Charlie Casely-Hayford laughs when I ask him whether fashion is objective or subjective. On one level, this isn’t surprising: Casely-Hayford laughs a lot, frequently at the absurdities of his industry, sometimes at his own quirks and foibles. If you were to solicit the characteristics most commonly associated with the average fashion designer, I dare say a sense of humour mightn’t occupy the upper echelons of the list. But then average is not a characteristic you would ever associate with Charlie Casely-Hayford.

Over the past 15 years, Casely-Hayford has established himself as one of the leading names in British fashion. He was 22 when he co-founded the Casely-Hayford brand with his father, the legendary designer Joe Casely-Hayford. Theirs is a high-achieving clan, excelling across law, broadcasting, history and journalism. Casely-Hayford opened a store on Chiltern Street in 2018; a few months later Joe passed away of cancer. Charlie has spent the subsequent years “trying to carve out my own space in a manner that I’d hope he would still feel proud of”.

I first met Charlie in early 2017. He was one of my earliest profiles for Square Mile, and I remember feeling daunted by the thought of interviewing a fashion designer – who would surely run the gamut between aloofness and utter lunacy. More fool me. Charlie was a joy: thoughtful, eloquent, cheerfully aware of the perception of fashion and a world beyond it. He even emailed his thanks for the interview.

For the sequel, we planned to speak at the Wallace Collection, a short walk from the store and a favourite haunt of Casely-Hayford. He’s a lifelong Londoner, growing up in Shoreditch, now residing in Archway with his wife, the interior designer Sophie Ashby, and three children.

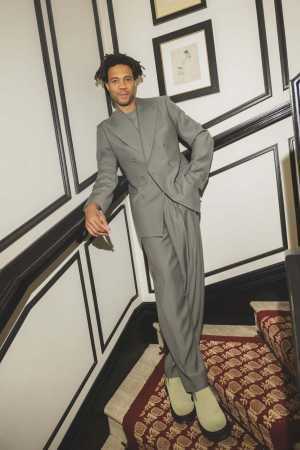

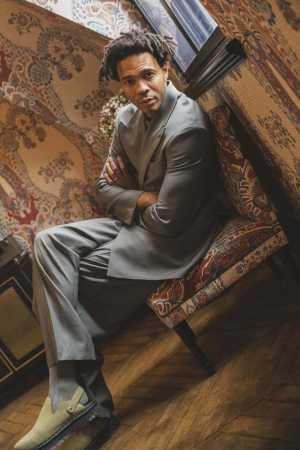

The gallery’s packed café meant a swift relocation to Durrants Hotel down the road. Over the eight years (!) since our previous interview, Casely-Hayford has accomplished much, not least the total cessation of the ageing process: he could pass for a decade younger than 39.

Earlier this year, Charlie was invited to design Edward Enninful’s outfit for the Met Gala, and attended the event himself. The theme was ‘Superfine: Tailoring Black Style’; the accompanying exhibition showcased the work of influential black fashion designers – including Joe Casely-Hayford. It seemed an obvious entry point…

Square Mile: Let’s start with the 2025 Met Gala. Talk us through that experience…

Charlie Casely-Hayford: Where to begin? So the Met Gala came about quite last minute, as is often the case in fashion. We were just given this incredible opportunity by Edward Enninful to work with him on his look for what was such a significant Met Gala and theme.

We created a beautiful bespoke piece that had a lot of history and undertones of the history of menswear tailoring, but there was a modernism to it, which is I guess our handwriting anyway. I was kindly asked to attend as well, which was a very surreal experience. And we had a few of my late father’s pieces in the exhibition.

SM: That sounds like a proud moment.

CCH: Yes, it was very personal and certainly emotional to see his pieces in that exhibition. If I think of everything he had to go through in his career. To get to where he did in the 1980s and 1990s, when the climate and landscape were certainly different to my personal experience in the fashion industry. It was wonderful to receive that acknowledgement.

We have most of his archive. He started designing in the mid 1980s, 40 years ago now. And a lot of the pieces still feel very relevant and current. We’ve had quite a few people asking if the pieces that were in the exhibition are available to buy. It was definitely a career and personal highlight.

SM: What’s the actual evening like?

