Denis O’Regan knew that it hadn’t gone well with Paul McCartney. The rock photographer – best-known for his dramatic live performance and intimate backstage shots alike, touring with everyone from Kiss to Queen, The Rolling Stones to David Bowie, and being the official photographer of Live Aid to boot – was just too nervous.

“The cliché of shy people hiding behind the camera is absolutely true in my case. There was a time when if I could, I’d have had a hood over my head – you know, the kind that old-time photographers used to use,” he laughs. “I’m not usually starstruck – except with Paul McCartney. I was just such a huge Beatles fan, so I wasn’t myself the day I auditioned to be his tour photographer. I wasn’t funny or relaxed. It was just overwhelming.”

Decades on, O’Regan can bury any regret as he rides the wave of recent years’ critical reappraisal of rock photography. He has a 69-day exhibition at London’s West Contemporary gallery (to mark his 69th birthday), a release of new prints to raise money for children’s charities and, out next year, a monolith of his work being published. But, more pertinently he argues, he’s riding the wave of a critical reappraisal of the performers he’s worked with, too.

“They were pop stars back then, but now they’re cultural icons,” says O’Reagan. “You can see how these acts have made a transition from superficial pop star – as many people saw them – to something much more profound, especially when they die.

“And I think there’s a sense now that there will never be another Beatles or David Bowie or Freddie Mercury. They got there first and defined the form, but they also went beyond the norm. These days Instagram has killed the mystique – there’s too much information. The world has shrunk. I think maybe we’re at the end of an era.”

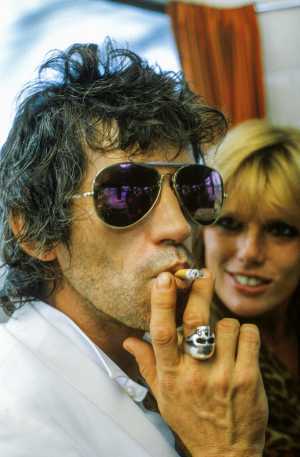

Keith Richards

Denis O'Regan

Bob Marley

Denis O'Regan

It’s one O’Regan has been at the forefront of documenting. Of course, there’s a technical skill to what O’Regan does – “you have to be a sniper trying to catch moments,” he explains – especially given that so many of his best-known images come from a time before digital photography, when an itchy trigger finger would literally cost him money. Back then, every shot cost him a pound, there were only 36 shots on a reel and, since he was mobile, he could only shoot as much as he could carry.

“And trying to catch the moment when, say, there are hundreds of stage lights shining at you isn’t easy,” he chuckles. “It means you have to train yourself to shoot manually, without relying on what the camera tells you, because it will just be fooled [by the environment].

“Of course, it helps when these people are all so photogenic. But I look back and sometimes think if I hadn’t been there all these historic moments – the rise of Ziggy Stardust, for example, or the only time David Bowie and Michael Jackson met – would have been lost.”

Indeed, on reflection it occurs to O’Regan that maybe the talent that has really seen him through is less camera management as people management; less the ability to see a defining image, as the ability to read egos, to back off when required and at other times to push hard.

Take the time he was let go by The Rolling Stones mid-tour on the simple basis that the band liked to change things up occasionally. O’Regan pointed out that Keith Richards liked his photos but that Mick Jagger hadn’t even seen them – so Jagger’s PA went off to talk to him, returning with the news that O’Regan could stay. O’Regan was still with the band at the end of the eight-week tour.

David Bowie with Mick Jagger

Denis O'Regan

“It was only in retrospect that I looked at any of these meetings you have as auditions, but that’s what they were. I spent a whole flight sat next to Mick, with him talking solidly all the time about his house on Mustique, his ex-wife – whom he never referred to by name – and obviously that was my interview,” recalls O’Regan.

“I pitched up at David Bowie’s tour rehearsals and for the first few days I’d have to go to the gym every morning with him and his bodyguard, and of course that was him deciding whether he could put up with me for months on end. The thing about these tours is that [as a photographer] you have to be trusted and, maybe more importantly, you have to fit in and get on with people. You can’t constantly be going ‘Mick, Mick, over here, Mick!’ because it drives them insane. I’m inherently lazy so I’m never pushy like that anyway.”

