They say never go back. Presumably ‘they’ aren’t one of Britain’s most celebrated actors returning to the role that made his name. In 1997, David Harewood became the first black actor to play Othello at the National Theatre, a groundbreaking production starring Simon Russell Beale as Iago and directed by Sam Mendes. Nearly 30 years later, Harewood revisits the Moor at the Theatre Royal Haymarket opposite Toby Jones’s delightfully malign Iago and Caitlin FitzGerald as a feisty Desdemona.

There is much to discuss beyond Shakespeare, not least the two documentaries that Harewood has fronted in recent years. Psychosis and Me examined mental health via the psychotic breakdown that Harewood experienced in his early 20s, while 1,000 Years A Slave saw the actor grapple with the enduring legacy of slavery – his ancestors were enslaved on a Barbados plantation owned by the second Earl of Harewood. David’s portrait now hangs in Harewood House, the stately home built from the profits of the slave trade.

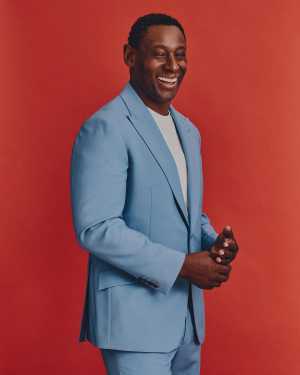

I met Harewood in Balham. Nearly 60, he combines a teenage enthusiasm with remarkable eloquence and insight.

Square mile: It’s fair to say you have a long history with Othello…

David Harewood: It’s the third time I’ve played it. The first time was at the Swan Theatre in Worcester. And I remember my agent saying, “Play it out of town because at some point you’ll play it in town.” And she was absolutely right because about ten years later, I was the first black actor to play it at the National. It’s kind of in my bones.

I was saying to our director Tom Morris the other day – I have zero anxiety. Normally a big Shakespearean part, you’re thinking about it. I’m more excited, there’s no worry. I know the emotional map of it, so I’m just really excited about the journey that I’m about to go on.

SM: Do you approach the play differently as an older man?

DH: Very, very much so. That insecurity, that worry that he talks about. What has really amazed me, reading the play again, is how quickly he falls for it.

SM: We did an essay on that in A-Level. ‘Why is Othello so easily manipulated?’

DH: What did you think?

SM: It was a while back. So Iago doesn’t plant the seed of violence in Othello; he draws out something that’s already there. That violence is already within him.

DH: He’s got a vulnerability. His own innate vulnerability makes him susceptible to the idea that he’s being cuckolded. I think he defines himself primarily as a fighter, as a soldier. And suddenly he’s not.

He’s in a world of love. He just got married. He’s happy for probably the first time in his life. He talks about the inner joy, how much joy she gives him. But it also makes him very vulnerable because suddenly he’s got this Achilles heel. And that Achilles heel is his ego, a warrior-like spirit.

Immediately he starts to define Desdemona as the enemy. I think that’s his default position of winning, of being successful, of not being defeated. And the minute she dies, the mist begins to clear a little bit. At the end of the play, he does kind of return to that magnificence and goes, ‘Fuck, I’ve thrown a pearl away…’ He knows he’s done a really, really bad thing. The only way out is to top himself.

SM: “Loved not wisely but too well.”

DH: Too well, yeah. That makes him vulnerable. As most men are, he’s kind of insecure. We talk about toxic masculinity – there’s an element of Othello where he’s an insecure man and the minute Iago starts talking to him about the idea of Cassio, he can’t get it out of his head.

At no point does he go, “Let me speak to her.” It’s immediately, “Set on thy wife to observe.” He’s instantly in that world of, ‘I need to find out what’s going on, I need to check her out.’ He immediately gets to that default position of, ‘I’m going to find this out, I’m going to win this battle.’

As opposed to, ‘She can’t do this to me – I’m the great Othello.’ His masculinity, his ego, gets in the way of having the humility, having the humanity, to sit down and talk to her. I think that’s a common trait of men.

SM: Iago as a manosphere influencer is a great idea. He probably would be today…

DH: That’s one of the things that we were talking about. When we looked at the play, Toby was almost, ‘Why are we doing this play? It’s horrible!’ We all sat down and thought, ‘How do we tell this story in a post MeToo world, in a post Black Lives Matter world? What’s it saying?’

What’s really exciting in our production is we’re empowering the women. So Desdemona is much stronger. She’s older, she’s very strong – as opposed to this young virgin. She’s much more front-footed. That’s going to make it a much more fiery, combustible relationship. Same with Emilia. In the play, these two are very put upon. The production will examine why these women put up with the bullshit.

