This is not a magazine. This is not a conspiracy to force opinion into the subconscious of stylish young people. A synthetic leisure culture is developing – plastic people force fed on canned entertainment and designer food. Are you ready to be Dazed & Confused? Get high on oxygen! This is urban ideas for creative people. People who want to read – something else.

Thus ran the manifesto that opened the first issue of Dazed & Confused in 1991. It was a single A2 newsprint, its creators Jefferson Hack and John Rankin Waddell still students at the London College of Printing. Hack did the words, Rankin the pictures, with their fellow student Katie Grand later coming aboard to sort the fashion. Over the next few years, the magazine would establish itself as one of the most dynamic and innovative in the world, the glossy bible of Cool Britannia, a publication that didn’t just cover the zeitgeist but created it.

Unsurprisingly there are ample coffee books and art exhibitions celebrating the Dazed glory years. I meet Rankin as he prepares to launch one of the latter, Back in the Dazed: Rankin 1991-2001, which runs until 23 June at 180 Studios in London. The walls of the gallery are adorned with various landmark images that encompass everything from offbeat celebrities to crying models to a woman being set on fire.

“We wanted to create culture,” Rankin tells me. “We wanted to make something. So I’ve always said that the magazine was a bit of a Trojan horse or a conduit for our bigger vision, which was to create art. To create political statements. Look at who we put in it – every cover’s different.”

As we’re sitting at a table covered with past issues of Dazed, I can attest that, yes, every cover was different. This creativity would be replicated across multiple industries from fashion to music to art. “We all broke into the 1990s like we were owed something,” says Rankin. “It was like, smash and grab. We just broke in.”

We spent an hour discussing his memories of a decade that still exerts a vast cultural pull. Glorious days, glorious Dazed.

Square Mile: Who came up with the initial Dazed manifesto?

Rankin: It was Jefferson, but the ethos was both of ours. So there’s no question there’s a lot of me in there. The two of us together, we were like separated at the hip. We were dazed and confused!

SM: Which one was which?

R: Well I always really liked dazed as a word. Also, our names are Rankin and Jefferson so his is longer than mine. I always thought of the ‘and’ as infinite. We were yin and yang to each other. It lasted a long time. It lasted a good ten years, which is quite a long time. And we were young.

SM: What made you create a magazine?

R: We were all at college [LCP] together. The minute I walked into college for the first time, a girl handed me a student magazine – she was the editor. From that first day, my college course was photography and in parallel I did student magazines. That was my social life.

From that we did events, nightclubs, parties. I was a student rep for two years, one year as communications manager, one as campaigns manager. Almost in opposition to what you are learning at college, you learn how to make money – because you have to make money to do the student magazine.

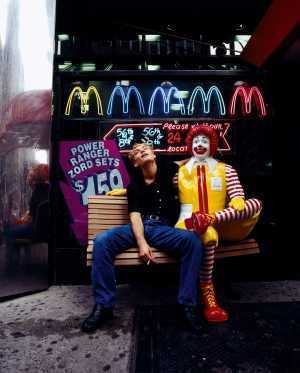

Jude Law, A Law Unto Himself, Dazed & Confused, Issue 15, 1995

“This shot of Jude was taken while we were both in New York. I actually spent quite a bit of time with him then, as I knew some people who knew him and we just started hanging out together. Eventually I suggested a shoot together which was just him and me running around the streets of Manhattan. He even climbed lampposts. This image was when we passed by a McDonald’s with a plastic statue of Ronald McDonald outside. It felt funny to have Jude, who was just starting to get famous and was breaking America, interact with such a symbol of their culture. This picture we got from that moment remains one of my favourites, capturing the spontaneity of our time together.”

Rankin

SM: And you formed Dazed as soon as you left college?

R: We actually did it at college. We used the student union equipment – we couldn’t afford an Apple Mac so we borrowed one from the student union. We had an amazing caretaker who used to give us a nod when it was free. We always took it back!

We didn’t borrow it during the week that much because it was too much of a hassle to get it out at seven o’clock in the evening and then get it back in at seven in the morning. But during the weekends we used to do all our work on the beginnings of what became Dazed.

