Moments after grabbing his arm in a distracted manner, Mark Gatiss stiffens in his seat, widens his eyes in mute horror, and folds forward onto the desk, lifeless. It’s never a great start when an interviewee expires within minutes of their appearance, although at least Gatiss soon returns in spectral form so my trip to Nottingham mightn’t yet be in vain, provided I can source an ouija board.

Relax, relax, it’s a play – like Gordon, Gatiss is very much alive! (As an adolescent of the 1980s, and a lifelong geek, he’ll appreciate that reference.) Not only is Gatiss alive but Gatiss is thriving, with three projects out this December alone: an updated version of children’s classic The Amazing Mr Blunden, another BBC ghost story in The Mezzotint, and his stage adaptation of A Christmas Carol – now playing at Alexandra Palace. As another noted polymath once observed, “he who isn’t busy being born is busy dying.” Mark Gatiss achieves rebirth on a regular basis, even if he’s currently perishing on a nightly one.

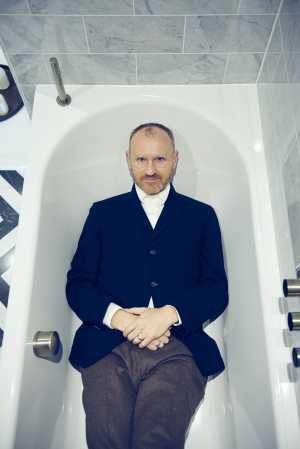

The man I meet for breakfast the following morning is as far from ghostly as anybody could be. I’d say Gatiss was on good form but it’s 9am on a Tuesday – for all I know, this could be power saving mode. If so, imagine him when fully charged. Over a freewheeling hour and a half, he sings a 15th-century carol, quotes verbatim from Charles Dickens, Rodgers and Hammerstein, and James Bond, reels off the ages of early Doctors Whos, dates of past by-elections, adopts various accents with the ease of an aristocrat slipping on a pair of suede gloves, and rarely lets a sentence pass without some exclamation of mirth – a wry smile, a mischievous giggle, a laugh that could awaken the dead.

Gatiss doesn’t work on shows so much as brands: Doctor Who, Sherlock, Dracula. He writes, he acts, he directs, stage, TV, film, radio, books – a master of multiple trades in an age where some aren’t even a Jack of any.

“What I always get is ‘Renaissance man’,” says Gatiss, “and I always say, ‘well, so was Cesare Borgia.’”

Envisage Gatiss and you will likely envisage his Mycroft Holmes: a suavely reptilian figure, as calculating as he is cold-blooded. (This description also applies to his Peter Mandelson.) The real thing is a much sunnier prospect (acting, dear boy), if not entirely divorced from the on-screen persona. Scanning the menu, I comment wolfishly on the Lobster Eggs Benedict. Cue a raised eyebrow from my dining companion. “Lobster, for breakfast?” says Gatiss with the merest hint of reproach. “Faaar too rich for me.” I opt for avocado on toast.

Shall we start with the carols? During A Christmas Carol, the Cratchit family sing the Wassail song – “here we come a-wassailing, among the leaves so green” – and in the stalls I thought of my late grandparents and singing the same words around their dinner table. (It’s that kind of evening: it takes you back, it takes you home.) During rehearsals, Gatiss was transported back to his own schooldays when the actor Christopher Godwin began singing the medieval carol ‘The Boar’s Head’.

“When I was seven or eight,” recalls Gatiss, “our teacher decided as part of the Christmas service at the church we would sing this old carol.” Cue a tuneful rendition of the first verse – “The boar’s head in hand bring I / Bedecked with bays and rosemary” – and Latin chorus. “Caput apri defero, reddens laudes Domino…”

The class even made a papier mache boar’s head to parade up the aisle, only for their teacher to decide “it’s not good enough!” and scrap the performance. Nor did ‘The Boar’s Head’ ultimately make A Christmas Carol; ‘Oh Come All Ye Faithful’ is there, closing the entire show on the proclamation “oh come let us adore him, Christ, the lord.” For a secular society, it’s an interesting choice.

“Yes, it is, isn’t it?” agrees Gatiss. “I’m an atheist but one of the reasons the story has always resonated so much with me is that its Christian message is a genuine Christian message. As opposed to the one which pretend Christians bang their drum about.”

He chuckles when I quote Mycroft, dismissing heaven as “a fantasy for the credulous and afraid.” Yet carols are bound up in even an atheist’s national identity. “It’s the complicated relationship with being English, isn’t it? That you are moved by listening to ‘Jerusalem’ but at the time people are very muddled about it all. Patriotism is the last refuge of scoundrels and you don’t want to wrap yourself in any kind of flag, particularly at the moment. But it presses deep buttons.”