You wouldn’t imagine that from his roster of subjects: The Who, Blondie, Dire Straits, the list goes on. Nor, indeed, from the commitment required to being away on the road for, in some cases, years at a time – something O’Regan hints at as having a less than positive impact on his home life. But then the tour is O’Regan’s natural habitat.

“Sadly,” O’Regan laughs, “in order, my passions have always been music (though, I couldn’t stand Iron Maiden every night), travel, and only then photography. Bowie once told me that rock’n’roll is in my blood and I told him no, because I didn’t want to seem that shallow. But he was right.”

“I think that’s in part because the excitement of being around the energy of a live performance is still there for me after seeing who knows how many gigs,” he adds. “The audience is always there to have fun. They’re always happy. It’s not like a football match in which half the crowd are inevitably unhappy. OK, so I think initially [my enthusiasm] for touring was because I was always on the hunt, so it’s useful to be with, say, Duran Duran and 20,000 screaming girls. But as I got older it became more about getting those special shots.”

Getting to take those shots in the first place required a leap of faith. O’Regan began his working life at an insurance brokerage. But he enjoyed taking photos on the side – “capturing dewdrops on a leaf, cobwebs in the autumn,” he gently mocks – and, enthused by the increasingly theatrical performances of the time, especially at gigs. But without connections, portfolio, press pass or commissions, access was limited. Until punk.

“That opened all the doors which until then were shut to me. Suddenly the photos that the music papers wanted the most were the ones that were easiest to get. You’d pay your 75p at the Marquee and in you went.” But O’Regan realised that being in a pit with a dozen other photographers was no way to get something sellable. For that he’d have to be an official tour photographer.

Luck came calling. O’Regan asked an NME photographer to borrow his flash. “‘I don’t like all this punk stuff, you send your pictures into the paper,’ he told me.” But the NME snapper also happened to share a house with Phil Lynott of Thin Lizzy, who were about to tour – “and that, I knew, was the lifestyle that I really wanted. I just said to Phil, ‘Can I come?’ And he said, ‘Alright’.”

Mick Jagger at Slane Castle

Denis O'Regan

Freddie Mercury flexing

Denis O'Regan

O’Regan loved touring, though it wasn’t for everybody: Freddie Mercury, he recalls, absolutely hated it. He concedes that it became repetitive: the same hotels, the routines: “Everyone was absolutely hyper after a show, so going to sleep was just impossible and since restaurants were closed all you could do was party.” On the other hand, “the five star hotels with your own floor, the police escorts, women everywhere, it was great.”

He got to be up close to obsessive fandom and its screaming adulation but with the luxury “of being able to walk away, while they [the artists] can’t. To see Duran Duran-mania up close – the girls appearing out of nowhere, fainting, having to sneak out through underground car parks – it was fascinating.”

These were the glory years of touring, as 1970s rock culture – “drugs and wild orgies” – gave way to the big business of the 1980s – “media, lawyers and sponsorship, when artists had contracts and had to turn up. It was very different. Tours became these gigantic money-making machines.”

It’s a testament to O’Regan’s charm that this shift “from rock’n’roll to big business” didn’t change the nature of his relationship with his subjects. Many became friends. But, since you’re always together, one recording the other, you are sometimes the only familiar face in a crowd of thousands. “It’s a pretty strange kind of relationship,” says O’Regan, “though there’s an intimacy there.”

At least, he adds, that’s the case with a solo performer. With a band, you need to be a master of interpersonal politics, and be careful to shoot each member equally, especially if you’ve been selected by one of them.

Keith Richards on the tour bus

Denis O'Regan

“It really is kindergarten stuff,” says O’Regan. “There’s a lot of rivalry. So many levels – with even the backing band members getting wound up by my hanging out with the star, travelling in their limo. And then there are all the affairs, the cliques that develop, those who really want to party and those that don’t. It’s a microcosm of society. It can be very intense. By the end you feel like you’ve been away for five years when you’ve only been away for one.”

Indeed, O’Regan says he feels like he’s packed several lifetimes into his time behind the lens, too. He notes that he’s coming up to the age at which Bowie died. “So if I live beyond that, great,” he laughs.

“It’s a different world now, moving through these decade-long phases, much like my marriages. It’s all about survival.”

For more info and to buy prints, see west-contemporary-editions.com