SM: Presumably you’re not setting out to create a decade-defining magazine?

R: Oh god no! Back then, we were very ambitious but we never thought it would be something that was around this long. I remember laying down the three covers and being like, ‘Wow, I’ve created this!’ It was me and Jefferson for the first two years and then we met Katie Grand. We were super naive. We were very, very young. I was 24. Jefferson and Katie were even younger – 18, 19.

We did a supplement shoot in New York for Sony MiniDisc. We didn’t have a credit card and the only person we knew that had a credit card was Katie’s dad. So we used it to book the hotel and then we got to New York and we spent all the money that we had. We didn’t have any money for the taxi back to the airport.

SM: What do you spend the money on?

R: Going out! Going out, going to parties. That was what the magazine was about – going out, connecting with people. So we were all sitting there at the hotel going, how the fuck are we going to get back to the airport? So we booked a limo on the room and we charged it to Katie’s dad’s credit card.

We all get in the back of this limo, playing hip hop, feeling like kings of the world. That was how we rolled. Katie’s dad was really pissed off and then we spent three months paying him back. I think she’ll probably tell you it was a year.

U2, Twisting My Lemon Man, Dazed & Confused, Issue 30, 1997

“U2 are a gift for photographers. They’re easy to photograph because they don’t hate the process, and they’re creative in their image making as much as they are in their music making – they see it as a whole package. Every so often there are people you meet who just have an undeniable energy; Bono is one of those people. He is still so gracious to be part of the process, even though he’s been doing this for decades now.”

Rankin

SM: Do you think your youth was an advantage or disadvantage?

R: I think it was an advantage because we were so ambitious and we were called upstarts. We were called out by the media – ‘Who the fuck do these kids think they are?’ But I read recently that in 1995 or 1996, Anna Wintour namechecked us in an interview.

Someone asked her the difference between America and the UK. She said, ‘I’ve heard about these two young guys who have set up this magazine in the UK, literally hand to mouth, and it’s doing really well. In America, they spend $5 million and nobody knows about it.’ The first few years, we didn’t really care about the money. It was about just getting it out, get it out, get it out.

SM: When did you feel like you had arrived as a publication?

R: Ninety six. We got Kylie Minogue, we shot Björk. They’re the ones that catapulted us. We did Björk, the Kylie Bible and then we did Pulp. Suddenly we were taken seriously. From 1991 to 1995, everyone just thought we were snotty kids.

SM: Would you say you helped to create the idea of Cool Britannia – or that you rode its wave? Right place, right time?

R: It was partly right place, right time. It was desktop publishing, it was a love for the new. If you were my age in 1990, you’ve got Jarvis Cocker, you’ve got Oasis, Damien Hirst, you’ve got Alexander McQueen, you’ve got Stella McCartney. All these kids who have grown up in a period where we’d all watch BBC Two, we’d all like the same music, we all loved punk, we all read the same books.

We all got an amazing education – between 1970 and 1990, everyone got a really good education. Even if you went to a normal school, you got a good education. So I think we all had that shared experience. You could go to college and do art. There were so many ways of getting supported financially by the government.

We were all very influenced by the 1960s and we were all very influenced by Malcolm McLaren and the Sex Pistols. Going to the movies, watching TV, watching The Young Ones – all that alternative comedy.

No one has that now, we were the last generation that had it. Maybe the naughties had a little bit of it as well.

Helena Christensen, Flesh For Fantasy, Dazed & Confused, Issue 33, 1997

“Helena was the first supermodel we featured in Dazed. We knew it would be a game changer for us if she was on the cover and it was. Plus, I was little obsessed with her, as she was just so extraordinary in photographs. On the day, she turned up, could not have been more fun, and really got into the spirit of what we were shooting. She told me she was a photographer and asked to take some pictures of me. They are some of the best photographs of me ever taken.”

Rankin

SM: There’s a famous line from the film Easy Rider about the lost promise of the 1960s – “We blew it.” Do you feel the same about the 1990s?

R: Yeah, I think we all started hungry. Most of us had nothing at the beginning. Working class people, working class kids were given confidence to do stuff and be quite brave at the same time. We all broke into the 1990s like we were owed something. It was like smash and grab. We just broke in. We smashed through the decade like, you fucking owe us it.

