The first thing you notice about Tom Rhys Harries is how relaxed he is. The 29-year-old wanders up the stairs of the Soho members’ club and offers a disarmingly spacey smile. His phone is playing up; the Cloud is demanding a password, as it always does at inconvenient times, so he’s apologetically distracted. It doesn’t stress him out, though: this is a man rarely in a rush.

His phone fixed, Rhys Harries takes his seat in the empty bar and sips his sparkling water. He is wearing a hoodie and tasteful-if-unflashy jewellery, pulling off the kind of stay-at-home chic that creative types manage so effortlessly.

He recently appeared alongside Uma Thurman for Apple TV’s Suspicion. He is about to return to the Harold Pinter Theatre (a venue he knows well after starring in Mojo in 2013 with Ben Whishaw, Rupert Grint and Brendan Coyle) to play Trigorin opposite Emilia Clarke’s Nina in Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull. Laidback doesn’t mean you don’t work hard.

The Welsh actor is no stranger to household names for colleagues. He’s worked with Benedict Cumberbatch, Baz Luhrmann, Jez Butterworth, Hugh Grant, Charlie Hunnam, and Matthew McConaughey in a career that started with a fresh-faced Rhys Harries in Indie films and off-West End plays. In 2012, he was recognised alongside Tom Holland as one of Screen UK’s Stars of Tomorrow. Ten years later and Rhys Harries mightn’t yet have the global fame of the Spider-Man actor, but he’s well on the way to becoming a star of today.

His curiosity and openess to the new is palpable. Our conversation has barely started before he’s asking me about shorthand and how I write an interview. He tells me he’s a keen pianist and guitarist and that he aims to release music one day. This is clearly a man in love with the creative process in all its forms.

Acting has been a part of the Welshman’s life since he was a child. Indeed his earliest roles were in Welsh. “My dad was a headteacher at a Welsh-language school,” he says. “A lot of my early acting was in Welsh because that’s how it was with school productions. I love going back home to work. I did this thing called Hinterland where you record it all in English and Welsh.”

In 2020, Rhys Harries enjoyed a major breakthrough with a starring role in Netflix’s drug-fuelled whodunnit White Lines. Imagine a crossover between Death in Paradise and New Tricks where everyone’s on cocaine. In Ibiza. That’s White Lines. Unsurprisingly the show proved very popular, hitting Netflix’s top slot in more than 20 countries.

Not that Rhys Harries was phased. He tells me: “I guess you sort of have an awareness of the reach of a project but it’s not useful to dwell on that. With Netflix you’re there in people’s living rooms – there’s insane access.

“I worked with this actor called Kit Connor a couple of years ago on a Simon Pegg and Nick Frost film [Slaughterhouse Rulez]. I think he was 13 or 14 at the time. But now he’s just had Heartstopper come out and overnight he’s got 3.5 million followers on Instagram. It’s insane. That kind of instant feedback hasn’t really existed before in any media before streaming. It’s uncharted territory for the entertainment industry.”

Acting on Netflix has been quite the experience for Rhys Harries, especially given the complexities of his character in White Lines: he plays pre-murdered sociopath Axel Collins, seen only through other characters’ recollections of him.

“You’re playing a memory,” he says. “The need then is to think what does that character who remembers you wants to remember? Our memories are so flawed in terms of missing the truth about a person that it was really fun to experiment with that.

“I just think what does the story need me to be and what does that character that’s remembering need me to be? When you’ve got a story arc like Axel with that kind of fall from grace I think there’s a danger of endgaming it.”

Despite all his effort to shape his character’s development, Rhys Harries fears it can sometimes be in vain. He explains: “In a TV show like that, things can be sort of out of your hands because it can be edited and you lose control of that arc that you’ve tried to create.” He trails off with a tone of what could be well veiled frustration.

Coat: Nicholas Daley | Trousers: Descente | Boots: Grenson

It has probably become apparent by now that Rhys Harries is unshy about dropping huge names into the conversation. “I shot Parade’s End with Benedict Cumberbatch.” He catches my eye to note my reaction. “It was around the time Sherlock had come out so he was everywhere. I had a tiny part but it’s taken from this massive book that’s wider than it is tall.

“I had one line that just didn’t sound right to me. I don’t know who the fuck I thought I was, but I went up to the director and I told them ‘I don’t think this is right.’ They looked at me like I had something growing out of my ears but didn’t contest it.”

He continues: “Just before they made a decision on it, Benedict popped up with the book and said he’d had the same concern as me, but that he’d checked the book and it was right. It was so telling to me that he knew even this tiny part so well. He’s so studious in his work and just a brilliant actor.”

While the pressure of working with such big names may be intimidating for some actors, Rhys Harries brushes it off. He says: “It’s just cool getting to watch what makes people tick. Especially people like Guy [Ritchie] who’s a real icon of British cinema, and it’s often not what you’d expect.” (Rhys Harries had a cameo in Ritchie’s The Gentlemen as Power Noel.)

