Photographer Dennis Morris was born in Jamaica in 1960, so as a music-mad teenager, he wasn’t going to pass up the opportunity to meet the rising reggae star Bob Marley.

Morris’s family had moved to London when he was six, but a growing love of photography and music would collide in spectacular fashion when, as a young teenager, he bunked off school to accept Marley’s personal invitation to document Bob Marley and the Wailers on their first-ever UK tour.

A Dennis Morris photo had already graced the front page of the Daily Mirror newspaper when he was just 11. He had inadvertently stumbled across a feisty demo by the PLO on the streets of London and, showing wisdom way beyond his years, sold his pictures to a photo agency on Fleet Street for £16. A hugely successful creative career was underway.

Since then, Morris has photographed many of the world’s top music stars, been the art director of Island Records, and even had a stint as lead singer of the reggae/punk fusion band Basement 5.

His latest venture is the retrospective exhibition and book Music + Life, which combines his iconic music images with his reportage of life in the black, Asian, and white communities of London.

The exhibition is running at The Photographers’ Gallery in London until 21 September, with the accompanying book featuring more than 300 of his pictures.

To discover more, we spoke to Morris about his career, mojo and motivations…

Square Mile: What drove your initial interest in photography?

Dennis Morris: I was in a choir in the East End [of London]. The patron of the church was a man called Donald Paterson, of Paterson [darkroom] Products. He created a photographic club for the choir boys. I guess he saw my enthusiasm and potential.

He took me under his wings and taught me everything. He took me to galleries, museums… you name it. It really all stemmed from him. At the age of nine, I first saw the magic of photography. I saw one of the older boys printing in the darkroom. From that moment on, I knew that this was going to be my life.

SM: What was your first camera?

DM: I started with a Kodak Brownie. Believe it or not, probably one of my most famous pictures was taken on a Kodak Brownie. It was the first competition I won. I went on my first school journey and there’s an image, which is in the exhibition, of my two schoolmasters with their trousers rolled up on the beach in Ilfracombe [Devon]. I won the prize for the best photograph from the holiday. That really encouraged me.

Bob Marley, Live at the Lyceum, London, July 1975: This image was used on the cover of Live! – the live album release of Bob Marley and the Wailer’s second performance that night. “That’s one of my favorite live shots of him, because of the way his locks are flying,” says Morris. “It’s like a helicopter blade. I love the beauty of that shot.”

Spliff, 1973: One of the most famous pictures of Bob Marley ever shot. “One day, he said to me, ‘Dennis, let me show you how to smoke a spliff.’ I shot one, two, three frames. By the fourth frame, I was gone. I was completely high.”

SM: Were you aware of other photographers’ work from a young age?

DM: From the magazines and the books that Mr Paterson gave me to look at, I became very aware of people like Don McCullin, Bailey, [Robert] Capa and [Henri] Cartier-Bresson. The biggest discovery for me was Gordon Parks, who was the first black photographer to work at TIME magazine and went on to direct Shaft and other movies. That was a big breakthrough for me to see that there was another black person out there [in the business].

SM: I believe your careers teacher discouraged you from becoming a professional photographer?

DM: Yeah. When I was leaving, he asked me what I wanted to do, and I said “I want to be a photographer.” And he said, “Don’t be silly, Morris. There’s no such thing as a black photographer.” And I said, “Well, there’s Gordon Parks, James Van Der Zee to name a few”, and he was like “Who?” Different days!

SM: Can you tell us about meeting Bob Marley for the first time?

DM: When I was at school, I was very much into music. Music papers were around, and I’d read that Bob Marley was coming over to do his first UK tour. I decided not to go to school on the day of the first [tour] date, and went to the Speak Easy Club in the West End. I got there about 10 o’clock in the morning, but I didn’t know that bands don’t do soundchecks at 10 o’clock in the morning. Around 3 or 4 o’clock he [Bob Marley] turned up. I walked up to him and said, “Can I take your picture?” And he said, “Yeah, man – come in.” It all started from there.

During his soundcheck, when he had a break, he was asking me what it was like to be a young black kid in Britain, and I was asking about Jamaica because I had little memory of it. He took to me for whatever reason, told me about the tour, and asked me if I’d like to come along. The next morning I packed a bag as if I was going to do sports, and went to the hotel [where they were staying]. There’s a very famous picture of him in the van turning back saying to me, “You ready, Dennis?” I said, “Yeah”… click… and there is one of my most iconic images.

