Forever young, I wanna be forever young. Who doesn’t? Sadly, eternal youth remains a pipedream (I just know they’ll crack it when I’m on my deathbed). However, aging well has never been more attainable – or more important. Modern medicine has done wonders for extending life expectancy but the quality of that extended life is a much more subjective matter.

Like many people no longer quite as young as they once were (33, if you must know), I’ve long mused on the state of my physical health and its implications for later life, without ever quite getting round to acting on these musings. Most of my twenties were spent hitting it hard, and I can only partially blame my chosen career (I literally review cocktail bars) and social dynamics. Anyway, your health doesn’t care about the justification. Your health suffers regardless.

And then I received an invitation to experience The Longevity Doctor, a pioneering new health clinic that has just arrived on Harley Street. It’s led by Doctor Philip Borg, an American board-certified physician in anti-aging and regenerative medicine. Dude knows his stuff, essentially. The programme? An extremely detailed assessment that will both take a snapshot of your current health and map its future development, minimising potential risks before they can happen. Like Minority Report for your small intestine.

Ahead of visiting the clinic, I’m emailed a cognitive assessment – memory games, essentially, six of them that take around 20 minutes in total. Match the symbol in the box, specify the order of the numbers – that kind of thing. These games are surprisingly fun and very frustrating. You’re doing well until you aren’t. Errors often arrive consecutively, the second the result of lapsed concentration while bemoaning the first. Maybe that’s part of the assessment.

Full transparency: the day before the test I am, to use non-medical terminology, shitting it. (Not literally: that might pose a problem.) Every big weekend, stag party, music festival, the entirety of my university degree, all crowd my memory, not so much the ghosts of Christmas past but healthy future. Christmas – that’s another one. The lifestyles of dearly departed grandparents are mused upon at length.

Dr Philip Borg

The day itself proves remarkably enjoyable. I arrive at a rather grand building on Harley Street that feels more like a country house than a hospital. Everyone is very friendly, from the receptionists to Elaine the patient concierge who leads me to the waiting room and offers refreshments when appropriate (i.e. after my body scan). Install a jacuzzi on the downstairs floor and you’ve basically got a spa.

The tests are all extremely advanced and clever so you’ll forgive me discussing in layman’s terms – if you want a more scientific breakdown of what everything does, the website will happily oblige. First up, I get my blood pressure and weight readings from Emma the lead nurse. She then takes blood samples for further testing – nothing that you’ll miss – and installs a glucose monitor on my arm to measure blood sugar levels for the next fortnight. So far, so good – although the glucose monitor requires linking to an app, like everything in the modern world.

Steven the bone density technologist then measures my bone density. (As you might have guessed.) This is very quick and painless; Steven scans various parts of my body and the results appear almost immediately. Not only do I see my current bone health but also a chart mapping how my bones will progress over the coming decades. Happily everything is nice and dense: by the age of 100 there’s a decent chance I’ll fracture my spine but cross that bridge, etc.

The writer gets his bone density scanned

Onto the consultation with Dr Philip Borg, the founder of The Longevity Doctor. He’s a very impressive fellow, with the physique of a former athlete and the smoothness of a Swiss banker. Dr Borg explains the mentality of the programme is prevention rather than cure. “I felt like I was getting patients at the wrong stage of their journey,” he says. He talks of fighting battles that could’ve been avoided. The vast majority of later-life ailments and diseases can be traced back decades. “The heart attack that kills you at 70 started at 30.”

It’s not just the quantity but the quality of life that concerns Dr Borg. “Nobody wants to live to 100 having spent their past 15 years in bed, incontinent and not mentally present.” Fair point. Obviously it’s impossible to map the future precisely, offering risks as exact percentage: drop that cigarette else there’s a 45% chance you’ll be gone by 60. But make the right decisions and you should reap the longterm rewards.

He supplies some helpful pointers. Apparently oral health is linked to Alzheimer's so floss daily, brush twice a day, and visit the dentist every six months. Even in milder climates, apply sunscreen at least once a day. (Dr Borg has extremely good skin.) Zinc sunscreen is the best; he suggests EltaMD. The circumference of your waist is a big predictor of cardiovascular health: aim for less than half your height in centimetres. (Gulp.) Practice mindfulness such as breathing exercises, meditation. It’s not stress that kills you but your reaction to that stress.

Someone who definitely isn't the writer gets her body scan

Even by the standards of modern technology, the body scan is incredible. I lie in a dark room while Dr Borg scans down my body with what I can only describe as a magic wand; within a few seconds, detailed information on my internal organs appear on a computer screen in front of him. The scan reveals I’m basically fine but I do have a fatty liver; the optimum liver fat is 5% and mine is, let’s say more than 5%. Again, the excess fat around the waistline is a big giveaway here: no wonder the good doctor raised an eyebrow when I estimated my weekly alcohol consumption. Right now, it has no impact on my quality of life. In 20 years? That’s another matter entirely.

A fatty liver is hardly surprising: I had a fairly hedonistic twenties and although my thirties are far tamer, the pub is still the epicentre of social life. It’s not just booze: diet is also a major factor. (Having both my local and one of London’s finest pizzerias within two minutes’ walk of my flat can be considered suboptimal.) I’ll say this: there’s a huge difference between knowing you should lead a healthier lifestyle, even grimacing before the mirror as you prod the belly flab, and hearing the consequences of said lifestyle read out as a literal percentage. Sobering stuff, for want of a better word.

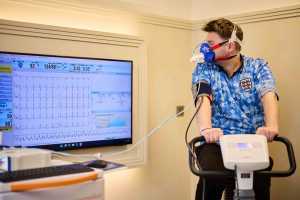

Finally, the fitness assessment with training director Jon Roberts. Balance, mobility, core strength are all measured. I push up, I jump, I balance on one leg. Most excitingly, I mount an exercise bike and don a Bane mask, various tubes attached to my chest to monitor my cardiovascular readings. Then I pedal until I can pedal no more, with the resistance level rising every minute. This one goes quite well: anything over level 12 is considered a very good stint and I nearly breach level 13. Physical fitness has never been an issue, one of the reasons I never worried too much about the expanding gut.

The fitness assessment is very Bane

The day is finished but the assessment continues. A few weeks later, I’m emailed a detailed breakdown of my many assessments, including the blood tests and glucose monitoring. (There are a lot of graphs.) Every patient also gets a virtual consultation with Dr Borg to discuss these results and how they should be acted upon. In my case, the prognosis is simple: lose the belly flab and reduce that liver fat. Dr Borg recommends I get a Whoop to track my health metrics and several supplements from Healf to boost my physical and mental performance. He says solid progress can be made within six months and suggests we catch up in September to see how I’m doing. The journey to a better me has begun.

I can’t overstate the importance of the second consultation in both explaining what everything means and charting a path forward. Luckily for me, liver fat is easily reduced: cut down on booze and junk food, exercise regularly and eat yer greens. Simple stuff but would I have ever got my act together without the assessment? Honestly, I doubt it. I don’t needn’t transform my lifestyle, simply tweak it a bit. Do the stuff I’d meant to do for years but never quite found the incentive. Short-term, I’ll greatly increase my chances of being cast as the next James Bond; long-term, I may yet thrash my grandchildren at tennis.

I'm here for a good time not a long time is a mentality that sounds cool at 25 but will be much less palatable in your 50s. Thanks to The Longevity Doctor, why not do both?

For more info, see The Longevity Doctor