“Directors can be so bombastic, especially film directors who are considered auteurs. I worked with Baz Luhrmann a few years ago and a lot of these directors are just amazing to be around, absolute forces of nature. I think at the core, they feel very authentic to themselves, and you’re just watching them being given room to explore that. My takeaways from the great directors I’ve worked with would be you’re the only you you can be. You’re never going to create something, a character or persona, that is more rounded and full than you yourself are – what your real interests and core thoughts and feelings are.”

Coat: Givenchy | Jacket: YMC | Trousers: Sandro | Hoodie: Huel | Shoes: Grenson

Away from acting, Rhys Harries is hoping his recent move out of London will give him a good excuse to get back into another passion: biking. “I love doing manual stuff,” he says. His gaze wanders up and he fiddles with his ring. “I’ve ridden bikes for years but one conked out at the start of the pandemic and I just never replaced it.

“It’s like an antidote to what I do for work. Acting is so subjective and sort of heady but there’s nothing subjective about whether an engine works or if a sprocket’s out of place.”

When Rhys Harries is on his bike, it’s all about the gears and the throttle and the million and one factors ensuring that you remain on the road. The “fiddly shit,” as he calls it. It relaxes him, all that energy that goes into keeping everything going.

Finding solace in the complex has been a fixture in Rhys Harries’ decade on stage and screen. He lives with ADHD, a condition that was occasionally tricky in his school days. “I was quite disruptive growing up,” he admits. “I don’t think I was ever malicious but I didn’t always know what to do with myself and often that energy came out in having fights.

As so often in tough times, salvation came via the kindness of others. “I was so fortunate with really strong, protective and nurturing women in my life when I was growing up. They had my back but also were just incredibly patient with me when I was badly behaved. There’s one teacher who I’m still in contact with now. I wouldn’t have finished school without her and that isn’t lost on me.”

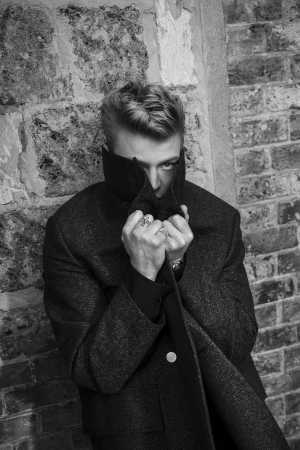

Coat: Jil Sander

Rhys Harries’ ADHD has bled into his approach to acting: “I don’t know any different so I don’t know the alternative, but I know that I’m shit at focusing on something if I’m not interested in it. Then if I am interested in something, I get obsessed with it, because it’s kind of a relief to be able to focus.

“I’ve always had that focus with acting because it’s scary. The impulse to distraction is quietened by the fear of being criticised. I think I was aware from quite a young age that fear was a big driving factor for me.”

That obsessive focus is apparent in Rhys Harries’ approach to his latest role. The Seagull was supposed to be performed at the Harold Pinter Theatre in March 2020, but after a full rehearsal process and preview performances, Covid intervened.

“I put the script down at the start of lockdown and hadn’t opened it until three of four weeks ago,” he says. “Reading it again was so bizarre. I knew all of it before lockdown and I wanted to see if I had retained the lines. I hadn’t in the way I thought I would. I couldn’t remember any of the words, but I remember how it felt being in that character.”

Ian McKellen once compared acting Chekhov to climbing a mountain while tied to your fellow mountaineers; the Russian dramatist’s work is famously challenging for actors. For Rhys Harries though, the depth of The Seagull is what attracts him to it.

“The reason I love Chekhov’s work is that there’s so much going on below the surface if you scratch away. It’s kind of autobiographical but veiled in this structured play.” Here his eyes are as wide as when he was speaking about motorbikes.

“That’s particularly true of The Seagull. It’s almost like Chekhov’s having a therapeutic dream that’s spilled onto the page and created The Seagull. There’s loads to be pulled from getting to know where Chekhov’s head was. You start asking why are you saying this? Why do you need to say this?”

At this point Rhys Harries gets contemplative. He’s placing Chekhov within his own relationship with acting when he says “plays aren’t written for monetary gain; the good ones are written because the writer has a compulsion to write the thing. They need to get it out. And then when you have someone like Chekhov who is skilful enough to vomit any kind of emotion that they need to get out, or story, or message, then you have a play.”

Rhys Harries grins. After two years without the theatre, here is an actor ready to speak to his crowd again. “You can’t tell the audience what to think,” he says. “If the thing is good, you just have to be the character and let the audience interpret things. You can never tell them what to feel.

“That’s the amazing thing about theatre. It’s that symbiotic relationship between the actors and the audience and the text. It’s one of our oldest communal things. It’s gathering round the fire and hitting drums.”

That’s the note Rhys Harries leaves me on. I ask him if he has any dream roles but he bats the question away. The world doesn’t need to see his Hamlet, he explains. Shakespeare has no real pull for him. It’s about the story. A good story, a character to dive into and Rhys Harries is there.

For now, however, he’s happy tinkering with his motorbikes.

View on Instagram

The Seagull will run from 29 June to 10 September at the Harold Pinter Theatre.