Finbarr Notte had to be brought low before he could start his climb to street art stardom. Already in his mid-40s, at the turbulent end of a long-term relationship gone bad, denied access to his children, and in a job on the technical side of a digital advertising agency – from which he was eventually fired – it was then that he decided he had nothing to lose.

“There was a lot of soul-searching at that time, and painting cleared my head and took me out of the angry resentment I felt,” he recalls. “At work, I was surrounded by creative people and it struck me that none of them were especially any more talented than me, nor any more confident, despite their [art] educations. I think until that point I had allowed a lot of doubt to stop me being creative.

“But the fact is that nobody cares about your self-doubt. When you’re starting out, nobody really cares what you’re doing,” he adds – you’re free to fail, to experiment. “You’re in charge of your own encouragement. Of course, it’s still very easy as an artist to question what I’m doing. Even in the space between starting a painting and finishing it there’s a lot of ‘Shit, this isn’t going to work’.”

That maybe matters more for Notte than for many, as the Cork-born artist’s works tend to be the size of a building. They pop up on walls from Columbia to Canada, New Zealand to Hong Kong – and stand out from most urban art in very much not being high-concept images produced using stencils in the dead of night.

Notte goes by his more ‘street’ tag of Fin DAC – the DAC stands for Dragon Armoury Creative, the name of his online portfolio before he went pro. He is today best appreciated for his dramatic, alluring, richly detailed and highly colourful portraits of Asian women in their traditional, ceremonial dress, inspired in part by his lifelong love of manga and anime. He has worked with the same few models – his “muses”, one Chinese, one Japanese, one Korean – for years.

HOMAGE TO Kitagawa Utamaro

“When it comes to my personal favourites from the collection, it’s a toss-up between Jean Michel Basquiat, Julian Opie and Kitagawa Utamaro– they are really hard to choose between as they’re favourites for very different reasons.”

He has always taken inspiration from the Victorian period’s Aesthetic Movement and its insistence on producing art that was beautiful more than meaningful, providing an escape from the perceived ugliness of the industrial age. He calls what he does “urban aesthetics”, all about an effort to beautify often rather decrepit inner-city locations. Unlike so much street art, you won’t see his works making arch comments about politics.

Yet Notte knows that talking about beauty is all rather out of fashion. As he notes, in modern art interest in the female form is rather frowned upon these days: “I don’t think my work will appear in high-end galleries because that’s not the kind of thing they’d promote,” he says. “Beauty doesn’t have to be perfect. I think a gnarly wall can be beautiful. But beauty, as a subject for paintings, is of limited kudos in today’s art world.”

And it’s not just that it’s rather frowned upon. For all that Notte insists he’s not out to objectify women, he occasionally gets it in the neck for supposedly doing precisely that, perhaps especially as a white westerner painting ‘exotic’ women of a kind often fetishised by white westerners. He gets it – especially in the light of stories he’s often heard about artists having “awful”, somewhat one-sided relationships with their models.

“I’m just not sure there’s any way of getting around the idea that any painting of [an objectively beautiful woman] objectifies her,” he says. “It’s really bizarre”. It is, perhaps, the overly sensitive times we live in, in which everything is loaded with a pseudo-political undercurrent.

Homage to Jean-Michel Basquiat

“Basquiat stands as a key influence for a vast array of graffiti and street artists, myself included. His journey from early street tagging and poetry, to his explosion on to the contemporary art scene of 1980s New York, solidified him as the quintessential ‘cool artist’.”

Homage to Andy Warhol

“Warhol was one of the most successful and influential artists of the 20th century. In spite of criticism from the art world for his approach and capitulation to consumerism, Warhol’s influence has blazed across generations. I’ve included him and his work in my own numerous times over the years.”

Notte’s Asian portraits undoubtedly get more attention than the rest of his work. And he has certainly been committed to them. His manager once told him that it would be a wise business move to give them up in favour of painting rock and film stars and other more mass-market, cool-out-of-the-can images. “He was just trying to protect both of our careers,” Notte laughs.

Notte declined. “In fact, I wanted to prove that it would work.” So he upped the ante: adding a mask-like streak of colour across the eyes of his portraits – inspired by Daryl Hannah’s character of Pris in Blade Runner, and Annie Lennox’s early 1980s make-up – his subjects took on a superhero quality, a fresh fierceness and a defiance. ‘Objectify me and see what happens,’ they seem to say.

