Journalists don’t always get the best press. To some, you’re the stooge of the ruling elite, quaffing champagne with Murdoch and Mephistopheles on a superyacht. To others, your time is divided between hacking phones and ransacking dustbins.

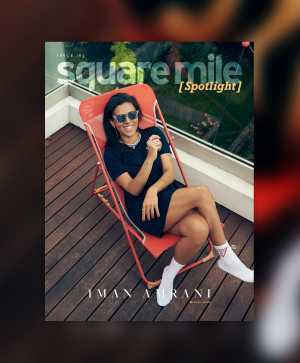

But there are still a few journalists whose work is greeted with universal acclaim, whose impact on the world is unquestionably positive. Thus Iman Amrani, creator of the Guardian’s award-winning series on modern masculinity and a solid bet to be the most interesting person around any dinner table.

Amrani is barely 30 and her life reads like an airport thriller. Aged 18, she found herself in the Dominican Republic during the 2010 Haiti earthquake and translated Spanish for the overseas doctors. She later combined teaching English at Bogotá’s Universidad del Rosario with helping out at a church in the red light district of Santa Fe.

While in Colombia, Amrani also worked social media to assist mothers who lost their sons during the escándalo de los falsos positivos, aka the ‘False Positives’ scandal: in which members of the Colombian military murdered impoverished, often mentally impaired young men and presented their bodies as guerilla fighters killed in combat.

Her first job at the Guardian? Flying to Kenya to work on a campaign to end female genital mutilation that won Editorial Campaign of the Year at the British Media Awards. (She had been on work experience the week before.) Following the Charlie Hebdo attacks, she filed video reports from the suburban ghettos of Paris, interviewing young Muslim men about the portrayal of their communities in the media.

“I would be allowed into those spaces off the back of my race,” Amrani tells me over tea at Shoreditch House. “I was Algerian. Also, probably the fact that I was a five-foot-three woman and unthreatening.” In her own words: “People open doors to me. They invite me in and they trust me and I see things.”

Bertie Watson

Amrani is one of those people who’s never still, even when seated; constantly shifting in the chair, illustrating a point with hand gestures, often erupting into laughter.

“I’m a bit of a black sheep,” she says at one point. “I know what I want to do and I’m quite driven on that. I try to do that with compassion and I try not to be a prick. I don’t think I am a prick. But I’m quite like an energy ball.”

Consider how she landed the Kenya gig for the Guardian. “I overheard on the last day of my work experience that they couldn’t get somebody to edit a video on the Monday. I didn’t even know what video editing was, I thought I was gonna be a print journalist. I just said, ‘I could maybe do that.’”

Deputy head of the desk was a filmmaker and journalist named Mary Carson. She knew Amrani was bluffing but liked her initiative. Amrani spent the weekend watching YouTube tutorials, returned on Monday and cut the video. The following week she was on a plane to Kenya after the original journalist dropped out.

“I was in the middle of nowhere,” she recalls. “There’s no way the Guardian would ever let anyone do that now. Mary Carson was breaking all the rules. It was great!”

Bertie Watson

Bertie Watson

Remember the opening paragraph? Funnily enough, Amrani is no more enamoured with her industry than the average commentator below the line. She refers to her early years at the Guardian as “the end of the good days of journalism”, and I don’t think the statement is tongue in cheek. Her mentors include the likes of Joseph Harker, Gary Younge and Randeep Ramesh.

These heavyweights showed Amrani that journalism was more than a viral tweet; that difficult questions don’t have simple answers, even if simple answers bounce louder around the echo chamber.

“I’m quite youth focused on some things but I’ve learnt to respect the power of real journalism and how important it is to document where we’re actually at – and hopefully move us forward. Rather than just churn stuff out that is meaningless.”

Her take on social media is scathing. “It’s divided the conversation. We don’t listen. We don’t read. We don’t spend enough time trying to really understand stuff. It’s so reactive.” And yes, she has Twitter – she’s a millennial journalist, there’s little choice – but primarily uses it to share articles and videos rather than spicy hot takes.

The Modern Masculinity series was created to cut through to the social media noise. Introducing the first episode, Amrani notes: “as soon as you mention men and masculinity online, the discussion becomes extremely partisan and really polarised. Post #MeToo, it’s even harder to talk about these things but more necessary than ever.”