SM: Emilia gives Iago the handkerchief that he uses to frame Desdemona…

DH: Exactly. Why does she do that? Even though she knows he’s a bit of a wrong’un, she still fucks up by giving him the handkerchief. So we’re trying to find a reason why these women make these decisions. Othello slaps Desdemona in the play, and we are looking to find if there’s a place where she can slap me. If I called my wife a whore, she’d probably beat me up.

We’re looking for ways of making the women much stronger. That makes it really exciting – if it’s not such an easy path to their destruction. She loves him. And if you love your husband, if you love your partner, you’re going to fight for it. So we’re looking for ways to make her fight for her love, a little more than perhaps other productions have done in the past.

SM: What made you return to the play? Were you approached?

DH: I was, yeah. I had no intention of returning to Othello again. It’s not something that was on my radar. Tom and Toby Jones were thinking about doing the play and who they would have as Othello. My name came up. My agent rang me up and said, “Would you have any interest in playing Othello again?”

I’d just finished playing William F Buckley in the West End, Best of Enemies, which was so much fun. I hadn’t been on stage for ten years since doing Supergirl. And I loved it so much, I thought, ‘I want to do that again. I want to be in the West End again – and I want to get on stage again.’ So I said yes almost straight away.

I read it again, realised how much I still remembered of it, recalled how much I loved the play, and it was an immediate ‘yes’ – especially when I met Tom and the idea of doing it with Toby was put on the table.

SM: Your previous Iago was Simon Russell Beale, right?

DH: Yes, that’s right. I’ve had two fantastic Iagos. Historically I guess there’s always been friction or competition between the two parts, but the better actor you get for the part, the better play you get.

SM: What are your memories of that historic 1997 production?

DH: I remember it really well. I remember being extremely nervous. Obviously I was so aware about being the first black actor to play Othello at the National. I was so conscious of it. Maybe I was trying too hard, trying to be as authentic and real as I could be – which worked really well, but I haven’t got the energy to do it like that now. This time around, I’m much more relaxed about it.

I understand the emotional map of the play. Rather than carving out a whole new way of doing it, it’s just ‘How am I going to do it?’ So there’s more excitement around exploring the part. Last time, it was a real journey for me; emotionally, mentally it was tough to do and tough to explore. This time I don’t feel that because I know it; I’m just excited about the journey.

SM: Are there any particular lines or scenes you’re excited to revisit?

DH: A couple. We did a working week last year, four or five actors reading the play and looking at the text. And I was amazed how much I remembered. I hadn’t read the play in 30 years but so much of it, I was off book, I didn’t need to look at the text.

Whereas before I was trying to be really authentic, really trying to reach for the emotions, really trying to reach for the feelings and stuff. During this read-through, I had to stop myself from becoming emotive. The language is so beautiful, how he talks about her is so beautiful. That speech to the Senate where he says, ‘Let me just tell you what happened, how I met her, let me tell you how I fell in love with her.’ It is such a beautiful speech.

He’s so confident at the start of the play, he’s so strong. To think that this man, by the end of the play, becomes almost animalistic. It’s a great journey to go on, from high to low. By the end of the read through, everybody was in bits. I was like, ‘Where’s this emotion coming from?’ Because it wasn’t there when I did it last time; I had to sort of reach for it.

When he starts to doubt, he says, “I am declined into the vale of years.” I’m 60 now. I know what it’s like to be older. I know how my body’s feeling. Physically I am not capable of doing things that I could have done 30 years ago. So there’s a slight ‘in’.

Also as a black actor, I look at the fantastic actors now getting opportunities that just weren’t open to us 30 years ago. So there’s a slight envy of their youth, there’s a slight envy of the opportunities that they have. And I certainly didn’t feel that last time as I was quite close to the top of the tree. So there’s that idea of time passing, of things moving away from you.

I was working with this wonderful American writer last year and we were talking about turning 60. He said, ‘We’re in the third act of our lives.’ The three-act structure. The second one starts around your twenties and thirties. The third act is resolution. I’m in that resolution phase where things get tied up.

I’m getting towards the end, and I naturally feel that as a 60-year-old man. We’re going to be on stage during my 60th birthday. It’s the first birthday that has real significance for me, turning 60. That’s a biggie. I can understand the character feeling jealous, totally with someone like Cassio – this handsome, young dude. The jealousy of youth, the energy of that youthfulness. I can certainly attest to that.

SM: My dad’s a little older than you. He said that mortality is an abstract concept when you’re young. You don’t really believe you’ll ever die – whereas by his age, you do.

DH: Thirty years ago, I didn’t understand that element of it. Whereas now I fully understand that element of being older. Also the idea of beauty and being in love, being vulnerable – I don’t think I really understood that.