Or, to put it in the kind of nonsensical critic-speak that accompanies so much art, ‘the appropriating, colonialist male gaze is turned back on itself, the voyeur overwhelmed by an act of female empowerment’. The Frida Kahlo Foundation liked the idea so much they granted Notte sole rights to alter her image for a commissioned, 200ft high mural in Guadalajara, Mexico. That one took him 11 days to paint. He has, he adds, had to overcome his dislike of heights.

The mask move was also commercially smart, creating a marketable signature for his work. “Whether [the viewer] likes a painting or not, it needs to create an instant reaction in terms of its recognisability. And, of course, people who buy art want others to recognise that brand too,” he suggests. “Is that cynical? No, it’s why you buy a nice sofa too. We’re bombarded with marketing all the time, like it or not. A lot of artists – and a lot of companies – don’t seem to figure that out.”

Homage to Frida Kahlo

“Another piece that’s an homage to both artist and muse – albeit that they are one and the same. Being confined to her bed for long periods of her life owing to her spinal injury, Kahlo became her main muse and this piece is a recreation of one of those self-portraits.”

Enter ‘the new Banksy’, as Notte has come to be labelled. Enter, too, Phillips auction house selling one of his original works, painted on gesso panel, for an artist auction record of £50,800 last year. And finally enter – perhaps most importantly to Notte – healthy sales of prints of his work. This is all the more necessary since, well, it’s not easy to sell an apartment block wall – and all of his globe-trotting is self-funded.

It’s having worked in “brain-washing” advertising that Notte both understands its mechanisms and seeks to avoid their influence over his work. If it might be argued that an artist needs to engage with the world, he rarely knows what’s happening in the news, and isn’t a fan of social media. Perhaps, again, this is a product of his late blossoming – that eagerness to follow his own merry way.

“What’s going on around me seeps into whatever I’m doing. I love engaging with people, and with the environment [in which I’m working],” he says. Though he admits that, while he works in silence, meditatively, he often wears earphones to stop him being asked too many questions.

“The fact is that street art has allowed ‘normal’ people to interact with art, and have an opinion about it, without feeling that it’s in some way inferior [to the kind found in a traditional gallery setting]. And that’s my engagement with the world, interacting with everyday people, out on the street, painting”.

Rankin

London calling

After our initial interview, square mile caught up with Fin DAC again ahead of his new exhibition in London called HomEage. Showing at Crypt Gallery St Martin-in-the-Fields from 25-26 October, the exhibition brings together 24 original works paying tribute to icons of the art world.

SM: How did HomEage come about?

FD: It started in 2020 in California, during the first Covid lockdown, as a positive time-wasting exercise: painting pieces on paper so that I could take them with me back home whenever the world opened up again. It started with my four favourite artists: Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Patrick Nagel and Francis Bacon who was replaced quickly by Julian Opie.

SM: Whose style was most difficult to emulate and why?

FD: Probably Pablo Picasso because that style is so opposite to how I work and unique even to this day. I definitely decided in the early part of the project to not even try certain artists but then reconsidered later on, as I grew in confidence, with the different styles and techniques.

SM: Were there any you started and scrapped because the style just didn’t gel – or for another reason?

FD: As mentioned previously, I decided against paying homage to Francis Bacon – my second favourite artist of all time – simply because the darkness of his work didn’t feel like it fitted, and I didn’t want to force it. I painted Warhol twice (two years apart) as I wasn’t happy with the first version. But I’m a perfectionist so it was bound to happen at least once. I gave the first version to a friend.

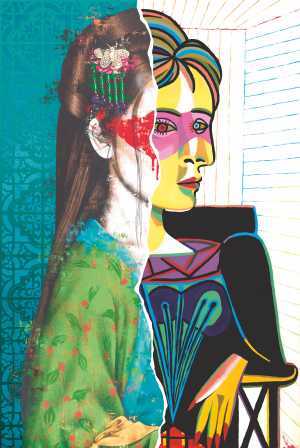

Homage to Pablo Picasso

“I chose Picasso for this collection because of his importance to the art world in general and because I really wanted to have a crack at something completely outside my comfort zone. Also, as with some previous pieces in the collection, it was another opportunity to pay homage to both artist and his muse Dora Maar.”

