This winter, Goodman Gallery London presents Out of the Calabash (27 November 2025 – 14 January 2026), a major new exhibition by Winston Branch OBE – a painter who, at 78, is no longer simply overdue for recognition but rapidly becoming canonised as one of Britain’s greatest living artists. After decades of being spoken about as a “best-kept secret,” the art world is finally catching up to the scale, depth, and restless brilliance of his work.

Branch arrives at this moment with the full force of a late-career resurgence. His new paintings – luminous, abstract explorations of colour, light and space – come on the heels of his 2024 OBE for services to creative and fine arts, renewed international attention, and the jaw-dropping rediscovery of 20 lost figurative works in the summer of 2025.

For an artist who has spent a lifetime resisting categorisation, the current wave of admiration has been both vindication and invitation. As he puts it, with characteristic directness: “I told Nicholas Serota it was my time, and he agreed.”

A career that resisted the narrow boxes offered to him

Branch’s ascent originally began in 1960s London, where he emerged as part of the pioneering Caribbean Artists Movement alongside cultural giants such as Ronald Moody. Art historian Eddie Chambers notes that Branch “confounded and frustrated stereotypes of what a ‘Black artist’ should be producing” – a statement that rings even more sharply today as the art world revisits the reductive frameworks once imposed on artists of colour.

Born in Saint Lucia and sent alone to London at age twelve in 1958, Branch entered British life just as the country hurtled into the Swinging Sixties. He studied at the Slade School of Fine Art under Frank Auerbach, standing shoulder to shoulder with peers such as Maggi Hambling and Derek Jarman, and brushing shoulders with future heavyweights like David Hockney, Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland, and Patrick Procktor. Even then, he refused to be defined by race, fad, or fashion. “Everyone can see that I am Black,” he says. “I wasn’t looking for myself – I found myself at seven.”

It was during this period that Branch transformed a disused Battersea laundrette into his first studio. Though repeatedly rejected by the art establishment, his work quickly drew the attention of literary icon James Baldwin – a sign, even then, of the circles in which Branch’s vision was resonating.

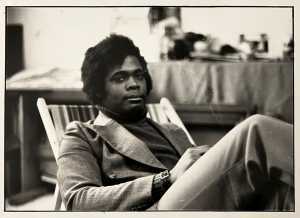

Winston Branch, London 1973

A Life Larger Than Any Movement or Moment

Branch’s story is also one of extraordinary cultural collisions. Named after Winston Churchill, raised in a devout colonial household in Saint Lucia, he has lived a life shaped by restlessness, chance encounters, and creative reinvention.

After early success in London, he decamped to Berlin and New York in the late 1970s, gaining a Guggenheim Fellowship and establishing international studios – before tragedy struck when unpaid rent led to his Berlin studio being cleared out. Years of work vanished overnight. “I felt my whole life was gone,” he recalls. Decades later, those paintings resurfaced in Greece, and Branch painstakingly restored what he could – recovering, among them, a portrait of “the mother of my second daughter,” a work especially dear to him.

The losses didn’t stop him. Nor did divorce, displacement, or the relentless churn of the international art scene. Branch simply kept moving. “There are a million reasons not to get out of bed,” he jokes. “I spent years being rejected daily. So what?”

From Saint Lucia to Berkeley and Back to London

In the 1990s, Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott invited Branch to create works for the National Collection of Saint Lucia, prompting a 14-year return to the island of his birth. Later, he served as a professor of art at the University of California, Berkeley, teaching painting and drawing while exhibiting widely.

Fifteen years ago, he returned to London – this time determined to cement his legacy in the city that shaped him. Today, his works sit in the Tate, British Museum, V&A, Brooklyn Museum, Legion of Honor and de Young Museum in San Francisco, and the Saint Louis Art Museum. Goodman Gallery’s announcement of global representation of Branch, in partnership with Varvara Roza Galleries, signals a new phase: one of institutional consolidation and public recognition.

Still, Branch’s ambitions remain characteristically unvarnished. His OBE, he says with a laugh, “didn’t mean much – I wanted a knighthood. I’m still working on that.”

The Man Who Writes His Future in Colour

Despite the decades, Branch’s energy remains electric. From his West London studio – alive with vast, colour-saturated canvases – he reflects on the long arc of his life with a mixture of humour, candour, and unshakeable perspective. “Everything has its time and season,” he says. “Nothing lasts forever. As Al Pacino says in Heat: ‘You must always be prepared to walk away.’”

Yet Out of the Calabash feels like a moment he isn’t walking away from, but toward. It is the culmination of a life lived in perpetual motion, unbound by category, geography, or expectation. It is also a reminder of what Britain almost missed: a painter of extraordinary lyricism, discipline, and cultural intelligence who has always been ahead of the systems meant to contain him.

Now, at last, Winston Branch is not just part of British art history – he is helping write its future.

Out of the Calabash at Goodman Gallery London 27 November 2025 – 14 January 2026. See ore at goodman-gallery.com