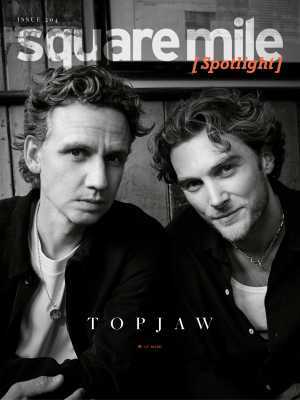

“I like birds and I like cars,” declares Jesse Burgess – one half of Topjaw alongside Will Warr – as we wait for a spice bag at Mc & Sons in Vauxhall. Oh God, I think. A chiselled heartthrob declaring an enthusiasm for hot women and Lamborghinis? It’s like interviewing Gordon Ramsay, and him admitting he’s partial to lobster.

But my initial assumption is wrong. Burgess is, in fact, a bona fide birdwatcher: a Merlin Bird ID app obsessive and a martial eagle enthusiast. It’s what fills the rare gaps between having one hand on a microphone and another on the pulse of where chefs, critics, celebrities, and even a Prime Minister want to eat – while Warr sits behind the camera quietly stitching it all into cultural currency.

There isn’t much time for watching warblers, mind you. Topjaw, the boys tell me, occupies pretty much every waking moment. “It’s all-consuming,” Burgess remarks. “You can get really emotionally affected by a film’s performance,” says Warr. “Jesse is passionate about the analytics and diving in and overanalysing – I mean, analysing – the performance to do better. You take all of that home with you, of course. I have to be pretty tough, leaving work and trying my best to disconnect from that social media world.”

That forensic streak – Burgess’s fixation on the numbers, Warr’s insistence on a higher-gloss production beyond iPhone-grade cheese pulls – has helped propel Topjaw as one of the biggest names in food media. Topjaw, for the blissfully offline, is the duo’s video juggernaut: longer-form travel guides and short-form street interviews with chefs, critics, and celebrities that can transform a restaurant’s fortunes overnight.

Their 30-second “Best of London” video with food critic Grace Dent hit 2.4 million views on Instagram; their combined YouTube, Instagram and TikTok following tops 1.5 million. In an era of dwindling attention spans and our insatiable hunger (read: addiction) for short, snackable content, it comes as no surprise that a Topjaw clip can now pack a dining room faster than any newspaper review.

Although their rise feels as sudden as the latest Soho hotspot, Topjaw was no overnight success. It began a decade ago when Warr (freelance filmmaker) and Burgess (marketing) worked alongside each other at Jamie Laing’s sweet company, Candy Kittens. They bonded quickly, made a video series travelling to university towns in a proto-Topjaw style, then shared a studio. Topjaw itself began as a side hustle, producing long-form travel shorts that took days to shoot and weeks to edit, and remained a side project for seven and a half years. “We were very lucky that we always had some sort of income and we could have a bit of fun with Topjaw,” Warr recalls.

Timing helped. Since the early noughties, casual dining had been “becoming both experiential and a lot more brand driven,” Burgess says. London was in the grip of the burger boom: Byron Burger felt revolutionary, Burger & Lobster had us queuing for plastic bibs, and elsewhere, Gail Mejia was churning out sourdough sandwiches at The Bread Factory, a wholesale business which later partnered to open the first Gail’s.

It was an age of gourmetfication, of mac’n’cheese, truffle oil and balsamic glazing. Instagram arrived, as did food porn and hashtags. Food stopped being just what we put on a plate and became part of who we were. And, increasingly, it was as much about how it looked as how it tasted because we had phones with cameras. Walk through London today, and the walls whisper of tiny martinis, jambon beurre, how well a Guinness is poured, and whose £1 oyster hour is winning. The Food Programme broadcaster Derek Cooper wrote in the 1960s that “food is not something you talk about” – we couldn’t be further from that right now in the UK.

The pivotal moment of Topjaw’s ascent came when they realised the world preferred its food 30 seconds at a time. “We began to watch so much short-form content, we couldn’t possibly put out 15-minute videos on YouTube each day,” Burgess says. The content shrank. Swift street interviews posted on Instagram, interviewing chefs and celebrities from Monica Galetti to Idris Elba to Jamie Oliver to Charli XCX.

Best pub? Best curry? Best coffee? Most outrageous value? Tight editing, meme inserts and Burgess’s deadpan commentary make the whole thing oddly addictive and endlessly snackable. One clip leads to another, and suddenly you’re under the covers in a dark room, scrolling, unable to stop. During their peak output, they were posting daily.

That algorithmic reach can, in some cases, change a restaurant’s life overnight. Dominic Hamdy of Bistro Freddie, Kaneda Pen at Mamapen and Trinity’s Adam Byatt have all spoken separately about Topjaw giving their bookings a sharp nudge. Not everyone is delighted, though – some gripe when their once-sleepy favourite suddenly has a three-week waiting list (death threats have been made towards the duo for ‘ruining’ Italo in Vauxhall).

How do they feel about accusations of “wrecking” restaurants? Burgess sighs. “People say that, but it’s rarely true. Hospitality’s never been tougher – power bills are insane. If you love a quiet local spot because you can always get a table, odds are it’s quietly dying. Even busy restaurants aren’t making big money. If we fill the room, that place probably survives. And honestly, we get more credit than we deserve. Maybe we start a snowball, but ultimately, the ingredients were already there for it to be a great place anyway. We just nudged it.”

Creative pairs can often mimic siblings – alternating tenderness and exasperation. Burgess and Warr are no exception. “We’re like brothers,” Burgess says. They argue, make up, move on. That trust, they admit, is crucial to Topjaw’s growth: it lets them be choosy about guests, ideas and cuts. At around 220 episodes, they’ve learned the power of selectivity: pruning what doesn’t hit and declining guests, a rebuke to the quantity-over-quality gospel propping up many creator careers.