SM: Do you have a personal favourite piece from the collection?

FD: It’s a toss-up between Jean Michel Basquiat, Julian Opie and Kitagawa Utamaro… really hard to choose as they’re favourites for very different reasons.

SM: We’ve heard that you’re a reluctant exhibitor – why is that?

FD: Being the centre of attention in those surroundings is not really my cup of tea. I’m aware that creates quite the contradiction, given the inherently public nature of my street works, but I’m more comfortable painting murals.

SM: Were you surprised by the success of your 2021 Afterglow/Undertow exhibition?

FD: Absolutely. I hadn’t done a solo exhibition since 2015 and, in the interim years, I had spent more and more time on the road and not particularly focussed on my gallery output. It took a whole year to produce over a hundred artworks.

I can’t deny it was a very satisfying feeling seeing the public response to all the new styles and new directions as some were quite a departure from what people would have been used to.

Homage to Jamie Reid

“With this particular artwork I was able to posthumously pay respect to two giants of British design: Jamie Reid who was the man behind the look and feel of punk graphic design and his sartorial counterpart Vivienne Westwood. Sadly, they passed away within a few months of each other.”

Homage to Julian Opie

“My initial introduction to Opie’s work happened through my love of music and in particular his striking cover art for the British band Blur. I later got to appreciate the original artwork up close and personal at the National Portrait Gallery in London.”

SM: Which contemporary artists do you most admire – and why?

FD: That’s such a difficult one for me to answer because there’s so much work to admire out there and my tastes change constantly. But the darkness and delicacy of Ozabu is always appealing, as are the watercolours of J Hunsung.

SM: Talk us through the process of making one of your street works – from location to logistics?

FD: Most of the time I’d decide where I was going to travel to and find walls along the way. It was very simple and organic. Most of my murals I painted at my own expense.

The most interesting parts for me were working with buildings that I could adapt or use a piece of the architecture to inform the design and working out a colour scheme to suit a location. You get quite used to being able to sort things all by yourself when you’re on the road for six months a year.

SM: You’ve had commissions from the Royal Albert Hall to Red Bull, Armani to G-Star – can you talk us through some of your favourites?

FD: I don’t think anything can compare to the Royal Albert Hall. Possibly nothing ever will. To be able to paint street art, and sleep overnight as part of the process, in such an iconic, world-famous venue was a bizarre and brilliant experience.

Duke of Westminster in North Wales

“Freezing temperatures, howling winds, and driving icy rain should have made this a miserable experience. And yet, in spite of my seven layers of clothing and spray cans seizing because of the incessant cold, this was, and still remains, one of my favourite projects.”

SM: Your Bang & Olufsen speaker cover for the company’s iconic A9 speaker sold out in record time. Do you have any more collaborations in the pipeline?

FD: One potentially massive project for Ibiza next year but nothing’s been signed yet so I don’t think I can reveal a name.

SM: Is there a brand or designer you would particularly like to work with one day – and why?

FD: Adidas for certain. I’ve been an avid collector for years and at one point had more than 200 pairs. That had to be reduced when I moved last year as my new apartment wasn’t large enough to house them all.

SM: Travel is a huge part of your work. Is there anywhere you’ve loved so much you’d consider moving there – and why?

FD: The top two would be Japan or New Zealand. I’d love to do a big project in Japan just so I could live there for a year or so. It’s such a vastly different place to anywhere in the west that I’d love to experience it more than I have.

SM: Where are you off to next?

FD: Next up is Medellin, Colombia followed by Tahiti and then on to Louisiana. That will be the longest trip I’ve been on since 2020, so I’m looking forward to it.

SM: You once said “There is no reason to sit down and relax, the most important thing is the work”. You must switch off some of the time, right? Any guilty pleasures?

FD: Honestly, it’s a rarity for me to relax. Even if I sit down in front of the TV, after an hour or so I’m generally asking myself “Why am I doing this?”. I don’t think I would call them guilty pleasures but I really enjoyed Blue Eyed Samurai on Netflix and My Neighbour Totoro live show at The Barbican this year.

View on Instagram

For the prints, book and collectors’ card set, see west-contemporary-editions.com