So I’m killing time on YouTube and the algorithm brings a Business Insider video to my attention: Sword Master Rates 10 Sword Fights From Movies And TV. I’m a simple man. I clicked.

The video was sparse but effective: a clip was played, the sword master dissected the historical and technical accuracy of said clip, while supplying additional information of his own. “There’s this insane idea that longswords are really heavy, clumsy weapons,” he chided as the sword fight from the much-maligned James Bond film Die Another Day raged in the background. “They are not!”

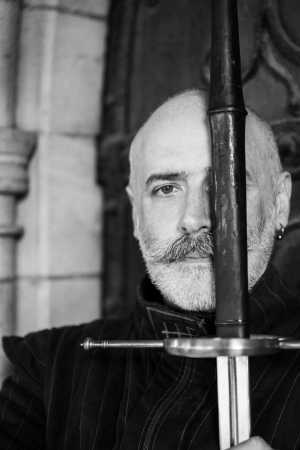

As with all such videos, the success rested upon the expert – and this guy was brilliant. He was bald, muscular, covered in tattoos and possessing a handlebar moustache of such magnificence it would have inspired envy in Wyatt Earp. He wore his knowledge lightly and delivered his critiques with a permanent twinkle in his eye, a university professor who moonlighted as a Victorian strongman. His cheerful introduction set the tone: “I’m a full-time swordsmanship instructor and today I’m going to have a look at a load of clips about sword fighting and slag them off hideously.”

The video had nearly ten million views. The comments were a veritable fanclub. “A swordmaster that looks like a swordmaster in an RPG.” “This man is exactly what I’d imagine an expert swordsman looks like.” “The guy: looks formidable and fearsome as all hell. When he talks: incredibly polite, eloquent speech.” “He has a moustache therefore I trust his opinion on the subject.” “The moustache is a thing of beauty.” “His moustache is capable of wielding a small sword in combat.” “His moustache alone has eight confirmed kills.”

His name was David Rawlings and he ran something called the London Longsword Academy. Its website proclaimed itself “the capital’s foremost fencing club of Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA).” Multiple weekly classes were held in Crystal Palace, Old Street and Canada Water. I phoned the number provided and a few weeks later I’m heading to Crystal Palace to interview one of the few professional swordsmen on the planet.

I loved swords as a kid. Spent the bulk of my pocket money buying new ones. My best friend and I staged countless duels in our respective gardens. Even now, aged 33, I still find myself absentmindedly cutting the air with a stick on a countryside walk. Hand me a cylinder of wrapping paper and I’ll probably attempt to run you through with it. Old habits and all that. And frankly, I think I’ve still got the moves. Were David Rawlings and I to cross blades on, say, a castle ramparts, I wouldn’t be so foolish to expect victory but I’d hope to hold my own long enough to jump into the moat.

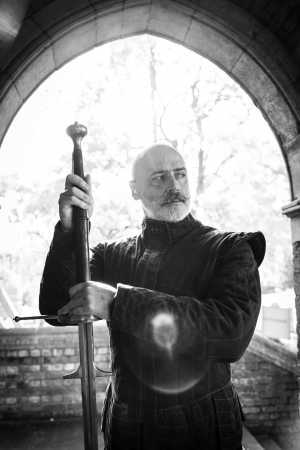

While Crystal Palace is short of castles, Rawlings taught classes in a vast Gothic church that made a great location for both a swordfight and a photoshoot. I went to his flat beforehand to carry some swords to the church. Any worry that he might fall short of expectations are dispelled the moment I walk into his kitchen. It’s crammed with swords. Longswords, short swords, rapiers, scimitars bristle along gigantic racks that take up half the room. There’s also the odd halberd, helmet and buckler – the man doesn’t discriminate on his weaponry. Should any reader wish to raise a levy, I know where to start.

A cutlass lies on the table in his living room. A cabinet displays a variety of knives and short blades. The numerous books on his shelves include The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship; Rules of Fencing; The Art of Combat; and The Way to Employ Arms with Certainty for both Offence and Defence. Another cabinet in the bedroom holds historical swords from different eras. On a bookstand, a magnificent illustrated hardback copy of Academie de l'Espée, a 1628 manual by the legendary Dutch fencing master Gérard Thibault d’Anvers.

