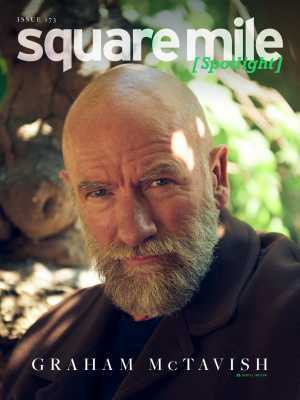

It’s a scorching summer’s day in Regent’s Park. The parched brown grass bears testament to the ongoing heatwave, as do the sweaty pink faces of the passing pedestrians. Leaning against the trunk of a small tree, Graham McTavish gazes into the middle distance. He wears a hefty woollen overcoat and a pensive expression (possibly musing on the wisdom of the hefty woollen overcoat).

Half concealed by overhanging branches, and a halo of leaves that glow a glorious green in the afternoon sunlight, the brooding McTavish looks like a man out of time, a druid who happens to shop on Savile Row. Our photoshoot proceeds undisturbed but, were someone to accost its protagonist, you’d get even money on whether they’d ask for his autograph or request the recipe for a magic potion.

But then Graham McTavish specialises in playing men out of time – or rather, men of times other than this one. He enjoyed his first serious success as Vincent Van Gogh in his self-penned two-hander Letters from the Yellow Chair. He trod Middle Earth as the dwarf Dwalin in Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy. He led a Scottish warrior clan through the Jacobite rising in Outlander. He will shortly head to the fantasy medieval continent of The Witcher – but first he will command the Kingsguard as Ser Harrold Westerling in highly anticipated Game of Thrones prequel House of the Dragon.

Even the notable McTavish roles set in the present day – such as villainous turns in Preacher and Lucifer – still venture beyond the mortal realm. In Preacher, he was Heaven’s personal hitman; in Lucifer, he got possessed by a demon. “I don’t tend to get the chance to play thoroughly decent human beings,” notes McTavish with some understatement.

Ser Harrold Westerling is an exception. “He is a straight arrow,” says McTavish. “A shining beacon of decency having to deal with these plotting individuals.” And even then, the knight is a “‘don’t mess with him’ kind of a guy.” (True of most people who own a sword.)

Why, I wonder, is McTavish so rarely cast as a straight arrow? “I’ve got one of those faces,” he says with a chuckle. Apparently he resembles his father, “and my dad always looked quite intimidating so I’ve inherited that resting expression that he had.” He stands six foot, three inches with a shaven head and a beard so fearsomely masculine it probably attends MMA classes and bristles at the slightest hint of provocation. Were you to be stood outside a pub and spot Graham McTavish advancing towards you with purpose, you would be forgiven for advancing with even greater purpose in the opposite direction.

In truth, he is a softly spoken man of great charm and depth. In the hypothetical pub scenario, he’d likely be coming over to solicit directions to the local art gallery. He loves drawing. He wrote adventure stories as a teenager. He travels – boy, does the man travel! He was born in Glasgow, joined the amateur dramatics society of the Surrey village of Frimley, attended university in London and now resides in New Zealand. There was also a childhood stint in Canada, where eight-year-old Graham watched Neil Armstrong take the most famous step in human history.

“The most significant thing that’s happened in my lifetime,” says McTavish. “You can’t beat a man landing on the moon. Everything else is a variation on something else that’s already happened.”

Like the man, our shoot is peripatetic, encompassing not only a stroll through a sun-dappled Regent’s Park but also a stint at The Coach Makers Arms – a splendid Victorian pub and restaurant – as well as a visit to Paul Rothe & Son delicatessen, established in 1900. (So also Victorian, just.) Pub and deli are Marylebone institutions and stand within sight of each other. McTavish was very taken by the deli. At the end of our interview – conducted in the pub, naturally – I saw him crossing the road to offer it further inspection, and quite possibly custom. (I had one of its salt beef sandwiches for lunch: delicious.)