CCH: Very surreal. So I got out of the car and it’s wall-to-wall PRs on either side. You walk straight by them and you are greeted with those famous steps and there’s a hundred paparazzi on either side. Someone says, ‘stand there’, you’re blinded by the lights, then you move to the next spot and you’re blinded again. I came out at the same time as Pharrell. They double you up.

Got to the top of the stairs, wandered through; I remember wanting to pop to the loo! Anna Wintour was at the top. Her assistant whispered something about me in her ear. She said, ‘Oh Charlie, thank you for coming down; so happy to have your father’s pieces in the exhibition.’ So that was a nice start to the evening.

SM: A lovely start! How do you pass the rest of the evening?

CCH: It’s a weird one because it’s very strict. You can’t bring anyone, you can’t bring your other half. But there was quite a strong British collective. I worked with Sam Smith back in the day, and spent my youth with Callum Turner. I hung out with them for most of the evening until we sat down for dinner. Then Usher and Stevie Wonder performed, which was quite something.

SM: Let’s go back to the start of your journey. When did you realise fashion was a path you wanted to follow?

CCH: I remember from a relatively young age, maybe 13, having a conversation with my dad. In no uncertain terms he told me there was no way that I was going to go into the fashion industry, I think because it’s such a challenging industry to succeed in. It’s so seductive, a lot of people want to work in it, but very few people make it.

My parents [Joe and Maria] met at St Martins and started their label soon after. They worked crazy hours, many sleepless nights. Some seasons it was fantastic. Other seasons, if you got a bad review, it was really up and down. I think they were both nervous about the prospect of my sister and I going into that world and having to face the same challenges that they had.

I don’t to this day know if it was reverse psychology or if he meant it. I also went to St Martins. Outside the classroom, there was this wonderful spectrum of identities being formed and people expressing themselves with their clothing.

I became fascinated with the power of clothing and what it can do in terms of perception, empowerment. It can do so many different things. It can make you feel invisible if you want to hide. It can bring you to the fore if you want to be centre of attention. It’s such a powerful medium.

I’ve never been interested in fashion in the literal sense. I’m more interested in identity and how clothing can help to define, shape, and aid one’s sense of self.

SM: Can you remember the first person who made you aware that clothing is more than just a garment?

CCH: I couldn’t name the person but I do remember very specifically having that feeling at Central St Martins. As is often the case for young people, I was still figuring out what I was about and who I was. I’d get dressed and I’d consider what I was wearing. I became more and more interested in how what I was wearing might be perceived by other people.

It felt like a very organic move to start working with my old man. We started the brand together in my final year.

SM: You loved music as a teenager, right?

CCH: Yeah. I had a very, very deep relationship with my old man and he dressed a lot of musicians throughout his career. He was heavily into music. Growing up in my parents’ studio in Shoreditch, he had this huge space behind his desk that was floor-to-ceiling vinyl and CDs. A real spectrum of genres as well. Both of my parents were interested in everything – we’d often go to the ballet at the Royal Opera. That was my mum’s passion and my dad was really into it as well.

Dad bought me my first Wiley album; he was into grime. He was always interested in growing and learning; also this idea of unlearning. It’s a common misconception that because he was the more senior out of the two of us, he brought the classicism – actually, it was often the other way around. A lot of the innovation came from his side.

He was like a sponge; he was malleable; he was interested in looking at things from different perspectives. He wasn’t set in his ways as his career progressed.

SM: Is that something you try to emulate? The process of unlearning?

CCH: Yeah, yeah, it fascinates me for sure. It’s something we incorporate very subtly into the brand as well. Dad always put it as: “an army of individuals”. That’s how he wanted our clients to feel.

We weren’t creating such a strong handwriting that’s the same anywhere, it’s never really been our way of doing things. It’s more about creating a language where when someone has a strong sense of self and there’s an internal confidence – that’s our language. It’s like a nice space where we create pieces that are modular and work with each individual to help them develop their own personal style.

SM: Did you have a mission statement when you started in 2009?

CCH: It was never like that. The easiest way to describe it was like a conversation between father and son. Just chatting. We never spoke in fashion terms. A topic would come up, generally around culture or the arts. That would evolve and naturally we would be able to utilise a concept or the language around it to inform our thinking and the design. That was how we worked together. It was how I got to know my old man as well – through the design process.