SM: Even at 30?

DH: I was a bit of a heartbreaker. I was still being a bit of a lad. Now that I’ve had kids, I guess I do understand love and vulnerability. Look, I cry at school plays, kids singing Christmas carols and stuff like that. It just makes me weep. It’s that idea of freshness in youth – I fully, fully understand that now, more than I did in my thirties.

SM: I watched Psychosis and Me, the brilliant documentary you made about being sectioned in your twenties. Do you think exploring that period of your life has influenced how you approach the play?

DH: Massively. But I think the last five or six years of my life have been the most [pauses]… it’s almost like I don’t recognise myself before that. Before making that documentary. It’s hard for me to watch that documentary now; it’s like looking at somebody else.

The revelations have come as a result of that documentary, the exploration that I’ve done on myself, finding out about my past, finding out about why my breakdown happened, really examining aspects of my life. Most people don’t get the opportunity to do that and they probably don’t even feel they need to do it. But for me, that excavation has really revealed something. I probably know myself more now than I’ve ever known myself. Ever.

Getting in touch with my vulnerabilities and doing it so publicly… I didn’t realise when I was making that documentary, I was giving people a real look into my life and soul. I wasn’t prepared for the overwhelming amount of people who almost thanked me for that. They came up to me in the street and engaged me on it.

Even though it was a traumatic experience, I’ve gone through the trauma. A friend of mine said, ‘You’ve found post-traumatic growth’ – as opposed to traumatic stress. Embracing that vulnerability and embracing my weakest moment – the breakdown – that’s really led to a much more thorough understanding of self and people.

That’s why I think playing this part at this stage of my life, after breaking yourself in two, it’s going to be much more… I wouldn’t say ‘easier’ but it’s going to be a more authentic version of myself on stage.

SM: One of the few ways that society has unambiguously improved since the 1990s is the understanding of mental health.

DH: It’s become much more of a public conversation. People have started to acknowledge it. I’m glad to have played some part in breaking down those barriers. To this day, people come up to me and talk about it. So it’s obviously done some good.

SM: You’ve had such a varied career. Looking back, are there any roles that feel like game changers?

DH: Certainly Homeland was a game changer because it broke the American market for me. And I couldn’t get arrested here for a good couple of years. It was great to find a second wind in the States, which set me up for this third act. I’m genuinely excited about the stuff that’s to come.

For the first time in my career, I’m not worried. Maybe that’s where you get to in life, I don’t know. I’ve done a tremendous amount of work already and now it’s time to be picky, enjoy the fruits of my work, and choose the path I want to go down.

SM: You’ve got a biblical epic coming up?

DH: Biblical epic shot in Morocco. It’s called Zero AD. I play Balthazar, one of the three kings. To be part of that was quite extraordinary. There’s also Pierre, my first TV lead in the UK. I play a duty solicitor. I feel great about where I’m at. I’m pumped!

SM: A Balthazar is also a massive bottle of champagne – so you know how to celebrate your 60th. Are you religious yourself?

DH: I’m more spiritual than religious but I certainly had an experience on that film. Whatever it was, I came away full of beans. So I’m just glad to have been a part of it.

SM: Finally, I watched another documentary of yours, 1,000 Years a Slave. I’d never realised your surname derives from Harewood House in Leeds. The Lascelles family owned the plantations where your ancestors once worked as slaves – now your portrait hangs in the house itself.

DH: It was really tough but really worthwhile. I went back to Barbados and examined the reality of life in Barbados. Then I interviewed David Lascelles [8th Earl of Harewood]. He’s a Buddhist, so he was very calm and I’m thinking, ‘I want to get into this.’ Eventually I said to him, ‘Do you feel guilty?’ He said, ‘I don’t feel guilty because I wasn’t responsible but I can be accountable.’ I thought, ‘Wow, great answer.’

I think he’s the first Lord Harewood that’s been honest about where the money came from. There’s lots of literature in the house about it. And he engages fully with the arguments about reparations and things like that, which I thought was commendable. So it was well worth doing.

People, particularly black people, have said good on you for putting a face to all those who have had no face or had no history. When people go around Harewood House, they see the magnitude and the fineness of the house, they stumble upon my picture. They’ll realise slavery has a living, breathing legacy. It’s the people whose names are taken from their owners.

It’s not just in the past for me. It’s a living, breathing history. Four generations – my great, great, great grandfather. He was Richard Harewood. You see the family tree and it’s literally just four generations. You get my dad and then me. You just think, ‘Wow. It really wasn’t that long ago.’

View on Instagram

View on Instagram

Othello is on at the Theatre Royal Haymarket from 23 October 2025 to 17 January 2026. Get your tickets here