Babylon By Van, London, May 1973: This is one of the first photographs Morris took of Bob Marley, shot in their Ford Transit tour van. “He just turned around and said, ‘You ready, Dennis?’ I said, ‘Yeah’… click… and there is one of my most iconic images. That’s how the adventure began.”

SM: What camera were you shooting on at the time?

DM: I had a Leica M3 that Mr Paterson had loaned to me. All those tour images were taken on a Leica M3… a beautiful camera. It was a terrible camera to use in live situations, with the focusing on the rangefinder very difficult. But I had mastered it – and I did all my great work and my favourite shots on an M3.

SM: How long was the Bob Marley and the Wailers UK tour?

DM: It was supposed to last for a couple of weeks, but within a few days, it collapsed. What happened was one morning they woke up and wanted to play football. They opened the curtains and it was snowing – they’d never seen snow before. Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer said, in Jamaican patois, “Wa dat?” I said, “It’s snow”. [They replied] “Wha ya mean, snow?”

They said that it was a sign from Jah that they should leave Babylon. Bob was quite open and saw touring as a way of delivering the message, but Peter and Bunny just hated the idea of touring; they hated the food, they hated Babylon and couldn’t wait to leave. So, the tour collapsed and they went back to Jamaica.They came back a couple of years later and played The Lyceum. Bob remembered me and gave me a photo pass [to the gig], and I ended up getting the cover of NME, Melody Maker etcetera.

But my ambition was never to be a rock photographer; my ambition was to be a war photographer. Reportage was my big influence and I basically just took that technique within rock. Instead of doing your normal rock-type photography – band against a wall, that kind of thing – I did studies in that way, which was very unique at the time – and still is, I think.

Admiral Ken with Bix Men and sound system, Hackney, London, 1973

SM: But you were also documenting life in London at that time?

DM: Yeah. All the time. I was really honing my craft by taking images of my surroundings. I was taking shots of my neighbourhood in Hackney – living conditions, the whole shebang. Then I discovered another area [of London], Southall, where I did the same thing. I went to that area and photographed all of the cultural side of their lives – weddings, temples, housing – you name it, I shot it.

SM: How did the connection with the Sex Pistols and John Lydon come about?

DM: We kind of grew up in the same sort of neighbourhood. He was in Finsbury Park and I was in Hackney, but he went to Hackney Technical College for a while. Like me, he was also very much into reggae, so he used to go to the blues parties, dances etcetera – that kind of thing – and we sort of knew each other.

When the Sex Pistols signed to Virgin [Records] my name was put forward and he saw those pictures I did of Bob [Marley]… one thing led to another and I ended up photographing them. The first day we met outside of Virgin’s office in Portobello Road and we just built up a friendship. From then on, it just escalated to me being with them [the Sex Pistols] 24/7.

Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten, S.P.O.T.S tour, Coventry bus station, UK, 1977: “With Sid [Vicious] everything he ever did was going to lead to something. You had to just be aware of that, and get it. The night after the Sex Pistols gig in Coventry, my room was next door to Sid’s. All through the night I just kept hearing this almighty racket. It was just like hell was going on there. When it stopped, I got up, pushed the door, it wasn’t locked. He had completely destroyed his room. It was like a war zone where there had been a direct hit. Anything that could be smashed was smashed – he had set his bed alight, the whole thing. I just got these amazing pictures. And there he was lying in the middle of it, passed out.”

SM: Can you give us some insight into your creative process?

DM: My creative process is exactly the same as it was from the very beginning. I’m a people’s person. Even if I’m working in a studio, my approach is in a very reportage way. I tried working with assistants, but it doesn’t really work for me, so it’s normally just myself. I’m always trying to look for that sort of inner self, not the self that was projected… taking away the mask. So, that is my process.

You’re not making a movie, where you shoot, shoot, shoot. In photography you’re looking for that one shot and when you have that shot, you know it – and that’s what I’m always looking for. That one shot. That’s how I work creatively.

SM: Your new exhibition and book, Music + Life, is a mixture of your work…

DM: It’s not just music. It covers everything really… all the reportage and social documentation work I did. There are three bodies of work in there – ‘Growing Up Black’, ‘Southall: Home From Home’, and ‘This Happy Breed’, which is a title from a Noel Coward play, which became a film. It’s looking at the white English community in the East End.