McTavish had minimal interest in acting growing up. “I used to perform my own comic sketches with my friend but had no interest in ‘acting’ acting at all.” Perhaps these sketches were the reason why a drama teacher enlisted a 17-year-old McTavish for the school production of Georgian comedy The Rivals. He was a late replacement – like, three days before curtain raise late – and had always rejected the drama teacher’s overtures. This time he assented – “it was probably because I fancied a girl in the cast or something” – and inadvertently found his calling. “It went really well and people laughed and applauded and that was enough for me.”

Several plays are central to McTavish’s story: “crossroad moments”, as he calls them. The first Scottish production of Death of a Salesman in 1990 and its 1992 revival; McTavish describes the latter as “by far the best production I’ve either been in or seen… I was so glad and proud to be a part of it.” There followed another Dundee production, A Long Day’s Journey Into Night opposite David Tenant. The great Brian Cox (himself a Dundonian) saw the show and subsequently summoned McTavish to London for a role in Richard III. “That was a big change for me. And that was a huge endorsement from him.”

Spool back further and we reach Krapp’s Last Tape, chosen by a 23-year-old McTavish to get his equity card because “if you did a one-person performance, it counted as a variety act and you could get in on an easier route.” The young actor toured his show around the pubs of London, pubs like The Coach Makers Arms. Naturally, the occasional mishap occurred – such as the night that McTavish couldn’t get the tape to play. (He was about to cancel the show when he realised he hadn’t turned the volume up.)

One night, there was only one person in the audience. Since there was only one person on stage, you could reasonably describe the staging as ‘intimate’. Nonetheless, McTavish did his best to entertain the lone punter and then invited him for a pint afterwards.

“What did you think?” he asked his audience in the pub downstairs.

“It was good,” said the man. “It would have been better as a radio play.”

McTavish smiles ruefully at the memory. “An hour of my life I’ll never get back!”

His career would soon take a turn for the spectacular – and the surreal. (OK, technically the post-impressionist.) McTavish and his friend Nick Pace wrote a two-man play about the Van Gogh brothers. They took it to the National Gallery, an institution which had never staged a play in its entire history. “For some reason, best known to themselves, they said yes,” recalls McTavish. “I think they almost instantly regretted it.”

Over the summer of 1986, McTavish and Pace embarked on an unrelenting and very successful publicity campaign. Too successful for the National’s tastes – as McTavish notes, “they wanted to be seen to be doing things but they didn’t want them to be too popular because then that gives them a lot of work. But this became hugely popular. We sold out the entire run of the play in 15 minutes. It became a little bit of an embarrassment to them that people literally couldn’t see it.”

Someone suggested they take the play to the art galleries of America. The pair were keen but contacting American art galleries from London was easier said than done in 1986. Aside from its switchboard, the National only had one external phone line – handily, the phone it connected to was housed in the lighting booth of the lecture theatre where the play was being performed. McTavish and Pace wrote to every art institution in the States, included the number of that phone and sat by it. As the letters were written on National Gallery-embossed paper, it didn’t take long to ring.

“We booked an entire tour of America from a lighting booth in the National Gallery,” says McTavish with understandable pride. They didn’t stop there: “We did three tours of America, a tour of Australia, a tour of Canada, tours of New Zealand and Europe.”

Like I said earlier – peripatetic.

Last year, McTavish received great acclaim for a new role – that of Graham McTavish. Men in Kilts is a travel documentary helmed by McTavish and his friend Sam Heughan, the star of Outlander (and two Square Mile covers).

The first series, which followed the duo travelling around their native Scotland, received critical acclaim, numerous award nominations and even spawned a bestselling book. The sequel will take place in New Zealand, where McTavish now lives.

Men in Kilts is a true labour of love: McTavish and Heughan came up with the concept in Los Angeles and shot a pilot in a matter of weeks. Their first idea was a podcast. “Then we were gonna do GoPros,” recalls McTavish. “I don’t know how that would’ve worked. One on my head, one on his? It was a ridiculous idea. And then we just said, ‘why don’t we just get a film crew together?’”

