“Are you not entertained?”

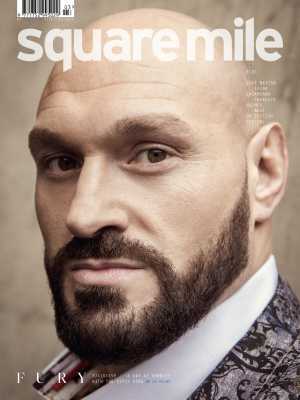

World heavyweight champion Tyson Fury is holding court at Wembley Stadium. He’s addressing a heavily attended press conference ahead of his much anticipated fight with Dillian Whyte at the same venue in April. It matters little that Whyte has failed to turn up to the conference himself as Fury is capable of giving the cameras and collected journalists more than enough of a buzz on his own. At six foot nine, wearing one of his trademark flamboyant suits, he dominates the stage – and the sport.

“I’ve got a new name for him, it’s Frillian Whiteknickers,” he says of no-show Whyte, before posing for a face-off on his own. Fitting for a man who has had to face himself and his own demons, which have surely been more of a challenge than any opponent he has had to fight in the ring.

“He should be kissing my feet and washing my feet,” Fury says of Whyte at one point, referencing the Brixton fighter receiving the biggest payday of his career.

If you listen to Fury speaking for any period of time, you’ll notice Biblical references peppered into his speech, and it’s clear that this is the foundation of his mental strength today. The world heavyweight champion often balances trash talk with a reverence for God and his faith. He has frequently attributed his phenomenal journey back from depression, demons and addiction to his steadfast belief in his religion.

Those who stand in the dark can never come into the light

On battling suicidal thoughts, Fury previously said, “I didn’t care about boxing, I didn’t care about living, I just wanted to die… Jesus came to my rescue”.

And after stopping Deontay Wilder in 2020, he opened with some passionate words: “First and foremost, I want to say thank you to my Lord and saviour Jesus Christ. I said those who bring evil against me will never prosper, I said those who stand in the dark can never come into the light, all praise be to the one and only true God, Jesus Christ.”

For the record, I’m not a specialist sports journalist. Over the past few years my focus has been interviewing men from all walks of life about their various trials and tribulations, and how they have overcome them. This was for the award-winning Modern Masculinity series which I produced and hosted for the Guardian. One episode explored the world of UFC and featured interviews with fighters Darren Till, Kelvin Gastelum and Jorge Masvidal.

But for years I’ve been fascinated by Fury. On this journey, Tyson Fury has been one of the names that has constantly been referenced by men who I have spoken to about their struggles with mental health and depression, and it’s clear that his legacy is much greater than that of his career in the ring. Many men have found a role model in him and his story.

So, when Square Mile asked me at short notice to spend some time with him behind the scenes at the press conference for their April cover interview, it didn’t matter that I was out of the country in France. I dropped everything and took the first Eurostar to London and headed straight to Wembley.

“My faith is unshakeable. Without faith we have nothing”

Behind the doors of the conference room, where many journalists are starting to set up their cameras ahead of the press conference, Tyson has an impressive entourage – including both his dad John and brother Tommy – all in good spirits and enjoying free reign of the locker room where they’ve congregated. Cameras flock around him as he poses for photos on the pitch. I have been promised a short slot with him between his other media commitments, ahead of the presser.

After a bit of banter – “You won’t get too hot if I take my jacket off,” he jokes – we settle down on some physio beds on the far side of the changing rooms. Sitting across from him as he puts his feet up, I can’t help but think of the scenes from The Sopranos where Tony speaks with his psychiatrist.

With limited time we cut to the chase and I ask just how important his faith is to him. His demeanour changes instantly and he grabs the chance to speak on the subject:

“My faith is unshakeable,” he says, not missing a beat. “Without faith we have nothing. It’s a very big part of my life and it’s guided me throughout my whole career and it’s been the background and backbone for everything to me.” Even in his most difficult moments, he says, his faith remained resolute.

