If you’re thumbing your slightly grubby second edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and wondering if it might be worth something, we have bad news. As big a phenomenon as Harry Potter is, you came to the party too late, and then foolishly folded the corners to mark your page. But how different the world of rare book collecting can be.

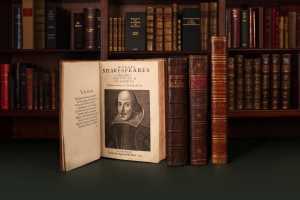

To cite the other extreme: Pom Harrington, of leading London-based rare book dealer Peter Harrington, last year contended with buying and then finding a seller for the motherlode. This was a First Folio – the first collected edition of 36 of Shakespeare’s plays, printing 18 of them for the first time and, potentially, saving them from being lost to humanity. Only 232 copies of the First Folio are known to survive, and most of those are with institutions or in museums. But Harrington has held one. It sold to a private collector for £6,250,000. That is one book you wouldn’t want to set your coffee cup on.

“A lot of people got into rare books over the pandemic, and that’s seen a flourishing of prices and a market that’s upbeat,” says Harrington. “We’re seeing books being rarefied. We’re seeing books printed in lower quantities now, but in higher quality, with some publishers producing the kind of books that encourage us to treat them more as art objects. But rare books have a quality all of their own.”

Naturally, while counterfeits are rare, being sure that such a book is what it claims to be requires expert oversight. But authenticity is not the only factor for collectors. Most important is desirability: “I can show you any number of rare 16th-century books that nobody is interested in,” chuckles Harrington.

And then there’s the condition: you want as close to the original, untouched condition as possible, with a torn dust jacket, or even a single missing page enough to make an otherwise valuable book more or less worthless. Counterintuitively perhaps, if the book has been scribbled in – by the author, at least – either as marginalia or an inscription, that increases its market value considerably. Take, for example, a first edition copy of Hemingway’s For Whom The Bell Tolls. Autographed, it might fetch £6,000; inscribed, £12,000; inscribed to someone connected to the author, £20,000; and inscribed to someone to whom the book is dedicated, £200,000. “But it’s all the same first edition book,” says Harrington.

Shakespeare's Folios

In a double whammy, Harrington once sold a copy of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities inscribed by Dickens to George Eliot, who would become another giant of English literature, for £275,000. And it gets better, at least for Harrington. He also once sold a first edition of Frankenstein for £300,000, but not just because the novel is considered the first work of science fiction. What made this particular book unusual was that it was, as far as can be ascertained, the one and only first edition presentation copy – one gifted by the author – from Mary Shelley to Lord Byron. “I can barely imagine a more amazing inscription for a 19th century book,” says Harrington. “It’s complete fantasy stuff.”

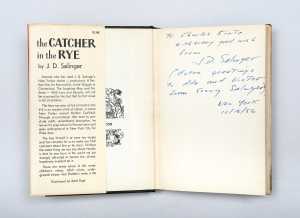

A presentation copy of 1951’s Catcher in the Rye – with inscription – is in his current inventory. What gives it the £225,000 price tag? The fact that Salinger was a recluse, and rarely signed books, and that he signs it with his nickname ‘Sonny’.

But then Harrington has also seen suspiciously too many books signed by Winston Churchill – even for that enthusiastic signer of books. Harrington explains that Churchill had a consistency of signature over time until he had a stroke in 1953 – “so beware a 1940s signature in a 1950s book”.

“Collecting books was for a long time perceived as something of a ‘gentleman’s pursuit’, but interest in rare books is thriving [among all sorts of people] now,” says Susan Benne, executive director of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America. Indeed, book sales are doing well despite – or maybe because of – the digital age. “Go to rare book fairs [in the US] and attendance has quadrupled over the last few years alone.” While at such fairs your first quality rare book may be acquired for as little as £200, this interest is certainly reflected in the prices.

“Prices have generally gone up, for the better items at least. And there’s much bigger demand now,” says Michael DiRuggiero, founder of the Manhattan Rare Book Company, in New York. This is not least because the internet has expanded access to the once rather rarefied world of rare book collecting, while also allowing for greater transparency in authentication and pricing (with a few frauds still taking in the gullible, of course). “The idea that a certain book is very rare is more easily exposed – online you can quickly see there are so many copies available and that it’s not so rare after all,” he says. “But then the internet also reveals what the market really doesn’t have available at the time, too”.