Topjaw’s timing is interesting. It comes at a weird moment in food media, where everyone can be a critic and everyone is monetisable. Burgess’s gripe is familiar to anyone who watches the space closely: too many creators are paid to praise the places they visit, and too much of that praise reads like advertising dressed as appetite.

“I think there isn’t enough authenticity on social media,” he says. “Two pieces of content by an influencer will be them genuinely going and liking something. The third is them getting paid £1,500 by some market stall – and they don’t disclose that.” He’s adamant: “We have not and will not ever take any money from a restaurant hospitality business to say their food is good. People still seem to think that we get paid to go places, but we do not.”

They monetise elsewhere – brand gigs with Google Lens, Bumble and the like – and their refusal to take restaurant cash isn’t to be knocked in a landscape where even legacy media is often indistinguishable from PR. That stance earns them praise but not immunity. Some argue a superlative “best of” format flattens complexity. Burgess himself admits that asking chefs for what’s overrated “grounds the rest of your recommendations”. It does – but spectacle scales better than nuance, and a 30-second “most overrated” will always travel further than 800 words about provenance or technique.

They’re not alone in chasing reach. When broadsheet restaurant critics are reviewing Angus Steakhouse for sport, and Brooklyn Beckham (who only recently cremated guanciale on camera while making a carbonara) is filing Financial Times food op-eds, everyone’s dabbling in shock or rage-bait. As for their competitors? Food influencer Eating with Tod, when not covered in beef dripping, barbecue sauce or drool, recently referred to a plate of octopus as lobster and a leg of jamón ibérico as “jambon” at Lurra, so at least the duo can get their facts right.

That’s not to say the two haven’t been burnt by the perils of risk-taking, which crystallised in an interview with former prime minister Rishi Sunak. When Number Ten wrote to the duo requesting a prime-ministerial interview, the boys took it as a compliment. They filmed, edited, sent, and were surprised when Sunak’s team approved what they had expected would be declined. The film went out, and the backlash was immediate: viewers read the interview as an endorsement for his politics, not curiosity over his palate. “If you’d watched the whole film, you would’ve laughed,” Burgess says. The lesson was swift and absolute: “No more politics.”

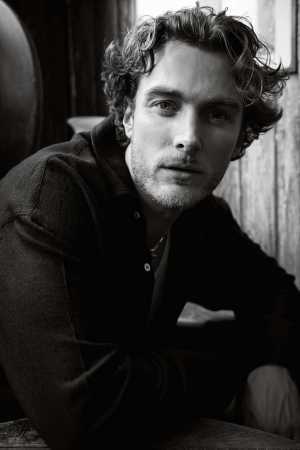

Chefs remain their compass. “If you’re a top chef, you’re probably not going to tell people to hit up Strada,” laughs Burgess. “Liam Gallagher isn’t going to have bad music taste, is he?” Burgess will also soon star independently of Topjaw in a Gordon Ramsay-produced show called Knife Edge: Chasing Michelin Stars. It airs on Apple TV, examining what it takes for chefs to earn a Michelin star. He rejects the idea that Michelin is perhaps arbitrary, archaic or reductive: “For any organisation to be around 125 years and be more relevant now than ever is crazy. It’s so potent.”

Other rankings like the World’s 50 Best or the National Restaurant Awards? “Just tribute acts trying to make money with huge events and sponsors,” he remarks. A leap from social media to TV? Burgess doesn’t think so. “The Netflix and the Apples and everything; that’s still online TV. It’s basically YouTube. We had a meeting with YouTube recently – and they said that in fact 60% of people who watch Topjaw watch it on their TV.”

Despite being fully immersed in the food industry now, neither grew up in especially culinary homes. “Mum makes a mean fishcake,” says Warr. Burgess’s mother was a private-jet air hostess, and he remembers her bringing back far-flung foods – stollen cake from Cologne, bouncy prawns from the Med on plastic platters, beluga caviar left over from Jay-Z or Pharrell’s flights. “I was very much a curious eater; I wasn’t fussy at all. I’d stick anything in my mouth.”

Orbiting food so consistently takes its toll, however. “I feel so lucky. We both feel so lucky to do it every day. Jesse has a little bit more strength and willpower. He’s very good at keeping fit and getting up to run. But I’m trying harder at the moment when we’re not doing our Topjaw filming to look after myself a bit better,” says Warr. “We do like a good time, though,” Burgess adds. “Get gout or die trying,” Warr deadpans.

For all the crisp edits, sharper jawlines and bouncing ringlets, they’re still human. Burgess recently married singer Taura Lamb; Robin Gill from Darby’s and Black Bear Burger catered the event, and the wedding cake was topped with two troll dolls in bridal regalia. Vogue even offered the exclusive, which Burgess found bemusing. Warr, a father of two, is rarely not behind the lens. This weekend, he’s taking a “very exciting car” he borrowed up to the Cotswolds and plans to rig it with cameras.

What’s next? Burgess previously mentioned in an interview that Anthony Bourdain left a big hole in terms of actually good food and travel content. Do they see themselves as filling that void? “I will spend every day of the rest of my career trying [to fill that space of Bourdain],” Burgess says. “I feel like he was a walking, talking encyclopaedia.

“I will never, ever have the chef experience, the prowess and the scars that he had. But he’s the best thing that ever happened to food media. No one else is coming close. I’m immature in comparison, but then, he did love dick jokes.”

View on Instagram

Follow the boys at topjaw.co.uk. Knife Edge: Chasing Michelin Stars is out now on Apple TV