“I read this quote once which said ‘even in your loneliest times, you thought that I had abandoned you, but I carried you’ and I believe that when we experience tough times in our lives, it’s all for a real purpose.”

That purpose, he explains, is to be able to use his experience to help others struggling with their own mental health battles. So how does his faith appear in his day to day life?

Tyson and Iman kick back

“I’m not gonna lie about it,” he says with a hint of guilt, “I haven’t been to church in a minute or two, but I try and read a few verses a day and say me prayers and stuff like that before I eat or bed, or just walking down the street sometimes… Some religions pray five times a day, but I probably pray sometimes ten times a day. Not long things but just thanking Him. Thank-you prayers.”

This is something which he describes as being important for his whole family, but what is the most important lesson that he wants to pass on to his children?

Fury takes a deep breath and thinks for a moment before responding. “I think the biggest job that I have done is to teach my kids about religion, about God and prayers and stuff at a young age.” He’s also tried to instil a work ethic in them too.

“My father was a working man. He worked all his life and I worked growing up as a kid, and everything that I have I have worked hard for, but my kids are coming from a privileged background, their father’s a multimillionaire, a famous sportsman, so I don’t want my kids growing up thinking that money comes easy – I don’t want to spoil them.”

Religion has long since been linked to successful boxers. After defeating Wilder in 2020, Fury became the third heavyweight to hold The Ring magazine title twice. His predecessors Floyd Patterson and Muhammad Ali were both men of faith themselves, albeit different faiths.

Patterson said before their fight in 1965: “This fight is a crusade to reclaim the title from the Black Muslims. As a Catholic, I am fighting Clay as a patriotic duty. I am going to return the crown to America.” He was defeated by Ali whose pre-match trash talk included calling Patterson an “Uncle Tom,” a “white American” and a “rabbit”. By comparison, Whyte probably got off lightly with the nickname Fury gave him at the press conference.

All eyes on him

“It’s not how you go down… it’s how we rise again”

Like Ali, Fury has been criticised for his traditional views on women and religion. Hailing from an Irish traveller community in Manchester, Fury also shares humble beginnings and a strong sense of identity with the most famous Muslim sportsman of all time.

He speaks with pride about raising his daughter to help look after her younger siblings. The room quietens respectfully as he does.

“Some day she’ll have her own kids to look after,” he says. “I’m very proud that we’ve instilled that into our kids, to stick close to their grassroots and stay close to who you are and never lose yourself. Because at the end of the day, you can earn a few quid and have plenty of money and be successful in what you are doing, but if you lose who you really are in the beginning, your identity’s gone, then what good is it all to you?”

As Fury seems to like quotes, I’ve brought one along with me today by American self-help author Napoleon Hill – a somewhat controversial character, but whose words nonetheless remind me of Fury himself:

“Fear is the tool of a man-made devil. Self-confident faith in oneself is both the man-made weapon which defeats this devil and the man-made tool which builds a triumphant life. And it’s more than that. It is a link to the irresistible forces of the universe which stand behind the man who does not believe in failure and defeat as being anything but temporary experiences.”

A candid moment

Fury doesn’t know the quote but instantly identifies with it. “Of course, I make that bit true,” he says. “It’s not how you go down, or how you’ve been defeated, but it’s how we rise again.” Another reference to Christianity – the idea of rising again, which conjures images of how Jesus rose after his crucifixion, or a fighter climbing off the canvas.

Fury looks thoughtful for a moment. “You’re probably the first person who’s ever interviewed me who has spoken like this.”

I ask what he means. “Just speaking about religion, about faith, about believing in yourself and not being defeated.” But he is more than happy to stay on the subject.

“I think you’re never actually gone until you’re completely finished – until you’re dead – but you can come back from anything. I’ve come back from being massively overweight, totally mentally unwell, total mental health breakdown, being gone completely, and come back to being heavyweight champion of the world,” he says. “Not only have I done all that, I’ve helped millions of people along the way with their mental health, people in the dark, without a light.”