SM: How did Music + Life start?

DM: It came about from Simon Baker [director of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris], who had wanted originally to do it at the Tate Modern – they declined and he moved on. Two years ago, I did a show at Kyotographie, a photo festival in Japan. Simon was there, and we sat down and spoke about it. Over two years, we eventually got it together and opened in February 2025 in Paris. It was the most successful show they’ve had in their 50-year history. People were coming in their droves.

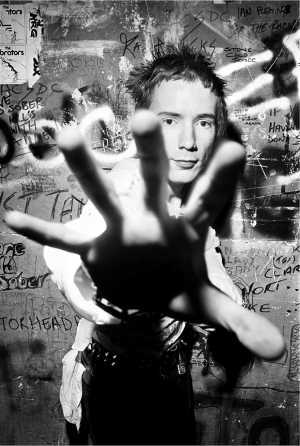

Johnny Rotten backstage at the Marquee Club, 23 July 1977: “In photography you’re looking for that one shot and when you have that shot, you know it – and that’s what I’m always looking for."

SM: How did you choose the images to include in it?

DM: It was a very hard process. In the exhibition there’s nearly 400 images, and in the book there are about 300 or so images. To really cut it all down was quite hard because I still feel there are some images that should, and could, have been in there but there was a [finite] space [to fill]. But I’m happy with it.

It gives a glimpse of what’s there and what I’ve done. It stops around the 1990s – and I’ve done so much more since. So, it’s a retrospective up to the 1990s, but not beyond.

SM: Did you get feedback from the people who saw your work on show at the MEP in Paris?

DM: I was there on a regular basis and I’ve had people crying when they’re very emotional looking at the images – from the [Sex] Pistols stuff to the [Bob] Marley stuff to the social documentation. People were very, very emotional. It’s kind of like an eye-opener for a lot of people as they never knew or understood about the West Indian community or the black community in England and the history of it all. They never really knew about the Sikh community or even The Happy Breed side of things.

SM: I guess it’s because your photography is inherently truthful?

DM: That’s a very good way of describing it. That’s what I aim for. I aim for the truth. I look for the real person. I take away that mask and show the real person. That mask could be a beautiful mask, in terms of what they portray. But when you take that away you realise that, hey, they are even more beautiful in that sense.

A man with his two daughters – and his most prized possession, Southall, 1976.

SM: Do you have a favourite image from your career?

DM: The thing about my work is that I’ve got over 100,000 images and I literally know every single picture I’ve taken; every single one of them has a particular meaning for me. They’re like my children in that regard. It’s very difficult to have a favourite, but you love each one for the way they are.

So, it’s the same thing – like that shot of Bob [Marley] in the van brings back memories for me, the shots of Marianne [Faithfull] brings back memories, the shots of Public Image, John [Lydon], the Pistols… they’re all very personal.

SM: Have you embraced digital photography?

DM: Yeah. But even if I’m shooting digital, I shoot as if I’m shooting film. It goes back to the days before digital when you had to know what you were doing, what you were going for, and you only knew that you’d “got it” when you developed the film and looked at it.

It’s really the same process when I shoot digital. I don’t stop and look [at the screen on the back of my camera] because, by doing that, you break the momentum and that flow. I just keep going. The other thing about the digital side of things is that, with scanning all of my negatives, I’ve learnt that I’m getting more from my negs now than I was before. That advancement is wonderful.

SM: What are you most proud of from your career?

DM: To be able to achieve what I’ve done. When I look back to what my school careers master said to me, I think I’ve gone through that glass ceiling. For me, that’s the greatest achievement – to break down all those barriers. It’s great to see a lot of the young photographers coming up – black or white. I constantly get messages on Instagram and emails saying things like, “Because of you I went into photography; you influenced my work” etcetera. It’s nice; it’s a great feeling.

The truth is I never went into photography to make money. I found something that made me feel alive. That’s why I went into it – pure love. If you go into it for love, and you perfect your craft, the money side will come.

View on Instagram

To find out more about the exhibition and book Dennis Morris: Music + Life visit thephotographersgallery.org.uk and thamesandhudson.com. To see more of Dennis Morris’s work go to dennismorris.com