So does his Christmas Carol. Impeccably staged and performed, with a brilliant Scrooge in the form of Nicholas Farrell, the production is heavy on phantoms and ghouls, more than earning its subtitle ‘A Ghost Story’. But what else would you expect from this horror obsessive – a man whose childhood was spent in the shadow of a Victorian madhouse…

Not quite, according to Gatiss. That particular biographical tidbit is a slight case of ‘print the legend’ – “one of those Wikipedia things that’s now impossible to get rid of. It was a perfectly ordinary mental hospital, built in the 1930s, which in popular imagination has now become like Arkham Asylum.

“I always used to slightly roll my eyes to the idea that it influenced me. But I think now it must have done. Of course it must have done! My dad worked there and we grew opposite it. We used to do everything there. We used to get our hair cut there, we used to go swimming there, we used to go to the cinema there. And it was perfectly ordinary to us to be surrounded by mentally ill people and I think that must have an influence over me!” The end of the sentence dissolves into a fit of giggles.

Pass, psychiatric hospital. Sort of. OK, what about my favourite scene in the play: when we are Christmas Past-ed to Scrooge’s childhood, see his devotion to books over human friendships? “I wasn’t quite alone; I had company.” Gatiss quotes the script. “I’ve always loved that idea.”

Does he relate to it? Again, sort of – only TV was his primary inspiration. Old films, Ripping Yarns. “I was always interested in macabre, horror. I never wanted to play outside; I always wanted to stay and watch the telly with the curtains drawn. All the clichés!”

And unlike Scrooge, he had a school friend. “We were sort of inseparable and we lived in a world of imagination. Doctor Who, horror, stuff like that. But I didn’t take refuge in it because of loneliness. I was just obsessed with stories and fantasy and books.”

They lost touch, Gatiss and his school friend, but recently reconnected on Twitter – “which is very strange after all these years. It’s a long time.” But as A Christmas Carol attests, it’s never too late to reach out. Gatiss recently discovered a Chinese proverb; the words resonated so much he cites them in the programme notes. “The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second best time is now.”

His first professional tree was The League of Gentlemen, the late-1990s sitcom centred on the village of Royston Vasey. Clever, surreal, morbid – all the Gatiss calling cards were present. So too was the humanity, the heart. “The big League characters are very human monsters,” says the man who would later introduce Count Dracula to the concept of wifi. “They have an element to them that is very relatable, really.”

Human monsters, macabre humour: if a writer as prolific as Gatiss can claim a manifesto, that might be it. In his own words: “It’s a combination of pathos and grotesqueness, comedy and horror, all mixed together. The things I really love, and really affect me, tend to do all those things at once.”

The show won a Perrier award, a BAFTA, a film – but Gatiss cites the 1999 Montreux Rose d’Or as the moment he realised the League had come into their own. A writing session was interrupted by a phone call from Paul Jackson, then head of BBC comedy. “Go to Heathrow.”

A car was summoned. “We all piled in. It was like an episode of Jason King. Nothing was booked. We had to go to the desk and say [dramatic baritone], ‘I’ve got to get to Geneva tonight!’ We flew to Geneva and then got a car to Montreux.” On their arrival, the waiting Jackson handed over a huge wad of Swiss francs. “You’ve won,” he said. A delighted Gatiss phoned his parents. “Guess where I am!”

Incidentally, Jason King was a short-lived 1970s spy series whose title character helped inspire Austin Powers. You must be a demon at a pub quiz, I tell Gatiss. He grins. “People often try and get me on quizzes. I love a pub quiz! I don’t do TV ones though cos they’re too scary. I’m afraid of going blank.”

If the League was the first tree in what has become a very bountiful orchard then Sherlock remains the tallest. Gatiss and Stephen Moffat’s modernised take on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle proved almost as popular as the original, racking up an audience of millions, multiple awards, countless fanfictions, global syndication, and springboarded Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman from respected TV actors to bonafide film stars. (Andrew Scott hasn’t fared too badly, either.)

“It was an extraordinary thing,” says Gatiss. “We were very pleased with it but we had no idea what would happen. Benedict became a star overnight, like something from a Hollywood movie in the 1930s.

“It’s amazing to be part of something where that happens. But you can’t bottle it. All the planets aligned at the same time. That’s what happened.”

Sherlock-mania reached its peak with the second series cliffhanger: Holmes jumping to his death from the roof of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, only to reappear seconds before the credits rolled. For two years, a nation attempted to deduce the mystery of his survival. Forums buzzed with theories. The views on YouTube videos entitled ‘How Sherlock Faked His Death’ were matched only by the comments beneath them.

Gatiss chuckles when I mention The Fall. “I watched videos of people working it out and I thought, ‘this is extraordinary.’ You can never then actually, I suppose, please people. We did all those fake versions but we never really say how he did it. Because people just go… meh.”