SM: Working with your dad, presumably you felt like a junior partner. Was there a moment when you felt like you’d arrived?

CCH: He never made me feel like my comments weren’t valid. But I have such a great respect for him, there was always a sense of hierarchy even though it was very important for him that we were equals. I enjoyed the dynamic being like that. It allowed us to create this transgenerational language through our clothing because we wanted to create garments that would appeal both to someone my age and his.

This idea of dressing your age, it was irrelevant for us because we were trying to create timeless pieces that someone could wear 20 years from now. A good example is the Met Gala, being asked by so many people if the pieces are available. They were made in the mid 1980s.

SM: I interviewed the boxing promoter Eddie Hearn who followed his father Barry into the family business. He was obsessed with trying to outdo his dad. It sounds like you had a different mindset…

CCH: No, I totally understand that, and I have always been conscious of going down that path. I made quite a big decision when he passed away. Rather than attempt to emulate his career, I would carve out my own path – which is why the brand shifted more towards tailoring than our previous incarnation as a fashion brand.

He’d achieved so much in his time, I didn’t really need to try and compete with that. And so I’ve been trying to carve out my own space in a manner that I’d hope he would still feel proud of. That’s been my day-to-day goal.

SM: Tell us about the shift to tailoring…

CCH: Made-to-measure tailoring is what we are best known for. My dad was creative director at Gieves & Hawkes before we started the brand. Our DNA is built on the traditions of formal tailoring, but we also have the scope and understanding to explore more interesting silhouettes if our clients desire. I love the spectrum of clients that we get through the door. We make a lot of work suits for guys in the City but we dress a lot of artists and musicians. It’s not like I enjoy one more than the other.

Some people will have a remit, a lot of people will know the purpose of the suit but they won’t know exactly what they’re looking for. It’s my team’s job to draw that out of them. People don’t necessarily have the language, which is totally understandable, and they are intimidated by the process. We try to create a warm, intimate environment so that you feel at ease. It’s a journey. It’s fun! Clothes should be fun. They don’t have to be serious. It should bring joy to put a garment on.

SM: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in the industry over the past 15 years?

CCH: The peaks and troughs in the fashion industry are quite severe. There was a real London menswear moment when we started to show during London Fashion week around 2015. There were some really talented designers coming up, everyone knew each other. London was getting a lot of international recognition.

There are these five-year cycles. Fashion is such a challenging industry as a designer if you’re independent because cashflow is a total nightmare. And so five years generally is a time at which you either close up shop or you are moving on to the next level. A lot of brands couldn’t keep the momentum going because the period from where you invest into your collection and when you actually get the return, it’s just so extreme. Most people can’t maintain it. Unfortunately, that whole moment died out, and a lot of brands went under.

In the last five-to-six years we’ve seen the emergence of the next generation. The momentum seems to be greater. I’m a huge advocate for the talent we have in the UK. A lot of my peers and friends, this might be the first time where there’s actually a sustained momentum and we can build on it and create something that will stand the test of time. Everyone looks at my dad’s generation, whether it’s Paul Smith or Margaret Howell or Vivienne Westwood, and it’s very hard to achieve that nowadays. It’s a different world, the wholesale market’s completely fallen apart. The game’s completely changed.

SM: Has social media affected it?

CCH: Yeah, massively. It’s given a lot of my peers the tools to create businesses on their own terms. When I started, wholesale was king and your business was defined by the big retailers, whether they thought you were the flavour of the month. A lot of those retailers have gone under, and they took quite a few brands with them. It’s a challenging time in that sense.

SM: It feels like there’s been a pushback in terms of immediate consumer culture. I do think that quality ultimately prevails.

CCH: Fashion by definition is based on transiency. It’s very hard to stay relevant for 20, 30 years. I’m happier in the space we’re in because I’m not creating clothing for the sake of it. Fast fashion has created such an issue with how the general consumer perceives clothing, and also diminished the value of the currency of clothing.

We do everything we can to make sure that our customers engage with it in the opposite way. A lot of that comes down to collaboration, a lot of our pieces are custom made. We like this idea that the customer comes along the journey with us. When they put on the piece, there’s already a memory there.