We continue talking for a few minutes before one of his PR team appears with a laptop, where someone is waiting for an interview from a media outlet in the United States. Fury switches instantly back into the Gypsy King, ready to give some snappy soundbites that will pack a punch and drum up headlines before the fight. This is, after all, the point of a press conference.

Tyson faces the press

“If you lose, you lose… The biggest pity is when you don’t try”

I excuse myself and go and sit down with John and Tommy.

Tommy is a little pale and admits that he is trying to get hold of some food because he has been fasting for more than 40 hours and is ready to break it. He politely sits on one side of me in the changing room; on the other side, John looks very content, pride visible on his face as he observes the action in the room.

While Tyson is giving an animated interview to a computer screen, other members of the entourage are milling in and out of the changing rooms. I’m happy to be sitting with John, though, who is just as compelling to speak to as Tyson himself.

“Let me tell you something, I was not me son, never was and never will be,” he says, leaning in. “But I’ve been a warrior all me life with a warrior’s mentality. I was always on the front foot. And I’ve taught these to be brave men no matter what they do. If you lose, you lose, but the biggest pity is when you don’t try.”

It’s hard not to feel uplifted by John’s energy. What has it meant to Tommy to have men like him and Tyson around to look up to his whole life?

“It means a lot having Tyson there,” he says. “Every single day, every single hour of training is to get to where Tyson is now, so having him there, actively fighting, seeing him in training camps, seeing how he handles everything is just motivation for me.”

As this interview has gone off-piste a bit – we haven’t really spoken about Tyson as a boxer, but rather as a person – I wonder if Tommy can shed any more light on his brother’s best qualities, qualities that people may not necessarily know about.

“I’d have to say something that a lot of people know about since he recently came out talking about it, but it’s his mindset,” Tommy says.

Iman and the Furys

“Tyson talks an awful lot about his mind, about how he approaches things, but I genuinely do believe that’s his best attribute, his best power. He believes that he can do absolutely anything and when he sets his mind to it, he does do it. He believes that he’s invincible and that’s the right mindset to have in this game, 100 per cent.”

Does Tommy believe that he’s invincible?

“One million per cent, made of stone,” he responds with a smile. Although he looks exhausted, his eyes sparkle. They are much sharper blue in real life.

I ask John the same question regarding Tyson’s qualities.

“He’s a very caring man,” says John, relishing the opportunity to speak about his son’s strengths beyond the physical.

“He’s a loyal person. He’s got a heart of gold and like I say, he’s got the strongest mindset I’ve ever seen in a sportsman in his field and that’s why he’s where he’s at today, because he’s a kind-natured man.”

John admits that at times he has questioned how far Tyson can go with his kindness. “He gives money away all the time to people who need it,” he explains. “I said to him only the other day, I said you’re giving away money to these people and you’re feeding their bad habits, you know, because there were drug addicts.

"He said, ‘you know what dad, I don’t care what they do with it, I gave it with a good heart. So what they do is their problem, I’ve done my bit but they can use it to go and buy food or do what they do, that’s not my concern. But I know why I’ve given it.’ He’s a lovely human being, Tyson.”

A natural showman

“If he were to fall, the rest of us would fall with him”

How hard was it for John as a father, when Tyson was struggling with his mental health and going through the challenges he faced during his breakdown?

“It was nearly over for the full family,” John says gravely. “It was almost over. He’s our main talisman, he’s the one we look to, he’s the mainstay of our family, he’s our beacon; if he were to fall, the rest of us would fall with him. I said, ‘when you go we all go’.

“We are a close-knit family and when one’s doing bad we’re all doing bad. The full family was in the biggest state possible for three years, nearly. We didn’t think he was going to come out of it, but it just shows our strength of mind: we said to one another, ‘right, let’s not let this thing beat us.’ We’ve been roaming this Earth now, the Furys, for 2,000 years – so why are we going to get beat now? Look what you’ve done, you’ve won a world title, you’ve done this, you’ve done that. Let’s not let this beat us because there’s a way out of it and the way out of it is helping yourself – and the B side is helping the world as well.”