Rawlings proves as polite and eloquent in person as he is when commenting on screen sword fights. After the shoot, he takes the photographer and I through a few simple guards. Each one is explained through simple visualisations: a low guard is ‘the plough’, a higher guard ‘the bull’ (think horns) and so on. We’re using rapiers, theoretically light, but after a few minutes manipulating the blade my arm muscles are aching; I understand why the man is built like a siege tower.

Enjoy the interview – if you’re reading the print version, feel free to roll the magazine into a cylinder and conduct a sword fight with the nearest mirror. It will nourish both body and soul.

Square Mile: How do you become a professional swordsman?

David Rawlings: You have massive amounts of hyperactivity! I did lots of martial arts as a kid. I have huge amounts of ADHD, which means I’m not very good at sitting still. I’m good at researching stuff. I have very, very good hyperfocus in certain areas; I can stick my head into a treatise that has an explanation of sword fighting techniques from the 13th century onwards, and I can cross reference that very well. And I’m very good at putting it into practice.

SM: Where did your childhood love of martial arts come from?

DR: I’m not sure. It’s just one of those things that some kids get into, particularly kids with hyperactivity issues; you tend to get put in classes that keep you active. I kind of never got out of that habit.

I’m always much more happy and much more meditative when I’m moving than I am when I sit still. And of course swords are inherently cool, and a gateway drug to other kinds of weaponry, so you end up doing all the things, with all the weaponry.

SM: How would you describe the London Longsword Academy?

DR: Fundamentally, it’s me and my students. Anyone who chooses to come and train with me. Currently, we have sessions in Crystal Palace, Old Street, and Surrey Quays. They put up with me taking small sums of money from them and offering my knowledge, which I update all the time. I research heavily, I train heavily. So the Academy is a combination of me and people who want to do swordplay, and be part of that great community.

SM: You taught a few guards to Lee [photographer] and me earlier, and you used simple terms to break each one down. The plough, the fool, the bull, the sky…

DR: Yes! It’s an interesting thing to me because these mnemonics change throughout history. And the value of those mnemonics is their use as a way of understanding what any particular author is talking about. There’s a tendency to go, ‘this is what everyone means by this’ – as opposed to going, ‘this is what a specific author means by this specific thing, which may differ slightly or greatly to another author using the same terms.’

The shape of the fool as a guard turns into the shape of the plough. Same shape but they have different meanings to different authors. We need to understand what those authors meant. I take the mnemonics that other authors have used; I use my knowledge of how those authors worked; and then I try to help you.

SM: While letting people occasionally hit each other with boffers…

DR: Not just boffers – steel, too. Hitting each other is very important. You learn something about how people are able to use force vigorously but politely against each other. Whenever you are training with somebody, you have to understand that there is a degree of courtesy in your partner because they’re not just smashing the living shit out of you. They are using courtesy to deliver blows at a measured pace.

You’re not trying to go much faster than the other person. You’re not trying to go much more forcefully than them. You are working within artificially imposed social constraints, which stops you from both injuring each other but still allows you to display skill. That skill becomes more mechanical, all levers and buttons, because you are not trying to bludgeon each other to death, you are trying to outthink each other using better mechanical and geometric understanding of the art.

SM: Like sparring in boxing?

DR: Yeah. It’s like point scoring as opposed to trying to knock someone out. You can always try and knock someone out but then you’ve got to consider how they’re going to progress through life. Are they going to have injuries which are going to affect them? Within the Academy, I give people a sense of how we can learn the skill while protecting our longevity as humans and to keep each other safe.

SM: Lifting those swords is hard work! It must be great for your fitness. That sword didn’t seem very heavy when I first picked it up but five minutes doing those guards, my arm was aching…

DR: If you do fencing well, then you form good connective tissue and good connective muscle structure. Rather than specific muscle structure that is suitable for one task. Because you’re maintaining extension of the weapon, you’re maintaining different positions of rotation, you’re maintaining balance. You end up creating something that is training the whole of your body.

It’s more like the muscle structure you’d expect from someone like a ballerina – where there’s a consistent chain of muscles always being supported. The whole of the body is being supported rather than very small isolated things. If it’s done correctly, it should increase your flexibility and it should increase your wellbeing overall.

