Twenty five years; 26 books; 49 languages and more than 100 million copies worldwide, Jack Reacher has become a global phenomenon by any measure. And that’s before you count Tom Cruise’s brace of blockbusters bringing in $380m at the box office.

British novelist Lee Child has seen his creation grow beyond his wildest dreams – a marked contrast from the humble beginnings of his first Reacher novel, which he wrote by hand, unable to afford a computer.

The latest incarnation of the famous drifter is Reacher, a new Prime series that’s bringing the story to an even larger audience.

Just three days after Prime premiered the series, the company renewed Reacher for a second season.

The show has shattered viewership records and within 24 hours of its debut was ranked among Amazon’s top five most-watched series ever – in the US and globally. It is also among its highest-rated original series to date.

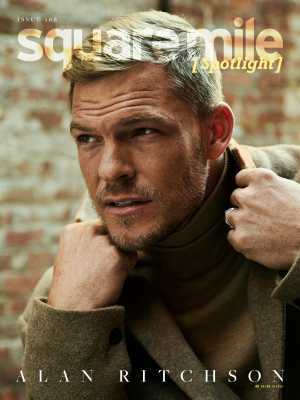

We asked Lee to interview the star of Reacher, Alan Ritchson. The chisel-jawed ex-military brat is the perfect physical embodiment of the protagonist, Jack. But what does it take to play a character that is already known and loved by so many?

The interviewer often becomes the interviewee in this illuminating conversation. Enjoy the read – and if you’re on the go, listen to the full chat via our podcast below.

Lee Child: Let's start at the beginning – where were you born?

Alan Ritchson: I was born on a cold, blustery day in Grand Forks, North Dakota. My dad was in the military so we moved around a lot.

People that reach out with enthusiasm from North Dakota don't know that I was only there for about two months, and then we left again! [Laughs.] So I have no ties, no memories of North Dakota – but I was born in the cold.

Coat: Rag & Bone

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: That's a little like me – I was born in a city called Coventry, England and I left when I was four. Forever afterwards, they want to claim me, they want me to be an ambassador for the city – I remember nothing of it!

As an executive producer, I was somewhat involved for the casting of Jack Reacher. You've done a sensational job – and I did not know about your military background! Now I realise…

Alan Ritchson: Yeah, I cheated! There's a formality to the body language and the movements and the posture of military individuals. I still remember watching my dad when he'd bring us to work in the hangers. He'd shake people's hands and his posture was always so held tight. He was more relaxed at home.

That stayed with me, the way that we present ourselves. Commit to a handshake, look people in the eye. There's a chivalry and formality to the military that I think a lot of us miss in society today.

Lee Child: I agree with that. My dad was a veteran, like everybody of his generation. The glimpse into that world is fascinating to me.

That's where the Reacher series came from: the extreme disparity between the military civilisation and civilian civilisation. They're like two different planets – and if you're used to one, you find the other one very strange.

Alan Ritchson: It's the one percent that protects the 99 percent, you know what I mean? This is a population that's so exclusive and yet does so much work for the betterment of society as a whole.

It kind of becomes a mystery to people, this otherworldly thing that we don't interact with as civilians. And when they return from deployment, the strange land that they occupy outside of the forces that they're in – that disparity is interesting, yeah.

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: It really is. We should talk more about the mental health thing. That is now the final frontier. For instance, my grandfather was also a veteran and was horrendously wounded in World War One. He got injured in 1915 and it did not heal for 20 years, until 1935.

Back then there were no antibiotics, nothing like that. He had this wound for 20 years and they just ignored him completely.

Whereas now, our physical battlefield medicine is sensational but we lag behind the mental side and we've gotta catch up. We've got to put the mental on the same status as the physical.

Alan Ritchson: Absolutely. People who are physically injured are treated differently than those with some kind of mental disorder.

I work with a couple of organisations in the mental health space and I've had my own experiences that have taught me a lot – about how real those peaks and valleys can be. How troubling that can be for somebody trying to adjust to a 'normal, healthy life'. But destigmatising that conversation is where we have to begin.

More of us talking about our own personal experiences in battles. There are bridges of empathy. Normalise the language around mental health.