Tongue firmly in cheek, the season three premiere supplied several potential solutions – a bungee cord; Derren Brown! – without ever settling on a definitive one. But come on, Mark – it’s the airbag, right? Has to be the airbag…

“Yes, there is an explanation. But it’s never absolutely confirmed because otherwise you’re left forever going, ‘oh, OK.’ There’s a newspaper in ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ – as Dr Watson turns it over, it says ‘refit for historic hospital.’ And it’s actually a picture of Barts with scaffolding outside it. There are a couple of things like that.”

Which is fair enough, although you can understand the frustration felt by certain fans at the perceived lack of closure. (But it’s the airbag. He’s confirmed it’s the airbag. Let’s move on.) For Gatiss, the imagination invariably trumps reality – even a reality he gets to script. Take crossovers. “People used to always bang on about Doctor Who and Sherlock meeting. But the version that people have in their head will always be better than what you do.”

I mention a fan-made video, ‘Wholock’, that depicts an encounter between Matt Smith’s Doctor and Sherlock. Ten million views, rapturous online reception… “Yeah, it’s very good,” nods Gatiss. “Let’s leave it at that, then.”

One of the joys of Sherlock is identifying the references made to the wider Conan Doyle universe. The season two finale even toyed with one of the all-time great fan theories: that Moriarty – never met by Watson (and thus the reader) in ‘The Final Problem’ – is actually a figment of Holmes’s drug-addled imagination. A 1980s’ play, starring Jeremy Brett and Edward Hardwicke, explored this premise. A young Mark Gatiss went to watch. Thirty-odd years later, he takes great pleasure in reenacting the curtain calls for me.

“Edward Hardwicke came on and gave this very neat little bow. Gatiss stands up and demonstrates in the middle of the restaurant. (Still empty, alas.) “There was a long pause and then Jeremy Brett came out like this!” He twirls down into a bow an Elizabethan courtier would consider a touch florid.

Last year’s Dracula had a fleeting reference to Holmes – “a detective acquaintance in London” – but an encounter seems unlikely. Still, there’s partial overlap. Two days into filming the third series, Gatiss, Moffat and producer Sue Vertue attended the RTS Awards.

“I had a picture on my phone of Benedict silhouetted against Mrs Hudson’s door, the episode where he comes back. I said, ‘he looks like Dracula’ – and the then head of drama said, ‘do you want to do it?’ We laughed and it didn’t go away as an idea.”

Any plans to return to Sherlock? I pose the question as our breakfast arrives. “Never say never,” says Gatiss, tucking into his eggs on toast. “Not at the moment, though.”

He loves the Victorian era – Dickens, Dracula, Doyle – but Doctor Who is his first and perhaps greatest love. He’s written multiple novels, scripts, appeared in several episodes – but unlike his regular collaborator Moffat, this lifelong fan hasn’t yet run the show. Has he ever been approached for the job?

“I haven’t. I’ve seen up close how much toll it takes. On anyone. It’s like the England job, isn’t it? It’s impossible. You’re trying to please everybody whilst you’ve got three million people sitting behind you, every day of your life, telling you what you’re doing wrong and why they’d be better at it.”

I struggle to believe Gatiss would reject the showrunner gig if offered – but the question is moot for now due to the shock return of Russell T Davies. “It’s incredible,” says Gatiss of Davis’s comeback, inevitably dubbed RTD2. “The last person I thought would ever do anything like that! I’m intrigued as to what he does. Because everyone has a version of what they’d do with Doctor Who – but he’s already done it! So now we’ve got the tantalising prospect of another go. It’s extraordinary!”

OK, but Davies will need a Doctor – and surely Mark Gatiss, a mercurial, fiercely intelligent actor with more than a touch of the alien to him, would make a splendid regeneration for the departing Jodie Whittaker? The suggestion earns a smile.

“You’re very kind. I think that ship might have sailed. When I was little I used to think of nothing else!” He laughs, then reels off the ages of past Doctors on their debut. “It was an older man’s part – even when they went younger with Tom Baker, he had a different kind of gravitas. The radical change was Peter Davison. It was such a bold and brilliant thing to do to make the Doctor 29!”

Breakfast finished, coffees ordered, the conversation turns to Bond – the last great bastion of British pop culture that Gatiss is yet to storm. And while he isn’t nominating himself, Gatiss believes the series should be overseen by an auteur, similar to Christopher McQuarrie on Mission Impossible. (Gatiss has an undisclosed role in Mission Impossible 7.)

He has an idea for a Bond film. He and Moffat workshopped it over dinner a few years back. “Stephen was really under the cosh with Who and we were under orders not to talk about Doctor Who or Sherlock – it was like a night off. So of course what we talked about was James Bond.”