Jefferson and I had a conversation – ‘Shall we try and get jobs?’ And we were both like, ‘Nah, let’s just try and do it ourselves.’ That ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude came from that shared experience because what was there to lose? We just gave it a go.

We were all very well read. If you ever interview any of the people from that period, they’re super-clever people. None of them are stupid; I never met any thick people. You’d go to nightclubs, get fucked up, and have really clever conversations. You were talking about philosophy, how we should challenge the conformity of today.

So we took it and shook it and went ‘It’s ours: get the fuck out of our way.’ It was like being mugged by a load of quite clever kids. We wanted it. And there was no indecision. We all wanted to be famous and we all wanted to be successful and we weren’t scared of asking for money. Although it wasn’t about the money – we weren’t going, ‘Oh we’ve got to make £20,000 on this issue.’ No, we’ve got to make £20k to make the issue. The money was literally about making it happen.

SM: Can you talk us through a real pinch-me moment?

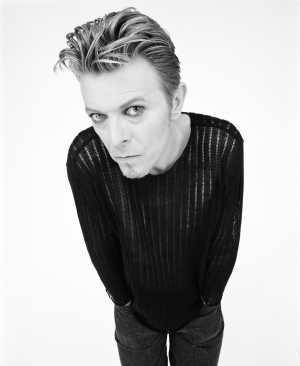

R: In 1995, I’m something like 28, and I’m flying to LA to photograph David Bowie. That was definitely a pinch-me moment. He was like Tigger from Winnie the Pooh. It was like Tigger had come into the room – he was so enthusiastic, so excited, so amazing, so fucking cool but not cold. I thought he’d be cold and distant.

Thom Yorke was another one. Jefferson and I had always wanted to do this concept where we got people to interview themselves and it was always really hard. People didn’t want to do it. And Thom Yorke was like, ‘No, I think it’s great.’ So he wrote out a load of questions, got drunk and answered them. It was so rock’n’roll.

David Bowie, No Different From Anyone Else, Dazed & Confused, Issue 15, 1995

“Bowie was one of the first celebrities I photographed. It was back in 1995 and I really thought I hit the big time with this shoot. It was a surreal, whirlwind trip to LA, flying in on Wednesday evening, shooting the next day and back on the plane on the Friday afternoon. This particular shot was among the more conventional ones we captured together, really exemplifying the style of most of my work in the 1990s: Bowie leaning into the camera, shot with a wide-angle, his gaze meeting the lens directly. He really was just extraordinary to photograph. My initial thought was that he was going to be too cool, almost a bit ‘off’ with me, but he was the exact opposite. He reminded me of Tigger from Winnie-the-Pooh, bouncing around being really playful and funny.”

Rankin

SM: With photoshoots, were you led by the person or the concept?

R: Always by the concept. So my idea for Bowie, which didn’t really work, was morphing his face together with an old woman and a baby. I was going to create different Bowies. I think I was going to call it Morph. But I couldn’t afford the retouching.

SM: What was the biggest budget you ever spent on a shoot?

R: About 50p! We didn’t have any money. The Michael Jackson impersonator was probably the most expensive shot. I shot the impersonator and then I retouched him to look like Michael Jackson.

SM: Did you interview Michael Jackson?

R: No! It was fake.

SM: Was that legal?

R: I don’t know, but back then who knew?

SM: Do you think three students could launch a magazine like Dazed now?

R: No. I don’t think it could become as successful. I think you could probably do it. The whole way that the media works now is that there aren’t any magazines. To launch a kind of indie is not impossible. People are still doing it. But you can’t get that kind of success again because when we were doing it, we were part of a larger group of people that were all doing the same thing in music, art, fashion.

We wanted to create culture. We wanted to make something. So I’ve always said that the magazine was a bit of a Trojan horse or a conduit for our bigger vision, which was to create art. To create political statements. Look at who we put in it: every cover’s different. We did a cover that was just a mirrorball and we ran with the coverline, ‘Death of the cover star’.