John points out that with all of the headline stories happening in the world, underlying issues like mental health are not given the attention that they need. “The pandemic will come and go, mental health is here to stay and it’s getting worse. Only the other day near my house a young man of 19 threw himself off a bridge.” He seems genuinely pained. “Waste of life. It’s because it’s not talked about enough, there’s not enough support out there and it can all go wrong for a young person in 20 seconds flat.”

He explains there are steps that people can take when they get to this place. “Walking and talking, having the right professional people around you, that brought us out of it.”

John sees his role as being important in terms of providing support to his kids, well into adulthood. “As long as I’m alive, I’m the father and I’m the captain of my kids’ ships, I’m still the father. Tyson’s the king of the world but I’m still the father. I’m the creator so it’s up to me to say to them: dig in and find your inner strength, we’ve all got it, and use it.”

A proud father

Just sitting next to John, you can feel like he is bursting at the seams with life experience. He looks like a man who has seen and survived a lot of things, but he admits that he was worried about what Tyson might have done when he was in his darkest place.

“I said if you kill yourself it’s over for us,” he tells me, “because how do you get over that? You can’t get over that. And there are people out there who have suffered who have no choice but to live with it and I think about them every day. I think those people could have been helped.”

All of this focus on mental health struggles has made John think even more about the importance of being present as a father, and how a relationship between a dad and his son can be invaluable for guidance and purpose – for both parties.

“I’ve had a funny kind of a life,” he says, “and I say every day, if I’d have took notice of my father, I’d have had a better life. I wouldn’t have done the jail I’ve done. I’d have been a richer man, a happier man.”

It’s touching to hear him speak about his own experience of fatherhood. “You know the only thing I have done good in my life is be a good father,” he says. “You know the rest of it, it ain’t worth talking about but let me tell you if you’re there and you can keep advising and directing your kids you’re not doing anything wrong are you? And like I say it’s nice to be out of trouble isn’t it? If you’re out of trouble and you’re happy, you’re king of the world”

We’re just finishing when he adds a final word: “If I didn’t have these boys in my life, my life would be a dull and empty place. They brighten my days.”

Talk to the hand

“Today’s world is a crazy old world”

Fury’s PR representative comes to find me. He wants to continue our conversation once he finishes his current media call. A few minutes later, Tyson is back.

“You ready for round two?” he asks enthusiastically, “are we going back deep or skimming the surface?”

Happy to oblige, I ask him about his relationship with his dad and with that we’re off again.

“I used to wake up as a kid and see me dad going running down the road, hitting a bag, lifting weights so I was brought up around training and boxing,” Fury says. “So without that I wouldn’t be where I am today. That’s just a fact.”

John Fury is not in the room at this point. At various points in Tyson’s career, his father has been unable to be at his son’s side, most notably when he was sent to prison after a brawl in 2010.

“It’s good to be back and defending a world title here, and now me dad can be a part of it,” Fury says. “It’s good for him and it’s good for me.”

Even big men can look small

At some point John finds his way back into the changing room while we’re discussing the pride that he has for what his heavyweight champion of a son has achieved. “There’s eight billion people in the world and only two heavyweight champions, and that means just two dads. So they’re very lucky people aren’t they?” he says joshingly, knowing John is listening. “They’re very blessed and they’ve definitely got bragging rights in the local boozer – ‘my son can beat your son, my son’s world champion.’”

So did Tyson used to brag about his dad in the same way? “All the time!” he replies. This provokes a chuckle from John, now sitting just a few feet away. “He’s a good road-trip partner, he’s a good travel buddy, he’s a good everything.” Fury’s love for his father is obvious. He speaks at length about his admiration, attributing John’s newfound success on social media to his ability to speak to all sorts of people and draw them in.