SM: Simply picking up a sword gave me this sense of almost childlike joy. It took me back to playing in the garden with my best friend, or watching those swashbucklers on TV. It makes you feel like a kid again!

DR: Very much. And I think this is several things. It’s very important that we recognise this as being a form of a play. We’re not trying to kill each other. We’re trying to demonstrate skill. We were doing exercises yesterday where you could hear people laughing and it was a combination of reasons for the laughter. I’ve just discovered something cool; I’ve just made a silly mistake; I’m having so much fun right now. That’s what it should be.

This is a game. This is joyous. You can learn a skill. It could be a skill where if the bullets ever run out, then potentially it could save your life in that very, very unlikely circumstance. But it’s fundamentally something which is an amazing historical skill but also incredibly fun. You come from whatever job you do and you floss your brain. I’m just going to let myself go a little bit and remember what it is to move and be happy.

That rediscovery or maintenance of being childlike, I think is a beautiful, beautiful thing. It keeps you fit, it keeps you healthy, keeps you happy.

SM: When people first attend the Academy, is there anything that particularly surprises them?

DR: A couple of things. People very often say they don’t realise how complex this is. It doesn’t need to be complex, as you’ve seen. It can have a very, very simple base, but it’s something that you can learn for your entire life and still have more to learn. So there’s always something interesting. It’s very tempting for people to get into a mindset of going, ‘I have discovered how to do swordsmanship!’ And I know from doing this for 30 years, there is so much more to learn. And that’s its joy.

Every week, you can decide: I’m going to learn to move a little bit better. I’m going to learn to evaluate and reassess my ego and how I interact with other people and how I interact with my own successes and failures. I’m going to learn more information. I’m going to understand people from hundreds of years ago and the little nuances in how they think. It’s so similar to people nowadays and how we think. We’ve not evolved massively. We just have little social differences. We just have little mental differences.

The thing I’m really proud of is how many people have said they feel this is a safe space for them. Somewhere where they’re more confident being themselves and there’s not this pressure to be something. You get to be good to people. You get to be good to yourself and you get to be part of a community. That’s something I’m exceptionally proud of. Those are the two big things.

SM: Swords have been around for thousands of years. There must be so many books written across all these different historical periods and cultures. How many have you read, approximately?

DR: I’ve read lots. But with complete honesty, I have not read a lot of manuals cover to cover. I’ll read a certain section of a manual and then I’ll cross-reference with another section of another manual. I’ll be looking for specific pieces of information. There’s a lot of material out there.

SM: Is this a craft that nobody can ever master entirely?

DR: I would judge poorly anyone who says that. I have ‘master of arms’ as a job title, but I succeed and fail in every fencing session, I get hit by something, I learn something new. That’s the joy of it – because it’s only when you get hit that you can explore a potential solution. You want to encourage people to try different things.

I think the idea of mastery is a little weird. I like to think of mastery as being something where everybody tries to improve themselves a little bit. So if you can say that you’ve mastered yourself the day before, your next mastery will be improving on that day’s progress. I don’t like the idea of there being masters. I do like the idea of us learning to master ourselves over the years and then we die.

SM: Is part of you curious how you’d have fared 200 years ago with a live blade?

DR: I dunno. I’ve got enough scars and I don’t want to kill someone. The idea these periods are excessively violent is very much a misunderstanding. Obviously violence in culture goes up and down according to different societal stimuli, but I don’t like the idea that everybody used to sword fight all the time. It doesn’t make sense. However, I’d love to learn to fence with some of the people who wrote these books.

SM: Are there any specific books you would recommend?

DR: I’m reluctant to give a specific book and a specific author because the joy for me is seeing how all of the authors explain geometries which have massive degrees of overlap. They’re not all explaining specifically the same thing, but there is a vast amount of commonality between the range of movements that they are trying to articulate. I want to understand all of those things and I can’t do that by having a structurally favourite thing because otherwise I’d keep going back to that thing to the exclusion of other things that might influence and increase my knowledge.

I have manuals that I study more than others. So Tuesday for example, will be Gérard Thibault d’Anvers. So I’ll spend a vast degree of time looking specifically at Thibault, but then I will look at Francisco Lorenz de Rada, I’ll look at Luis Diaz de Viedma, I’ll look at Luis Pacheco de Narváez and I’ll see how those things combine.