There was an intent: XL models in a shoot, grandmothers in a shoot, people of colour, LGBTQ+. We didn’t go, ‘Oh, we’re going to challenge everybody by putting a gay black guy on the cover.’ We were like, ‘He’s amazing. Why isn’t he a cover?’ It was being led by the idea, it was being led by our instinct. We did so many issues where we would hand the magazine over to a guest editor like Paul Smith, Alexander McQueen. We were making culture. We weren’t working for someone else, we were working for ourselves. We all saw the magazine as an album. Every issue was an album. We were a band with guest singers.

When the decade began it was all very exciting and then it ended with me doing a parody of Michael Jackson. By 2001, we’d all had enough of each other.

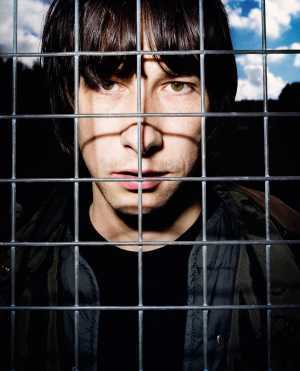

Bobby Gillespie, Hide & Seek, Dazed & Confused, Issue 37, 1997

“Bobby is one of those people that I knew for ages on the scene in London. This photo was taken across the road from the Dave & Confused offices in Old Street, in a kids’ playground. I just loved the idea of him being behind the grill, as growing up in Glasgow, with football, these kind of playgrounds were everywhere, so it felt familiar and appropriate.”

Rankin

SM: Would young creatives now, the Rankins of today, even do a magazine?

R: I think they’d be more self-focused. How many bands are there now? How many new bands are coming through? People think of the easy route. We had a lot of critical thinking – the whole manifesto, it sounds quite innocent, but it was still thought through and thought out. And we wanted to be an open-access magazine. We wanted to change publishing. There was critical thinking. I don’t think that happens anymore. People look to their own journey.

One thing I regret is not enjoying and giving love to the people I worked with. Because we were always fighting. About everything. The pages, the design, how many shots you would use, what it looked like. Because we were young! It’s why bands don’t stay together. Normally when people come into a magazine, they’re probably hitting their thirties, they’ve had a life, they’re more mature. We were fucking kids! We grew up with one another.

SM: When did you leave?

R: I left properly in 2009 but the last eight years, I wasn’t really fussed. I was part of a band and by the end of the 1990s, I wanted to go solo. I remember a meeting when I was getting platitudes from a new editor and I thought, ‘You know what? I think you’re full of shit.’

I was saying it’s really important that this magazine has politics in it. It’s really important that we have a reason for being. It’s really important that we put that front and centre of what we’re about. We’re about ideas. I want an idea, you’ve got to give me an idea. What’s the reason that I’m putting this person in the magazine?

And by the end of the 1990s, we weren’t doing that. We’d become a magazine. We’d gone from being an album every time to being a fully functioning magazine – which is what we’d said we weren’t. There was nothing wrong with that. It was the right thing for the magazine itself. But I remember thinking, we are losing a part of it that I really believed in. When I left, they got that back again in spades. So maybe it was me that was blocking it.

At the beginning of the decade, Jeff and I made a promise to each other that if this went well, we wouldn’t be those old men hanging on to youth. Because we’d watched it in other magazines. You can’t be 40 years old pretending to be the voice of youth culture. And both of us stuck to that. He gave up the editor’s role at the end of the 1990s and I left as creative director about 2002, 2003. We were done.

If you look at the magazine through that critical eye, you can see that there’s politics – body politics, personal politics – going through it. But it was filtered through this seductive, glossy thing. We definitely felt like we were doing something really innovative. But then ten, 20 years later, people are going, ‘Look what I’ve just done. I’ve reinvented fashion!’ No, we did it 20 years ago.

‘Back In the Dazed: Rankin 1991-2001' celebrates stand-out imagery from over 200 editorial shoots by Rankin for his magazine Dazed & Confused. The exhibition is on display until 7 July at 180 Studios, London. Tickets available from 180studios.com/rankin. 'The Dazed Decades 1990-2016' by Rankin is available for £40 from rankinswag.com alongside a number of limited-edition prints.