that inform Quaritch at all? Well, you know what? In some way it must. I don’t think I’m prepared to sit here and to quantify that. I don’t think I’d be able to do that for you. But you bring yourself to whatever it is you play.

I think over the years that I’ve become a more rounded person. But talking about alpha males? It’s interesting – when I come on set, I go pretty much full Quaritch and I’m on set with Jim Cameron. What does that mean? I’ll tell you what it means. It means there are two alphas in the room. That creates a wonderful situation. We’re both aware of it, and we’re both aware that the crew is aware of it and the crew likes it.

SM: One of your first TV roles was Death of a Salesman. What an incredible journey to go from the most famous American play of the 20th century to the biggest blockbuster in cinematic history.

SL: You’ve put your finger on something interesting there because I could make a case that Death of a Salesman and Avatar are the two most significant jobs that I’ve ever been given. One, Death of a Salesman just kicked off a whole Broadway thing for me and really put my career in gear. And Avatar was the culmination of years of work. In between there have been many, many other projects that are very near and dear to my heart as well. No doubt about that.

SM: I know you were good friends with Arthur Miller. Are there similarities between him and James Cameron?

SL: Whoa, whoa, whoa. [Laughs.] I could rack my brain here… They’re both tall. I would say that they both are extraordinary. They both were extraordinary writers. Arthur was, Jim is.

I discussed Death of a Salesman with Arthur on more than one occasion. I was with him quite a lot. And I always felt that Death of a Salesman was kind of written through Arthur. He was really just vibing. The writing in it, you really have to read it and work on it to appreciate just how brilliant it really is. It’s an extraordinary piece of theatre. Absolutely. In its time, it was revolutionary as well because of the messing around with time that he does.

The original title of that play was Inside His Head, and in a way that entire play does take place within the tortured skull of Willy Loman. Of course he wrote so many other wonderful plays as well but to my estimation, the Salesman stands above everything. So I was fortunate enough to work with and to drink with and to speak with a true titan of American literature, American theatre. And I feel pretty much the same with Jim.

Jim’s talents are wider because Jim is a superb writer and storyteller, but that doesn’t cover it. He’s like an engineer. He’s a brilliant engineer. He’s totally in touch with all the physical parts of working, of acting, the fighting, all of that. Jim knows a lot about a lot of things.

So, gosh, my response is that I’m just so fortunate and privileged to have known both of these fellas and to let some of their genius rub off on me. And I don’t use the word genius lightly at all. Jim Cameron is the only unalloyed genius that I’ve worked with. I’ve worked with some very, very great, smart people. But I will also say that Arthur Miller, whether he’s a genius or not, doesn’t matter – Death of a Salesman is a work of pure genius. It’d be interesting for those two to have dinner together.

I’ve always thought Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy is one of the darkest and coolest stories. I’d love to take that particular journey into darkness

SM: What do you think Arthur Miller would’ve made of Avatar?

SL: Oh, he would’ve said, “Oh gee. Wow!” First of all, he’d have said, “You were pretty big. Look at those muscles on you there. Wow. That’s quite a thing you guys did.” He’d kind of hem and haw about the whole thing a little bit. I’d say, “Arthur, did you like it?” “Sure I did. I thought it was great.” I think he would’ve loved it.

SM: Over your career, you’ve done the American Civil War, the Wild West, Prohibition, gangsters – you’re living out the American story on screen. Is there any particular period that you’d like to explore?

SL: There are many. The labour movement is something that’s always been interesting to me. I’ve never really done much in the political arena. I’d say that would be of interest to me as well. My goodness! I always wanted to do the Transcontinental Railroad. I think that’s an amazing story as well. Gosh, I’d love to do a shipboard story at some point. I love films and stories about the sea. I’m a huge fan of the Master and Commander series, it’s one of my favourite things in the absolute world.

Occasionally, you’ll hear of a project where you go, ‘Oh boy, I so much want to be part of that!’ Sometimes you’re fortunate enough to actually be part of it. The one right now that hurts my heart just a little bit is the fact that Christopher Nolan has done The Odyssey. I know The Odyssey pretty well, I’ve read it with my grandson and granddaughter a number of times. That’s a project that, well, number one, I wish I was in that thing, but number two, I’m not in it, so I can’t wait to see it.

I love myths. I love where myths and history begin to coalesce. I did this project called House of David, I play the prophet Samuel in this series for Amazon. When you play Samuel, you are playing a historical figure, a character from 3,000 years ago. But he comes at a time where history and legend and myth all begin to coalesce. And I love that because you make decisions about how you want to represent the truth.

There is one, I know people have been trying to make it for years, but I’ve always thought Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy is one of the darkest and coolest stories. I’d love to take that particular journey into darkness.

SM: Who would you want to play?

SL: [Smiling] Who do you think I want to play? [Judge Holden, one of the great villains of American literature.]

SM: You’d have to shave your head.

SL: Happy to shave my head!