SM: If you could go back in time to train with one person, who would you choose?

DR: I don’t know. Would you have the same joy of training with somebody as you would reading their condensed information? Because the advantage of having a book is you have the sum of somebody’s knowledge condensed.

Probably Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Mozart is the white Chevalier. He’s an absolute virtuoso. He’s a violinist, he’s a composer. He’s an absolute dandy. He’s a small-sword genius. He’s around at the same time as Alexander Dumas’s father. They even fenced together at some point. They’re fencing at a very interesting point of history. They’re fencing with Chevalière d’Éon – there’s this overlap of these three wonderful characters. That’s somebody I would’ve dearly loved to have found.

SM: Do you have a rough estimate of how many swords you own?

DR: Not enough! There is a simple equation that my friend uses to describe how many swords is the correct number of swords. Quantity of swords plus one.

SM: You’ve rated a lot of cinematic sword fights on YouTube. What’s the best?

DR: The Princess Bride, obviously! Not because of the sword fighting content. The sword fighting content is pretty terrible. It’s not a good fight scene. But as a representation of how authors wrote about each other, it’s absolutely fantastic.

There’s a passage in Pacheco where he’s discussing a move. Basically, you take a sword down, you take a sword that’s above your sword, knock it to one side, and then you stab someone underneath. He spends about two and a half pages explaining why all these other authors fundamentally don’t understand the technique. The idea of slagging off all these different authors is what The Princess Bride gets so right!

So one of them goes: “I find that Thibault cancels out Capa Ferro, don’t you?” And the other replies: “Unless the enemy has studied his Agrippa…” It’s perfect! I’m showing that I am more educated than you and these experts who are very good in their way, but not as good as me. It is an absolutely wonderful, wonderful analysis of literary bitching.

SM: How many sword fighting techniques are there?

DR: It really varies. How long is a piece of string? Or a blade! Every single form of sword fighting is constrained by the physical limits of the human body. And that varies between different people. So different people have different reach, different people have different mobility, but they are all constrained by their reach – unless they throw the sword but they usually only get to do that once.

La Verdadera Destreza is a very interesting system because it’s incredibly geometric and it expresses itself in a very complex way. It gives the impression that it’s something posh and greater than – what I suspect is – normalising posture that accompanies the mindset of: ‘if you are shitting yourself, you are more likely to hold your sword out very straight because you are scared. Right, let’s learn to fence from there.’ Whereas other systems have a lot more variety because you can move from different positions and they want to include the full range and expression of potential ranges of motion.

SM: Holding the sword straight felt quite natural. Other postures, less so.

DR: Every posture has its advantages and limitations. The arm-extended postures control the centre, offering offence and defence directly, but they offer the opponent your sword to work against and leverage if their arm is shortened.

Conversely if your sword is withdrawn you offer your opponent less to work with and gain leverage, but it becomes easier to make you widen your weapon – open more on one side or the other.

SM: Are sword fights in movies ruined for you? You’ll see all the mistakes!

DR: No, I used to work in a photo lab for a number of years. You can go to a movie and think, ‘Ah, that’s a bit too yellow.’ But after five minutes you don’t worry about it.

Although I’ve not seen the Chevalier movie because I’m so invested in Chevalier being an amazing fencer – if the fencing is a load of dross, I’m going to be really upset. But if I see a fantasy film and the fencing is fantastical, I don’t care. It’s got dragons in it! You suspend disbelief. When we are playing around, we are not really sword fighting. It’s not real. We’re having fun!

SM: Would you like to work in film?

DR: I’d like to inform a film crew or a director on how to do things historically accurately. There are some very, very good choreographers out there, but that’s something I would like to access. I would like to give them the benefit of that knowledge – and also I’d like to do it because it’s cool.

I’d like for more people to realise how historically diverse this discipline has been and how it should be diverse going forwards. Look at the different array of people who did this. Look at the people who are good at this. It’s not confined to a white, cis male paradigm.

That’s what I want for the Academy going forward: more diversity, more people feeling welcome to do it, more people feeling invested in doing it.

And I’d like a crown. A crown, a throne and lots of money to buy more swords.

View on Instagram

See more at: londonlongsword.com