The scenery is stunning but it’s the odd couple interplay between the two Scotsmen that gives the show its tartan heart. “We are very well suited,” says McTavish of Heughan. “We’re very different in lots of ways. He’s kind of like my unruly teenage son and I’m his grumpy dad, in a weird, weird way. I mean, technically I could just about be his dad.”

View on Instagram

Last year, Heughan was interviewed for Square Mile by Tom Ellis, the star of Lucifer (and one Square Mile cover – so far). Both men took great pleasure in discussing their mutual friend McTavish and the first series of Men in Kilts. “It is a slightly dysfunctional relationship,” said Heughan. “We bicker quite a lot but I think that’s the joy.

“Graham plays these characters who are quite masculine, quite aggressive. He’s a character. He’s well built. But in real life Graham is a total teddy bear and extremely nervous around dangerous things. The joy of Men in Kilts was getting him to do things that he didn’t want to do.”

“Is he scared of heights and stuff like that?” asked a clearly delighted Ellis.

“Oh yes,” said Heughan with equal enthusiasm. “He’s terrified of heights. I got him to abseil. He refused point blank to get in a kayak with me despite trying to bribe him in every way. I got him on a tandem bicycle but he complained about that incessantly.”

“I imagine Graham’s language probably gets quite colourful when he’s scared,” said Ellis, the affection audible in his voice.

The show isn’t scripted: all colourful language is entirely their own. “It is me and it is him,” says McTavish. “We know who we’re gonna interview, we know where we’re going and that’s it. Everything’s very spontaneous and organic and surprising, as surprising to us as it is for anybody else. And that’s what makes it fresh and fun.”

As for a hypothetical third season? “The logical place would be North America.” McTavish speaks with a conviction that suggests he and Heughan have given the matter some thought. “Because there’s such a massive Scottish influence there, Canada and America.” Take Montana: “the McDonalds of Glencoe moved to Montana. I met their ancestors while I was filming there. They’re native American – so you meet this native American guy called Rob McDonald.

“There’s a whole history of how the Scots arrived. And there are many, many, many more stories to tell about the huge influence that the Scots have had, as such a tiny nation, on the world that we know, especially the English-speaking world.”

And should their road lead through Los Angeles, perhaps Tom Ellis could make an appearance. He’s Welsh but I’m sure they could lend him a kilt.

As you may have gathered, McTavish is a man with a considerable hinterland. “Graham is such great company and he’s got so many stories,” noted Ellis in the conversation with Heughan. “I do love his Sylvester Stallone impression as well, it’s very funny.”

I don’t hear his Stallone voice (McTavish appeared in the first Creed film), but I am told a quite amazing anecdote about McTavish, Mads Mikkelson, Mike Tyson and Tom Kenny sitting in a bar. Now for those who don’t know, Tom Kenny is the helium-pitched voice of Spongebob Squarepants. Mike Tyson did know this – and duly started doing Spongebob impressions to a slightly bewildered Kenny. I can’t speak on the quality of Tyson’s Spongebob but you suspect it could have sounded like Darth Vader and everyone is clapping regardless. (McTavish didn’t relate whether Kenny responded with his Mike Tyson; somehow I have my doubts.)

But McTavish offers more than a good yarn. He can speak with authority on Scottish clans or James Bond films – yes, he’d love to play a Bond villain, “that would be a lifetime ambition come true” – or the novels of JRR Tolkein and George McDonald Fraser, to name but two who arise in our conversation. (Thirty years ago, he’d have made a brilliant Harry Flashman.) At one point, he quotes Albert Einstein: “Computers are useless. They only give you the answers.” And yes, when writing up this profile I discovered the quote is more commonly attributed to Pablo Picasso but the sentiment still stands.

Fame and fatherhood found McTavish relatively late in life. The latter occurred in his forties. “It completely redefines your whole world,” says McTavish. “And it does profoundly affect you as a person because your horizon changes. Your horizon is no longer just there in front of you, just stretching away. Your horizon is your children. Everything is seen from behind them.”