SM: Tailoring can be quite intimidating – there are a lot of rules. Are there any rules that you agree with, and any rules you consider to be complete nonsense?

CCH: We don’t necessarily think about it in such stringent terms. What I enjoy about menswear is it’s all in the details. There are, as you say, a lot of rules. The space where you can innovate is often smaller than in womenswear – but it’s more exciting because the smallest detail can have the biggest impact. We don’t break rules for the sake of it. We approach it more as problem solving. What would our man want to wear in the future? Try to create pieces that he doesn’t necessarily know he wants to wear.

I remember someone saying to me at one of our early shows that they always come to our fashion shows because the way our pieces were put together and styled every season, it was just far enough away that it would force him to evolve his style. He felt like he was always moving forward but it wasn’t so far removed that it felt intangible and unrelatable.

That stuck with me. My dad always believed this idea that classic or timeless doesn’t mean standing still. There needs to be a sense of evolution.

SM: Do you get inspiration from non-fashion influences?

CCH: I think all of my inspirations come from outside of fashion!

SM: Can you give a couple of examples?

CCH: For art history, I studied neoclassicism and classicism. That still informs my thinking day-to-day in terms of colour, palette, composition, structure. When I think about architecture, how elements of a building are put together, I think about the human form in the same context. I know that sounds super airy-fairy!

SM: Does music also inspire you?

CCH: Yeah, I’m heavily inspired by music. Generally it’s not just high culture, it’s low art forms as well. Definitely a strong impact on me. I like the idea of moving between high and low because I think that’s how people dress anyway.

SM: Like wearing trainers with a suit? Although do trainers count as low fashion?

CCH: They’ve been absorbed now. Occasionally you have pieces of clothing or accessories that maybe start out as a trend and then they move into the canon. That becomes the tradition and then you can build on that.

SM: Do you have any traditions or techniques when designing a garment?

CCH: It is quite often problem solving. So if I’m walking around London and I keep seeing the same things… all these guys are wearing X and actually what they need is Y. Then I start thinking, ‘OK, how do we create it so these guys who are wearing X can transition over to Y?’ Enhance their outfit and their sense of self. I think about it in those terms. It’s not, like, ‘Today we’ve got to design five jackets and four shirts.’

SM: You’ve worked with some massive names. Any stand out?

CCH: That’s a hard question. The people I’ve most enjoyed working with are Stormzy and Cillian Murphy. I’m a big fan of how they roll through the world. I’ve got great respect for Stormzy as an artist, but also everything he does outside of music for community and cultures. Cillian Murphy, I’ve always been a huge fan of his work and I like the fact he keeps to himself. It proves that you can do that if you want to and still be very successful in your art.

When I first started, the music was such a big thing for us. We wanted to work with the best up-and-coming British musicians. We’ve never done any formal marketing, we never reached out to anyone. But we ended up working with The xx when they won their first Mercury Award; James Blake when he got his first Grammy; Sam Smith when they got their first Brit.

The styling game now is such a big business. Often celebrities are paid; it’s a different game. We still dress a few people here and there but we like it when there’s a personal connection. We worked with Theo James a lot before The Gentlemen came out and built a really nice rapport with him.

We get asked a lot to dress people, as I assume a lot of brands do. But it’s completely transactional. You send them clothes and they might happen to pick you out of the forty garments they’ve been sent. I’d rather work with six people every year and know we’ve done it on our own terms.

SM: What has surprised you most about your career to date?

CCH: I haven’t become jaded by the fashion industry. It’s quite a mean industry, and there’s the fickleness of it as well. A lot of the time you are trying to sell things to people that they don’t actually need by creating a sense of desire that they need to be better or look better. That’s why they need to buy your garments.

SM: Like that Coco Chanel quote…

CCH: “Luxury is a necessity that begins where necessity ends.” Which I think perfectly sums up what I’m trying to say. But every day when I come into work, constantly my neck is like an owl because I’m just looking at everyone. I love what people are wearing and I’m so excited.

SM: Do you stop people in the street?