The Catcher in the Rye

But, he stresses, while there can be spectacular returns – one of his clients bought a scientific paper by Einstein for $6,000 and recently sold it for $60,000 – don’t make investment your first priority. Make it the love of books. “I know many collectors who buy what they think they should buy and aren’t happy with their collection,” says DiRuggiero. “And I find it’s much harder to sell someone on a book they don’t respond to emotionally.” Most people who get into collecting are drawn to a particular author or genre for personal reasons – childhood memories, nostalgia for their student days, because of their careers, travels or something they aspire to. “You can read a person’s biography through the kinds of books they’re interested in,” reckons Benne.

Besides, a return on the investment is not guaranteed, not least because the popularity of many books is subject to changing tastes generation to generation: Anthony Trollope is considered, by turns, a great novelist of the Victorian era and then an also-ran permanently in Charles Dickens’ shadow; other authors – Dr Seuss, or CS Lewis, for example – have seen their standing blighted, if temporarily, by politically correct concerns. DiRuggiero argues that while there seems to be a crossover between men who collect watches and those that collect rare books, the latter is, as he puts it, “never a flex. While it’s unusual for someone to buy one rare book – they get the bug, or at least I hope they do – invariably their books then become very personal to them,” he says.

Some will keep their books in what’s called a clamshell box, a custom-made display case designed to protect the contents from heat, sunlight and water – these factors aside, books are easy to keep, not spoiling like wine and very hard to sell on if stolen, though insurance for some tomes can be pricey. “But often these books are not displayed, and not shown to anyone. They’re an oasis; company with which to be quiet in one’s own thoughts.”

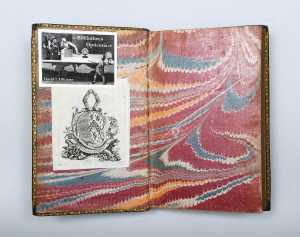

There is, however, a gilt-edged exception to the investment game – what those in the trade call the ‘high spots’. These are those books that, as he puts it, “are important to history, and which have become a permanent part of the culture”. These are the classics of literature – the aforementioned Dickens, Shelly or Shakespeare – or of philosophy, or in the way that Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687) – which outlined the first successful scientific model of the mechanism of the universe – will forever be important to science. The downside? There are believed to be fewer than 135 first edition copies of that. So these are not cheap to start with. Pom Harrington once sold one for £275,000.

Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica

It’s for this reason that Harrington’s personal holy grail would be The Whale – the title first given to Melville’s Moby Dick on its publication in 1851. “I’ve never owned one and that really annoys me,” he laughs. DiRuggiero’s would take the special offprint of Einstein’s 1905 paper on special relativity. But there are fewer than ten and each would likely sell for over $100,000.

But might there be investment potential for smaller fry? Benne notes the rising values of modern editions of classic novels – often appreciated for their graphic design – in a way that, she laughs, is leaving some old-school dealers perplexed: “People on the antiquarian side of the trade are like, ‘What? This book has increased in value because it has a certain dust cover?!’” And might there be some strategy in simply stockpiling first editions, taking on a punt on a new author becoming cult or winning the Nobel for Literature at some point?

DiRuggiero says good luck with that. “The reason books are often rare is because they were not thought of as important at the time, and so consequently very few copies were printed,” he says. “So you’d need the benefit of hindsight”. He speaks, by way of example, of that Harry Potter and The Philosopher’s Stone, which saw a first print run in hardback of just 500 copies, 300 which went to libraries – and so, inevitably, end up in poor condition, and all the more so for being handled by children. But if you’d had the vision to buy and preserve a copy? You’re looking at around £80,000.

Or maybe more. There are always the weird outliers. Three years ago a first edition of the same book sold at auction, the auctioneers describing it effusively, almost comically: “There is no other word for this copy but magical, incredibly bright and so very near pristine it’s surreal to hold. [It’s] obviously a beloved copy and serving as a sort of prophesy on a shelf as to what Harry Potter and his world would become”. The hyperbole worked. Someone, somewhere paid $471,000 for it. Wingardium leviosa, indeed.