“He has a story to tell, he has something to say that people will be interested in, he’s different, he’s a character” – John sounds a lot like Tyson himself to be fair – “he’s a blast from the past, he’s a chip off the old block, he’s a jack the lad, he’s a boyo, people want to be around him and listen to what he’s got to say and I find that interesting and intriguing.”

“When we go out he gets asked for more photos than me!” Fury adds. John basks in the glory, a huge grin on his face. We discuss the perils of social media – John’s presence on these platforms is relatively recent – causing young people to have unrealistic expectations from life. Father and son despair at the lack of “audacity,” “character” and “intellect” of a younger generation who rely on apps to secure dates rather than using good old-fashioned chat-up lines.

“Today’s world is a crazy old world,” Tyson Fury says with a shrug.

The joker

“There will be a fight forever…”

We are about to wrap up this part of the interview when I notice there are book covers printed on the cuffs of his shirt. His assistant and stylist Nav tells me later that they are a nod to Fury being a boxing historian; but my observation causes Tyson to mention that he recently read a book called Me and Christianity by C. S. Lewis – best known for his Chronicles of Narnia series. (Also religious allegories.)

“It’s a great book, written from the perspective of an atheist,” explains Fury.

“And he gets into religion and then he becomes religious and there’s other books where he loses his wife and becomes not religious any more… I like all that sort of stuff, it’s sort of my jam, what he writes about, so my mission in life is to read all the books that C. S. Lewis has ever done.”

What is their appeal to him? “Just like the realness of it, the deepness of it and just the truthful opinion from a stranger. Rarely do we find truth in today’s society,” he adds wistfully.

I put it to Fury that his honesty in speaking on his demons and dark moments is part of why he has resonated with so many people himself. After all, many in the public eye attempt to hide these sides of themselves, or only show them in a palatable way.

“Does it make us vulnerable or stronger?” he asks. I throw the question back onto him, adding that it perhaps makes it harder for people to pull the rug out from underneath him.

“If I was ashamed of all that stuff then it would give people the ability to use it as ammo,” he says, “but where I’m open, they can’t use that against me because it’s already out there.” Self-preservation wasn’t why he opened up about his issues in the first place.

“Men have a thing where they think you’re a weakling or a pussy if you talk about weakness. But if someone like me could talk about weakness then it could be alright for a normal person in the street to talk about weakness, and I knew that would be the case.”

Tyson takes his leave

Now we really are wrapping up the interview. The press conference awaits. Fury turns to one of the guys sitting nearby. “Guarantee all these things are going to be like, ‘how do you think the fight’s going to go?’, ‘are you going to train hard?’”

He makes a joke under his breath. “You know what,” he says, “it’s refreshing to speak to someone like her because the questions are just different. Out there we’ve got all the mainstream media and all the newspapers – every one of them will ask the exact same questions and there’s nothing different.” And with that we part ways, and Tyson Fury goes off to sell a fight on his own.

Fury has claimed that Whyte will be his final fight. One question from the press conference is what comes after the fighting? How will he spend retirement? “What I want to do after boxing is chill on a beach, drink pina coladas, drive Ferraris and live on boats and that’s it,” Fury tells the assembled media. “That’s what I’ll do.”

I also asked Fury this question, only the answer offered in the privacy of the changing room is more candid. “There will be a fight forever because I’m battling mental health problems on a daily basis so that will always be the fight,” he tells me. He’s reluctant to say too much else about life after boxing except to stress his desire to devote himself to home and family. “I’ve got six kids to rear up and teach good manners and respect for other people’s property and stuff. That’s a hard enough job without getting punched in the face.”

I get the impression that he doesn’t want to look too far ahead. Given the twists and turns of his story so far, that is quite understandable. We will have to wait and see what God or the universe or karma has in store for Tyson Fury next.

Subscribe to the magazine here

Tyson Fury fights Dillian Whyte on 23 April. Watch the event on BT Sport Box Office.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123. For more information, click here