Lee Child: I agree. I've really had no serious problems in my life but I was very experienced by the Olympics recently, with Simone Biles. Who basically is a goddess of athletic performance. She came out and said, "it's OK not to be OK". I found that very poignant. I wish that when I was 14 or 15, somebody had said that to me. Not that I had problems, really, but just that feeling that you've gotta bottle it up, you've gotta hide it, you can't talk about it. We need to get rid of that.

Alan Ritchson: That was interesting because there's a percentage of people who maybe wouldn't otherwise have rallied behind that kind of comment.

We can see a groundswell of people understanding and empathising with others in that respect. But that was still rather polarising, which can be a little disheartening.

A lot of people saying, 'she should've sucked it up' – there's still a lot of people on both sides of that conversation, unfortunately.

Coat: Rag & Bone; turtleneck jumper: Paul Smith; jeans: John Varvatos

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: You've grown up with these two airforce officers in a very non-BS world. And you turned into a creative person – an actor, writer, producer, director and so on. How did that happen? And how did it go down in that world you were brought up in?

Alan Ritchson: Credit where credit's due – my parents fostered a curiosity. I think specificity and curiosity are two of the most important attributes to defining an interesting human being. They helped develop those qualities early on. They supported the strangest endeavours.

I grew up in the South with mullets and four-wheelers. I took an interest in singing and dance – I wanted to try a dance class. I could've been born into a family with a dad who felt insecure about that. He didn't blink. I'm a product of my environment and I was lucky in that respect.

The only time my father ever said no – I knew there was no fighting him on this – was when I told him I was going to sign up for special forces. I thought following in his footsteps to some degree would be something he'd take pride in – and it was quite the opposite. I think he saw something in me – there was that creative spark that he recognised and he wanted me to use that.

The only time my father ever said 'no' was when I told him I was going to sign up for special forces

I'm a bit of a wanderer. I get restless and bored, I try things. I was a vocalist in high school. We come from a fine arts area, naturally near military bases there's a cornucopia of high creatives. They spring up in that area for some reason. We had a very competitive fine arts programme, we would travel around the country, performing. I was one of the first sophomores in high school to make it into this group called Opus, the most exclusive singing group. For my senior year, I wanted to try an acting team – my choral instructor couldn't understand why but I'd done singing! I was a little bored. That's always been my approach to life. Just explore.

Acting found me through modelling – which is rather a fruitless industry. But it was something I hadn't done and it was my ticket out of the town that I was in. When I was 18, I was living in a truck outside a grocery store because I was so fiercely independent, I didn't want anyone having control over me. Going to Miami to model was a ticket out of town and I took it.

Lee Child: This is getting even more uncanny about Reacher. In one of the books, he propounds a theory that nine out of ten people are happy to stay around the campfire but the tenth person has gotta go, gotta wander, gotta explore. So you're that guy, who struck out on his own path.

For me, the key component of success is that you're loving it and you know you've arrived at your destination. When did you first figure that out?

Alan Ritchson: For me, it was several years into my career. I moved to LA as a model; I knew there were opportunities in music, TV and film that I could maybe try. In three weeks I was on a show, Smallville, playing a superhero [Aquaman]. It opened all the doors. But because it was so easy, I didn't really have time to learn the craft. I was coasting on instinct. That fed me really well for a long time.

It's easy to get lost in the commercial side – I'm making a really good living doing this, clearly I've got it figured out.

Four, five years in, I auditioned for a film that was huge. Everybody knows what it is. I'd just come off a show, I was feeling a little arrogant, jaded about the industry. If I look like the guy, it doesn't matter how I act. I walked in with that attitude, and I got a call from the casting directors – that never happens, even if it's positive! Let alone a negative note. But I got a call from the casting director, saying, 'when you walked in, we put our clipboard and pen down, thinking we'd finally found our guy. If he's got the craft, this is his. It was your part to lose.'

It was a punch in the gut that sent me on a very different path. I'm so grateful for that loss. That was the moment I decided who I was going to be in the industry.

I got in a couple of very private classes with masterful people and worked in a theatrical setting, studying theatre with some amazing talents. I decided to really embrace the craft and understand what that meant. I was humbled, and I was also full of a confidence and optimism that brought a lot of joy to the work that I hadn't had before. That was the turning point for me. It was well into my career.