CCH: I would love to! I chat about it with my wife quite a lot but I’m always concerned about how it might come across. I see so many greatly dressed people, and I don’t necessarily mean fashionable: I love people who’ve got their own thing going on, their own style. It fascinates me. ‘How have you made those decisions to wear this today?’ It doesn’t matter where I go in the world, my neck is always crooked. I feel like every day is almost my first day because I’m seeing stuff for the first time, all the time.

SM: Not many people have a vocation that’s literally everywhere…

CCH: It is on my mind the whole time – even if I’m in the gym, I’m looking at people. When I was a kid, my dad and I used to play this game where you’d guess what someone’s wearing on their bottom half by what they wore on their top half. Occasionally I still play the game by myself!

A lot of people fall into categories. It’s painful to know that we’re all so clichéd but most of us want to fit in. You adopt a tribe and you adopt the visual language of that tribe. A few people choose not to – the innovators. But most of us want to fit in.

SM: Do you play the ‘guess the outfit’ game with your kids?

CCH: [Laughs] No, no! I’m in a difficult situation with my kids. I love the idea of having a third generation business but I don’t put any pressure on them. If they show interest, obviously I’d love that, but I’d never put any pressure on them to follow in my footsteps.

SM: What advice would you give to aspiring designers?

CCH: It is quite a lonely pathway. If you decide to start your own business as a designer, the network’s quite closed; I know a lot of people who really struggled with that. It’s not like a sharing community until you get to a certain level.

We set up a scholarship in my father’s name with the British Fashion Council a year ago. One or two recipients each year receive funds to help them get through university, and I do a one-on-one with them throughout the year. The last one was really interesting. The talent level was so high, and every single person used the same word: ‘community’. They didn’t see themselves in isolation. They saw this idea of building a brand as community-based and they loved this idea of collaboration.

Back when I started, we were all a bunch of individuals. I was friends with pretty much everyone on the scene but everyone was grafting in their own name. This next generation might be more collaborative and therefore create a more positive mental outlook. Being a designer is quite a lonely path, and it’s an odd one. You are creating something that is hopefully worn by a lot of people but you are often doing that in a closed environment with a few other designers in your team.

My dad encouraged me to experience different elements of a fashion brand and work at other places. So I was fortunate enough to work at Dover Street Market for several years, which I considered to be my PhD in fashion. I was on the shop floor. It’s really important to understand the commerce of clothing. Quite often as a designer, you design something in your studio; you have a sample made; you go to fashion week; you do a runway show; you go to Paris; you sell the collection; it goes into Selfridges; someone buys it; you never see the person who buys it.

You go through this whole thread and you never experience the final part of the journey. There’s this disconnect between you as a designer and the consumer. It’s important to have that experience, whether it’s on a shop floor or anything like that.

View on Instagram

SM: When you’re looking at people around town, what are the most common mistakes that you see?

CCH: OK, a really basic one. When guys want to dress smart casual, they often take a suit jacket and pair it with casual garments, whether it’s jeans or chinos. And they basically split up their suit and put the jacket on. It needs to be intentional – find a jacket that is made specifically to be worn in conversation with more relaxed pieces – rather than taking your actual suit jacket and pairing it with casual garments. It’s incongruous and it doesn’t flow in a way that it could easily if you invested in more of a modular wardrobe. Find pieces that work together rather than trying to force pieces together that don’t.

SM: What jackets would be better?

CCH: Traditional Italian-style jackets have a softer shoulder construction so they lend themselves more to casual dressing. If you’re pairing trainers and a T-shirt with your suit, I would opt for a soft-tailored garment rather than a structured garment, They’re different languages. Before lockdown, the suit was considered its own language – a separate entity worn when you needed to dress up. Post pandemic, it’s been integrated into the day-to-day, but you still must give thought to how that’s done.

SM: Is fashion subjective or objective?

CCH: [Laughs] Well, what I love is that fashion is not monolithic. It is a deeply woven tapestry of different strands. What’s beautiful to one person may be ugly to another. There’s not a huge sense of practicality to fashion. That’s probably the difference between fashion and clothes. Not the only difference but one of them.

Square Mile AW25 Issue

Square Mile AW25 Issue

Square Mile AW25 Issue

Square Mile AW25 Issue

Square Mile AW25 Issue

Square Mile AW25 Issue

Square Mile AW25 Issue

See more at casely-hayford.com