Bertie Watson

Her perspective on the more extreme discourse surrounding #MeToo is characteristically nuanced and worth quoting at length. “If I’m being totally honest, I felt really uncomfortable with the conversation that was going on. I felt like there were grey areas. I felt like there were uncomfortable conversations we needed to have. But like everything else that seems to happen on social media, the conversation is not very real, it’s not very authentic, it’s quite performative.

“There’s a punitive, quite aggressive, almost revenge-driven way of looking at this. Which on one level I totally understand but at the same time the stakes are so high now. You’re not really inviting people to take accountability or responsibility. Now, if you did anything wrong, your career is over. That’s no incentive for people to come forward and have an honest conversation. People are terrified.

“Don’t be a prick. Don’t hurt women. Don’t hurt men. Don’t hurt anyone! But the conversation wasn’t necessarily done in good faith and I think a lot of people found it to be quite cathartic, and I did not find it cathartic.”

Modern Masculinity attempted to broaden the discourse. That first episode examined the Jordan Peterson phenomenon; “I want to look at why Jordan Peterson is so popular and what it is about his message that has resonated with so many people,’’ says Amrani at the outset. So she attends a Peterson lecture, she speaks to a number of fellow attendees.

She listens. In eight and a half minutes, the open-minded viewer will learn far more about Peterson – and his message – than from any of the viral interviews conducted by more antagonistic journalists. The response was overwhelmingly positive. ‘Not a hit piece; a fair look. I’m legit shocked. Congrats.’ read a typical YouTube comment on the video.

Subsequent episodes have covered everything from male circumcision to the impact of pornography on male self-esteem to the struggles of fatherhood. Amrani has visited barbershops, football pitches, UFC 244. She has spoken to Love Island star Jack Fowler, newsreader Jon Snow, MMA fighter Jorge Masvidal and a host of men and women from every imaginable background.

The series is comfortably one of the best things being produced by the Guardian today but don’t take my word for it: Modern Masculinity was nominated for an RTS journalism award in 2020 and won People’s Choice at the Webby Awards this year.

No episode of Modern Masculinity is the same but their one constant is Amrani – her relentless curiosity, her lack of judgement, the ease with which she explores so many different spaces and personalities. In the Peterson episode, she says, “Truth always trumps political correctness with me, but you have to couple that with respect and listening to people.” It’s a mantra she never betrays.

One of her heroes is the late, great Anthony Bourdain. “Completely flawed character, 100%. Had a lot of issues. Didn’t handle everything in the best way possible. But the work he made was just very human. He wasn’t trying to be a celebrity, as it were. It wasn’t supposed to be totally glamorous. It was very much, ‘what is the point of it all?’ Meeting people, hearing their stories, understanding the details that make up our lives. I love that.”

View on Instagram

Like all of us, Amrani was shaped by her upbringing and heritage. She’s Algerian-British: mother from North Stockport, father from Oran. “Two different cultures, like oil and water to be honest with you. Growing up, that definitely helped me learn how to navigate different viewpoints and experiences at the same time. I became quite versatile in conversation and also world viewpoints.”

When young, “I was always wanting to be in interesting spaces.” Her upbringing was strict: Islamic school on Saturday, minimal contact with other kids. “I think I wanted to become a journalist because I really wanted to explore the world, I really wanted to get out and see what was going on that my friends got to do. To be honest, they were probably just breaking into the quarry and kissing boys.”

She has travelled a lot further than the quarry, and her career is still in relative infancy. What will the next few decades bring? More conversations, more adventure, more stories to be told. So much to learn and discover. One time in Santa Fe, Amrani was attempting to make conversation with some teenage sex workers. She asked if they listened to reggaeton. No, said the girls – it’s quite derogatory towards women.

Amrani laughs at the memory. “I had to reprogram all the preconceptions I had. I’m constantly amazed, even now when I go out and meet people, I’m always having to challenge my own preconceptions – and I think I’m not very judgemental.

“That’s the best thing about this job. You meet people and you go [she clicks her fingers], ‘I think I’m learning stuff!’ But you realise you never really know anything.”

What matters is you keep asking questions. “I’m not all one thing or another thing,” says Amrani towards the end of our conversation. She cites her two grandmothers.

Her late Algerian grandmother: “She couldn’t read. She was an amazing woman, she was such a maternal, soft, gentle lady who would cook and look after everybody.” Her British grandmother “worked really hard to get her independence. She’s travelled the world, is very forthright.

“I look at the two of them and I’m like, you’re both great in their own ways. There’s not a right way for either one of you to be. You can’t transfer one onto the other.

“There isn’t a right answer. You just need to try and understand people.”

For more of Amrani's work, see Iman Amrani