Coat, turtle-neck jumper, trousers and boots: Givenchy

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: Hollywood works incredibly hard – the workload is intense. People will work 20 hours, sometimes more. I think that's something that's hidden from the observer – if people understood how much effort goes into the work, I think they'd have more respect for it.

Alan Ritchson: Yeah. It's a little bit like Whac-a-mole, if the moles popped up in the most glamorous way! We see the side of the industry that's really manicured. What goes on when the mole's down under can be quite gruesome at times. A lot of people have a very difficult time making ends meet between jobs. Pay cheques can be years away.

We're finding ourselves as a society in where our work-life balance lives. People who work in film and TV are often really lovely, family orientated people – young, kids at home, and they don't get to see them very often when they're on a five, six month stretch doing a show. Where do we draw a line between the perfectionism that the industry demands and how much time we spend with family?

Lee Child: When we hung out on set, I found out you're pretty good at playing chess...

Alan Ritchson: I love chess! It's really my love of jellybeans that got me into chess. In third grade, there was a chess club at school and there was a bowl of jellybeans at the front of the classroom. You'd play after school, and if you won you got one jellybean. I loved eating those jellybeans! I was viciously competitive. My older brother got me into that – we would compete against each other. I didn't see a difference in age, just an opportunity to win.

I was living in LA and my brother was in San Diego. He's an engineer and he was at a plant nearby. He came by, we wanted to play a game so we set up a board. He hadn't beaten me in years – and he absolutely crushed me! He'd been studying all the books! He knew he was gonna open one up on me. Once again, I chased him down – I had a target. That was the season that took me to the next level.

Shirt, waistcoat and trousers: Suit Supply: watch: Breitling

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: It fits really well with Reacher – he's always one move ahead of everybody else…

Alan Ritchson: I love that about Reacher. He's calculating. This possibility feeds into this possibility. Also, he's not always right – there are times he makes a wrong assumption. I love the fallibility – if I'm playing a chess game with somebody, I'm not gonna win 'em all.

Lee Child: And Reacher can win a battle but not the war. A lot of the stories involve horrible things. He can solve the localised problem, help an individual or two, but he can't eradicate evil from the world. He lives with a permanent compromise – what does winning mean? You can win to a certain extent but not 100 percent.

Which is also torturous, isn't it? The idea that there really seems to be no end to injustice, no matter how hard we try, can be rather defeating. Where does that live in him in your mind? To me, that's sort of a simmering kettle with a lid on it...

Lee Child: It's a function of maturity and experience. When I was younger, I thought the world was perfectible. That we were on a course that was going to end up in a better place, and problems could be solved, and so on. Then as you get more experienced, you realised, 'I can get through the day, maybe help a couple of people, but I'm never gonna really solve the problems'. And that's where Reacher is. He's beginning to realise that. And he's not defeated by it, but he's kinda sad about it.

Alan Ritchson: Is it hard for you, having dreamed up these characters? You had to have some fixed image of them in your head. Is it difficult for you to switch that image in your mind?

Lee Child: Yeah, absolutely. That's really the central issue from the writer's point of view. A book is completely made up – it doesn't exist anywhere. It's just a story that hangs in people's imaginations with no physical reality at all.

With TV and movies immediately you are into the world of physical reality. These are real people in real space. For instance, Willa Fitzgerald, who plays Roscoe, was nothing like how I had mentally pictured. I'm incredibly visual about it – I'm living with this character for six months while I'm writing the book and I see her incredibly clearly in terms of appearance. Willa was not like I had envisaged – but she just owns her scenes. I'm like, I was wrong! This is what Roscoe is like!

Obviously a writer includes a lot of autobiography – Reacher is me in my dreams. Of course he is!

So I'm putting myself into Reacher – then you come along as an actor, playing Reacher. So a substantial part of the time, I see you on screen, playing me! And it is the freakiest possible thing!

Occasionally there'll be a reaction, a look that I do. That part is the most powerful for me – seeing little tiny echoes of myself that have survived a two-way translation process over a quarter of a century.

Alan Ritchson: Well, I appreciate you entrusting me with you! You have such unique mannerisms it was fun to shape some of that into Reacher.