SM: Your dad Eugene sounds like a remarkable man. A self-made millionaire who donated millions to charity and encouraged you to forge your own path. Is that all correct?

SL: Yeah, it’s correct. He’s gone now about eight or nine years. He was a great guy. He and I were very close. He was a tough guy. He was probably the toughest guy I’ve ever met in terms of negotiation. If he believed in something, he wasn’t going to give an inch on it. He had very high standards. He had the soul of a social worker but he became a multimillionaire.

He was so damn smart and good at business and everything, but it would be foolish to say that money wasn’t important to him. It was important because of what you could achieve in creative ways. If my father has a legacy, it really is that he taught a lot of people that philanthropy, charity is not merely giving money away to people who need food or shelter or clothes. It’s creating opportunity for people and it’s creating challenges for people as well. He was adamant about that.

Very interesting guy. I think about him all the time and miss him. He left his mark on me for sure. He was a real New Yorker. He was New York through and through.

Working with Dustin Hoffman was kind of a years-long lesson. Dustin was relentless

SM: Speaking of New York, your daughter Lucy Lang is the current Inspector General. You’ve done something right!

SL: I don’t know how these things happen. My daughter Lucy blows my mind. She’s the Inspector General of New York State. She wields a lot of authority, but she wields it with such grace and such compassion and such intelligence.

I’m 73, but in a way I regard my own position in the family kind of as emeritus at this point. I really think of Lucy as the leader of the family in a lot of ways. At any rate, I usually do what she tells me to do.

SM: That’s always a wise move, for sure.

SL: Well, I’ve been married for 45 years, so I’ve learned something over the years.

SM: You’ve worked with some unbelievable names throughout your career. Did you ever get any advice or a lesson that stuck with you?

SL: Working with Dustin Hoffman was kind of a years-long lesson. Dustin was relentless. He was a relentless artist. He was constantly probing, constantly searching, constantly poking. And we did that on a night-to-night basis. When we did Death of a Salesman, when the curtain fell at intermission, John Malkovich, Dustin and I gathered together and did notes. We did that for almost 200 performances. That in itself was an amazing lesson.

Some others? Early in my career, and it was early in her career as well. I was in Henry V with Meryl Streep. And to be part of that, to watch Meryl, the ease with which she worked was really quite extraordinary. We were doing Shakespeare in the park, and we were sitting on the grass after rehearsal or something like that, just actors sitting around talking, five or six of us.

The actor playing Henry was an actor called Paul Rudd, not the Paul Rudd of today. He was another actor and he was a good actor, excellent actor. You look him up. He’s gone now, rest his soul. He had a lot of success in the 1970s. He was playing Henry, and Meryl was playing Catherine. Some asked her, “How is Paul? How do you like working with Paul?”

She sort of cocked her head and smiled. She said, “Oh, Paul, he’s so easy to love.” And that was such an amazing thing to hear because to me it was a real double-edged comment in a way. Because it’s like, “Do I want to be easy to love?” I don’t know if I can explain myself but I made a decision at that moment, which was: I will never be easy to love. You know what I mean?

View on Instagram

She wasn’t damning him with faint praise. Perhaps she was, I don’t know. But what she was saying was, there were no obstacles. It wasn’t difficult. To me, it’s always been about the obstacles. If there are no obstacles, I’ve got to create some.

And some of the other greats, working with people like, oh my gosh, Gene Hackman, one of the greatest of all time. The simplicity with which he worked, the contemplative, the thoughtful nature of the work that he did was extraordinary. Working opposite Robert Duvall was one of the great privileges of my life.

There’s a common kind of dynamism and brilliance to both Duvall and to Hackman. Very different actors, of course, but generationally they’re from the same place. And I’m so fortunate, I hope something rubbed off. But if there was one, and he’s a very different type of actor than myself, it would be Dustin. Dustin had a profound effect on me.

SM: You’re in incredible shape. How do readers ensure that they look even half as good as you in their seventies?

SL: Just got to do it every day. Just practise. Listen, what I do is based upon my work. I’m not a painter. I don’t have a violin. I’m not a sculptor. The only tool I have is me from head to toe. So I don’t want to limit it. I want it to be as good as it can be. As you get older, things begin to deteriorate. And if it’s happening for me, it’s happening for other actors as well. We’re all getting older.

So I think, is there some way that I can cut the odds a little bit? Is there some way that I can keep going and maybe be in the proper shape to do this gnarly role if they need some tough old bastard. That’s what keeps me motivated. Also, there’s a certain degree of vanity involved as well. And I will say that vanity, I understand that it’s a sin, but I don’t believe it’s one of the seven deadly sins. I think a certain amount of vanity is pretty crucial.

Some of it is vanity as well, to keep yourself in the kind of shape you feel good about. I want to feel good about myself. After I finish my day’s workout, a lot of times I’m done by 11am, I feel like the rest of the day is mine. It’s all gravy.

Avatar: Fire and Ash is out on 19 December.