Fame is harder to quantify but his most notable screenwork all occurred in the last decade. “Well, it’s very odd,” says McTavish, a little self-consciously. “Anybody that’s had a career as long as I have – which is nearly 40 years now – you’ve had many, many, many iterations of success or lack of success, disappointment, joy. You’ve gone through the whole gamut.”

As such, McTavish can speak on his profession with no little perspective – indeed, ‘wisdom’ might be the appropriate noun (one I’m sure he’d hate). You be the judge. He sees his recent work as “no more or less meaningful than many of the things I did in my twenties as an actor. It just so happens that those things were seen by a tiny number of people. And the things that I’m doing now are seen by millions of people. But I don’t think that affects the quality of either – they’re just different.”

Quantity is also important – every actor fears unemployment. “I remember Paul Newman saying that he was always expecting somebody to come and tap him on the shoulder at some point in his career and say, ‘I’m so sorry. We’ve made a terrible mistake. You’re awful. You’re terrible.’ It’s very ephemeral, acting. You can measure things like music: somebody can play the violin well or they can’t. Somebody’s obviously a good dancer or they’re not. Acting is a much more subjective art force. And so I think that instils a great deal of insecurity among the practitioners.”

This magazine has featured numerous actors who found success at a young age, and several of them have spoken of their imposter syndrome – not despite early success but because of it. McTavish nods, unsurprised. “On the plus side,” he notes, “It gives you a little bit of a sense of humility. Good actors, really good ones, have a very self-critical mind. Bad actors tend to be people who just think they’re really, really brilliant. They have no idea. They just blunder along and some of them are very, very successful. I’ve worked with some of them.” (No, I didn’t bother asking which ones. Forty years in the business breeds a certain discretion.)

His need for reassurance has dissipated over the years, whether through success or maturity. Both seem to be increasing with age: McTavish will follow House of the Dragon by facing off against Henry Cavill in The Witcher. Cavill is another Square Mile cover and a “thoroughly lovely bloke.” (We like to think the two are mutually dependent.) He’s also very tall. Like, very, very tall.

“He’s a big chap,” says McTavish. “I am taller than him. Just want to point that out.”

Really? (Since our 2018 interview, Cavill has grown in my memory to resemble a sort of humanoid double-decker bus.) “Oh yes,” says McTavish with more than a hint of twinkle. “I’m about an inch taller than Henry. Just saying. Obviously, we haven’t had an arm wrestle yet but I have high hopes. He has huge thighs. Not that I was fixating on his thighs but they were just so large. I didn’t mention it to him. But he’s got a great, great sense of humour. And also, which I think is a good mark for anybody, he’s curious about the world and other people.”

A description that applies to Cavill but also to McTavish – albeit the latter’s curious mind is a whole inch higher above the ground.

McTavish’s father died before his mother. In the funeral home, alone with her husband, she told him a very simple and beautiful thing: “You promised me a life of adventure, and you gave me one.” Which of us would not cherish such a goodbye? Got me a little choked up when I read about it – “it gets me every time as well,” says McTavish.

Terribly morbid question for a sunny Friday afternoon but what parting words would he like from his loved ones? “Oh gosh,” he says. “I want them to think of me as someone who’s always done my best and always tried to make them happy. And given them everything I could.” The grace, says McTavish, is found in the shared journey – “and at the end of that journey, to be able to look back and think it couldn’t have been better. And it’s not about it being great all the time. It’s about the journey. It’s about the completion of that journey.

“It’s not like my parents’ life was one long round of roses. But they stuck it out and went through it all together and had three children and saw their grandchildren born and all the rest of it. I think that’s the most that any of us could hope for – to see that circle of completion in our own life.”

His circle is far from complete. I expect the arc that lies ahead of him will be equally as remarkable as everything that has come before. The next adventure awaits.

As featured in the magazine

Watch House of the Dragon on Sky Atlantic.