I'm captivated when I watch it; it all happened so fast I don't recall everything we shot, so now I'm watching this as an objective observer, and I can't take me eyes off what the other actors have been doing.

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: I agree – we've been lucky. Reacher carries the weight, but it depends on the ensemble. Reacher is worried about being lonely – he has a suspicion about other people, but a desire that they will be OK, so he can connect at least for a couple of days.

If you're Reacher's friend, you're the luckiest person in town; if you're his enemy, then not so much.

Alan Ritchson: For people who don't know, the showrunner in TV is the top of the creative pyramid. They have a hand in every piece of the pie – from casting to crew to set design. The scope of the show is in their hands. As the writer, is it hard for you to pass the baton to a showrunner – in this case, Nick Santora.

Lee Child: Not really. It's all about picking the right person. Nick is exactly what you want – a peculiar blend of 100% artist, writer and creator, but also 100% down-and-dirty operative. He has a job he has to get done.

It's no good believing that stuff 50:50, you have to believe both parts 100%, which is arithmetically impossible, but you have to force yourself into that situation. If you believe in the person, it's easy to give it away.

Plus, it's already happened. Your first book prior to publication, only you know about it; as five, ten books come out, the character becomes effectively owned by everybody; the ownership migrates outward to the reader.

Alan Ritchson: I can't imagine after 25 years of conversations about Reacher, that you still have such an earnest, invigorated approach to this world…

Lee Child: I started in what you could loosely call show business when I was 17. I've learned that if you have an audience, you're the luckiest person. It is such a privilege.

I hate people who provide the first part of their life desperately trying to become famous, and then the second half moaning about it. That makes no sense to me. If you're gonna do it, do it right.

I'm always available, because I'm so thrilled and flattered that anybody is reading my books.

Alan Ritchson: Were there any ideas you could never get around to?

Brian Higbee

Lee Child: There were hundreds. Of course, Reacher has been artistic and creative, but it's also a job. It's kind of weird to offer something different to what people expect from you.

If I go to Yankee stadium, I know I'm going to see baseball. Entertainers have that responsibility. It's about giving people what they want. If people demonstrate a desire for something that I am capable of giving them, why wouldn't I?

Alan Ritchson: Do you have a favourite book in the series?

Lee Child: There were books where I had a problem; something I had to fix, or find my way through. If I've done that well, then I get a lot of satisfaction from that. But the reader doesn't know; and I'd prefer them not to know.

Graham Greene once said "Success for a writer is merely failure delayed" – and you do feel like that. You do a book and it's like 'Great, I got away with another one. They haven't found me out yet.' That is about the best feeling I can have.

Alan Ritchson: Every time I get to see a glimpse inside your head it's invigorating.

Lee Child: Likewise. This is so collaborative now. There are around 300-400 people working on the show in some capacity – and it's very inspiring. All these people focusing on one thing to deliver it.

Writing is entirely solitary – you're entirely on your own for months at a time. And then to move into the TV adaptation with hundreds of people who know everything about the story – who know more than I do, in fact – is amazing.

I never reread a book, as I'm always focused on the next one.

Killing Floor, which the first season is based on, I had never reread ever – not in 25 years. But I did recently and it was much better than I thought it would be.

I was anticipating a rather clunky, first-novel feel to it. I was thrilled for a day or two. Wow! This was actually pretty good. Then I was depressed – I thought I've gotten no better since my first book.

Alan Ritchson: I wouldn't agree with that. My experience as a reader is that every book bested the one before. Somehow you continued to outdo yourself. You wrote the very first manuscript in pencil, right?

Lee Child: I was very aware that this was not a hobby – it was a job. I would have to self fund. When I started the first book, I didn't have a computer, so I wrote the book in pencil.

It's a good way to do it. A very famous Italian cultural critic called Umberto Eco was outraged when the Italian school system stopped teaching fine handwriting. He thought this was a terrible mistake, because if you write by hand, you cast the whole sentence first before you put it down on paper. There's some truth to that; if you are writing by hand, you write better. You want to get it right first time.

I launched in in the middle of the story: "I was arrested in Eno's diner." I'll always remember that first line. It just popped into my head – and then it was off to the races. It never stopped after that.

Alan Ritchson: That's amazing! Thanks, Lee.

Watch Reacher now on Prime Video.