They came up with a story, something that hadn’t been done before. Gave it the working title All The Time In The World. “It was quite nice, I think,” says Gatiss, softly. But then, he notes, very little of their script would likely survive its exposure to the studio system. “You go to all the thrill of being part of Bond, only to realise that you were one cog in a very big machine and you’re going to get overwritten.”

He doesn’t share the details of All The Time In The World – never say never, after all – but it’s a fair bet the film would be a lighter outing than those of the Daniel Craig era. “What they need to do is respond to the tenor of the times, which are bleak as fuck, and give us a bit of Rog again. That doesn’t mean they have to be out-and-out silly. I think they need to be lighter – they need to find a lighter actor – and have a bit more fun with it.”

He asks my choice for Craig’s successor.

“Me? God knows…”

“God’s busy,” comes the immediate retort.

Next Bond is a tough one – maybe Regé-Jean Page – but Idris Elba would make a fantastic villain. Gatiss shows me a video on his phone of his husband Ian Hallard on the Thai island Khao Phing Kan – the hideout of The Man With The Golden Gun himself, Francisco Scaramanga. “We went to Thailand just before the pandemic, and made a point of going to Scaramanga’s lair.”

We discuss past films and favourite plot holes. At the climax of Spectre – “a very boring film!” stage-whispers Gatiss – Bond enters a derelict MI6 building to be confronted with photographs of deceased enemies plastered over the walls. “I thought to myself – who photocopied those? Was Blofeld in Rymans or did he have somebody to do it for him?”

We agree the Craig films became too serialised, and No Time To Die was far too long. “Almost everything is too long,” sighs Gatiss.

That’s why I appreciated the relative brevity of A Christmas Carol: two hours, everyone out before 10pm.

“I’m gonna call my autobiography, ‘Ninety Minutes Straight Through.’”

In certain contexts that’s quite an impressive runtime…

“Chance would be a fine thing!”

We move onto politics via A Christmas Carol and its message of kindness and redemption. “I wish I could beam it directly into Priti Patel’s brain,” says Gatiss of the play. “I do wonder if someone like Jacob Rees-Mogg came along tonight, I imagine they’d go [toff] ‘Oh it’s the most wonderful thing, British tradition, it’s marvellous!’ and yet completely miss the point of it!”

Such is the ubiquity of the story, “it feels like it’s been with us forever. But it was published, and people reviewed it. People complained the title didn’t make sense and all these Daily Mail type reviews. But there are recorded instances of people doing stuff: a couple of factory owners gave their employees the day off and gave them all a goose. They were properly pricked by it.”

He isn’t anti-Tory, despite throwing an egg at Michael Heseltine during the 1983 Darlington by-election. “Heseltine came to press the flesh, and he was the face of the fucking enemy then! Now? John Major, Heseltine, Chris Patton – these people look like giants!” He is most certainly anti-Brexit and anti-Boris Johnson. “The fish rots from the head down. And he is infecting everything with his absolute mendacity. It’s incredible. It’s incredible the effect it’s having on every level of society. It’s like a poison in the system.”

Queues at petrol stations, a shortage of key workers, sewage in the water supply – the effects of Brexit are already being felt, even if nobody wants to acknowledge the cause. “Oh there’s this weird supply issue with lorry drivers. What could have caused that?” says Gatiss with magnificent disdain.

“I’m a cock-eyed optimist, to quote Rodgers and Hammerstein, and I feel beaten down by the current state of this country, I really do.” In ten years, “what is it going to be like? It’s literally already overflowing with shit! Literally overflowing with shit! What kind of water do they want to drink? They’re gonna want to get it imported. They can’t! There are no fucking lorry drivers!” Cue a cackle of laughter at the absurdity of it all.

Serious question, and I want a straight answer – did you hit Heseltine with that egg? More laughter. “I honestly don’t remember! I wish I could remember that. Probably not. I’ve always been a bad thrower – I’m a gay!”

Let’s not end on politics – it’s Christmas, after all. Let’s end on Bob the dog, the beautiful fox-red Labrador who is the background on Gatiss’s phone. “I miss him very much,” sighs his owner. “He’s staying with his grandparents at the moment. I don’t like being away from him.”

He’s also pro-cats but is adamant: “you can’t quite trust someone who doesn’t like dogs. That’s a life lesson. And secondly, they are the best thing you will ever have. They are a daily joy. It’s like having a fool – there’s a reason that kings and queens used to have fools. It’s a good idea. They bring something to you that’s really life-enhancing. They really do. And that’s my lesson.”

We say our goodbyes and part ways, me to the train station, Gatiss off to prepare for another evening of spreading the Christmas spirit. His work may be wreathed in darkness but as a person he is all light.

The Mezzotint will air on BBC Two. The Amazing Mr Blunden will air on Sky Max. A Christmas Carol runs at Alexandra Palace until 9 January 2022.